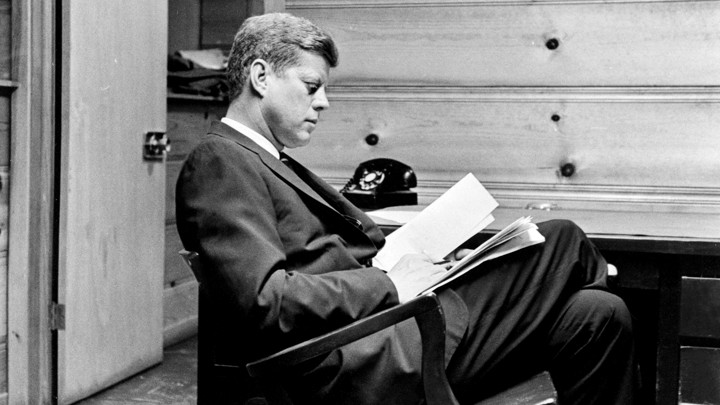

The Legacy of John F. Kennedy

among the many monuments to John F. Kennedy, perhaps the most striking is the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas, in the building that was once the Texas School Book Depository. Every year, nearly 350,000 people visit the place where Lee Harvey Oswald waited on November 22, 1963, to shoot at the president’s motorcade. The museum itself is an oddity because of its physical connection to the event it illuminates; the most memorable—and eeriest—moment of a visit to the sixth floor is when you turn a corner and face the window through which Oswald fired his rifle as Kennedy’s open car snaked through Dealey Plaza’s broad spaces below. The windows are cluttered once again with cardboard boxes, just as they had been on that sunny afternoon when Oswald hid there.

This article appears in the JFK issue.

Support 160 years of independent journalism. Starting at only $24.50. View more stories from the issue.

Visitors from all over the world have signed their names in the memory books, and many have written tributes: “Our greatest President.” “Oh how we miss him!” “The greatest man since Jesus Christ.” At least as many visitors write about the possible conspiracies that led to JFK’s assassination. The contradictory realities of Kennedy’s life don’t match his global reputation. But in the eyes of the world, this reticent man became a charismatic leader who, in his life and in his death, served as a symbol of purpose and hope.

President Kennedy spent less than three years in the White House. His first year was a disaster, as he himself acknowledged. The Bay of Pigs invasion of Communist Cuba was only the first in a series of failed efforts to undo Fidel Castro’s regime. His 1961 summit meeting in Vienna with the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was a humiliating experience. Most of his legislative proposals died on Capitol Hill.

Yet he was also responsible for some extraordinary accomplishments. The most important, and most famous, was his adept management of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, widely considered the most perilous moment since World War II. Most of his military advisers—and they were not alone—believed the United States should bomb the missile pads that the Soviet Union was stationing in Cuba. Kennedy, aware of the danger of escalating the crisis, instead ordered a blockade of Soviet ships. In the end, a peaceful agreement was reached. Afterward, both Kennedy and Khrushchev began to soften the relationship between Washington and Moscow.

Kennedy, during his short presidency, proposed many important steps forward. In an address at American University in 1963, he spoke kindly of the Soviet Union, thereby easing the Cold War. The following day, after almost two years of mostly avoiding the issue of civil rights, he delivered a speech of exceptional elegance, and launched a drive for a civil-rights bill that he hoped would end racial segregation. He also proposed a voting-rights bill and federal programs to provide health care to the elderly and the poor. Few of these proposals became law in his lifetime—a great disappointment to Kennedy, who was never very successful with Congress. But most of these bills became law after his death—in part because of his successor’s political skill, but also because they seemed like a monument to a martyred president.

Kennedy was the youngest man ever elected to the presidency, succeeding the man who, at the time, was the oldest. He symbolized—as he well realized—a new generation and its coming-of-age. He was the first president born in the 20th century, the first young veteran of World War II to reach the White House. John Hersey’s powerful account of Kennedy’s wartime bravery, published in The New Yorker in 1944, helped him launch his political career.

In shaping his legend, Kennedy’s personal charm helped. A witty and articulate speaker, he seemed built for the age of television. To watch him on film today is to be struck by the power of his presence and the wit and elegance of his oratory. His celebrated inaugural address was filled with phrases that seemed designed to be carved in stone, as many of them have been. Borrowing a motto from his prep-school days, putting your country in place of Choate, he exhorted Americans: “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

Another contributor to the Kennedy legend, something deeper than his personal attractiveness, is the image of what many came to call grace. He not only hadgrace, in the sense of performing and acting gracefully; he was also a man who seemed to receive grace. He was handsome and looked athletic. He was wealthy. He had a captivating wife and children, a photogenic family. A friend of his, the journalist Ben Bradlee, wrote a 1964 book about Kennedy called That Special Grace.

The Kennedys lit up the White House with writers, artists, and intellectuals: the famous cellist Pablo Casals, the poet Robert Frost, the French intellectual André Malraux. Kennedy had graduated from Harvard, and stocked his administration with the school’s professors. He sprinkled his public remarks with quotations from poets and philosophers.

The Kennedy family helped create his career and, later, his legacy. He could never have reached the presidency without his father’s help. Joseph Kennedy, one of the wealthiest and most ruthless men in America, had counted on his first son, Joe Jr., to enter politics. When Joe died in the war, his father’s ambitions turned to the next-oldest son. He paid for all of John’s—Jack’s—campaigns and used his millions to bring in supporters. He prevailed on his friend Arthur Krock, of The New York Times, to help Jack publish his first book, Why England Slept. Years later, when Kennedy wrote Profiles in Courage with the help of his aide Theodore Sorensen, Krock lobbied successfully for the book to win a Pulitzer Prize.

The Kennedy legacy has a darker side as well. Prior to his presidency, many of JFK’s political colleagues considered him merely a playboy whose wealthy father had bankrolled his campaigns. Many critics saw recklessness, impatience, impetuosity. Nigel Hamilton, the author of JFK: Reckless Youth, a generally admiring study of Kennedy’s early years, summed up after nearly 800 pages:

He had the brains, the courage, a shy charisma, good looks, idealism, money … Yet, as always, there was something missing—a certain depth or seriousness of purpose … Once the voters or the women were won, there was a certain vacuousness on Jack’s part, a failure to turn conquest into anything very meaningful or profound.

I. F. Stone, the distinguished liberal writer, observed in 1973: “By now he is simply an optical illusion.”

Kennedy’s image of youth and vitality is, to some degree, a myth. He spent much of his life in hospitals, battling a variety of ills. His ability to serve as president was itself a profile in courage.

Much has been written about Kennedy’s covert private life. Like his father, he was obsessed with the ritual of sexual conquest—before and during his marriage, before and during his presidency. While he was alive, the many women, the Secret Service agents, and the others who knew of his philandering kept it a secret. Still, now that the stories of his sexual activities are widely known, they have done little to tarnish his reputation.

half a century after his presidency, the endurance of Kennedy’s appeal is not simply the result of a crafted image and personal charm. It also reflects the historical moment in which he emerged. In the early 1960s, much of the American public was willing, even eager, to believe that he was the man who would “get the country moving again,” at a time when much of the country was ready to move. Action and dynamism were central to Kennedy’s appeal. During his 1960 presidential campaign, he kept sniping at the Republicans for eight years of stagnation: “I have premised my campaign for the presidency on the single assumption that the American people are uneasy at the present drift in our national course … and that they have the will and the strength to start the United States moving again.” As the historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Kennedy’s friend and adviser, later wrote, “The capital city, somnolent in the Eisenhower years, had suddenly come alive … [with] the release of energy which occurs when men with ideas have a chance to put them into practice.”

Kennedy helped give urgency to the idea of pursuing a national purpose—a great American mission. In the 15 years since World War II, ideological momentum had been slowly building in the United States, fueled by anxieties about the rivalry with the Soviet Union and by optimism about the dynamic performance of the American economy.

When Kennedy won the presidency, the desire for change was still tentative, as his agonizingly thin margin over Richard Nixon suggests. But it was growing, and Kennedy seized the moment to provide a mission—or at least he grasped the need for one—even though it was not entirely clear what the mission was. Early in his tenure, a Defense Department official wrote a policy paper that expressed a curious mix of urgent purpose and vague goals:

The United States needs a Grand Objective … We behave as if our real objective is to sit by our pools contemplating the spare tires around our middles … The key consideration is not that the Grand Objective be exactly right, it is that we have one and that we start moving toward it.

This reflected John Kennedy’s worldview, one of commitment, action, movement. Those who knew him realized, however, that he was more cautious than his speeches suggested.

john f. kennedy was a good president but not a great one, most scholars concur. A poll of historians in 1982 ranked him 13th out of the 36 presidents included in the survey. Thirteen such polls from 1982 to 2011 put him, on average, 12th. Richard Neustadt, the prominent presidential scholar, revered Kennedy during his lifetime and was revered by Kennedy in turn. Yet in the 1970s, he remarked: “He will be just a flicker, forever clouded by the record of his successors. I don’t think history will have much space for John Kennedy.”

But 50 years after his death, Kennedy is far from “just a flicker.” He remains a powerful symbol of a lost moment, of a soaring idealism and hopefulness that subsequent generations still try to recover. His allure—the romantic, almost mystic, associations his name evokes—not only survives but flourishes. The journalist and historian Theodore White, who was close to Kennedy, published a famous interview for Life magazine with Jackie Kennedy shortly after her husband’s assassination, in which she said:

At night, before we’d go to sleep, Jack liked to play some records; and the song he loved most came at the very end of this record. The lines he loved to hear were: Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot.

And thus a lyric became the lasting image of his presidency.

White, in his memoirs, recalled the reverence Kennedy had inspired among his friends:

I still have difficulty seeing John F. Kennedy clear. The image of him that comes back to me … is so clean and graceful—almost as if I can still see him skip up the steps of his airplane in that half lope, and then turn, flinging out his arm in farewell to the crowd, before disappearing inside. It was a ballet movement.

Friends were not the only ones enchanted by the Kennedy mystique. He was becoming a magnetic figure even during his presidency. By the middle of 1963, 59 percent of Americans surveyed claimed that they had voted for him in 1960, although only 49.7 percent of voters had actually done so. After his death, his landslide grew to 65 percent. In Gallup’s public-opinion polls, he consistently has the highest approval rating of any president since Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The circumstances of Kennedy’s death turned him into a national obsession. A vast number of books have been published about his assassination, most of them rejecting the Warren Commission’s conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. After the assassination, even Robert F. Kennedy, the president’s brother, spent hours—perhaps days—phoning people to ask whether there had been a conspiracy, until he realized that his inquiries could damage his own career. To this day, about 60 percent of Americans believe that Kennedy fell victim to a conspiracy.

“There was a heroic grandeur to John F. Kennedy’s administration that had nothing to do with the mists of Camelot,” David Talbot, the founder of Salon, wrote several years ago. His book Brothers: The Hidden History of the Kennedy Years, more serious than most Kennedy conspiracy theories, suggested that the president’s bold, progressive goals—and the dangers he posed to entrenched interests—inspired a plot to take his life.

There are many reasons to question the official version of Kennedy’s murder. But there is little concrete evidence to prove any of the theories—that the Mafia, the FBI, the CIA, or even Lyndon B. Johnson was involved. Some people say his death was a result of Washington’s covert efforts to kill Castro. For many Americans, it stretches credulity to accept that an event so epochal can be explained as the act of a still-mysterious loner.

Well before the public began feasting on conspiracy theories, Kennedy’s murder reached mythic proportions. In his 1965 book, A Thousand Days, Schlesinger used words so effusive that they seem unctuous today, though at the time they were not thought excessive or mawkish: “It was all gone now,” he wrote of the assassination: “the life-affirming, life-enhancing zest, the brilliance, the wit, the cool commitment, the steady purpose.”

Like all presidents, Kennedy had successes and failures. His administration was dominated by a remarkable number of problems and crises—in Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam; and in Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama. Some of these, he managed adroitly and, at times, courageously. Many, he could not resolve. He was a reserved, pragmatic man who almost never revealed passion.

Yet many people saw him—and still do—as an idealistic and, yes, passionate president who would have transformed the nation and the world, had he lived. His legacy has only grown in the 50 years since his death. That he still embodies a rare moment of public activism explains much of his continuing appeal: He reminds many Americans of an age when it was possible to believe that politics could speak to society’s moral yearnings and be harnessed to its highest aspirations. More than anything, perhaps, Kennedy reminds us of a time when the nation’s capacities looked limitless, when its future seemed unbounded, when Americans believed that they could solve hard problems and accomplish bold deeds.

No comments:

Post a Comment