What Is the Far Right’s Endgame? A Society That Suppresses the Majority.

Nancy MacLean, author of an intellectual biography of James McGill Buchanan, explains how this little-known libertarian’s work is influencing modern-day politics.

Photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo. Photos by MBisanz/Wikimedia, Dechateau/Wikimedia, Atlas Network/Wikimedia, and Thinkstock.

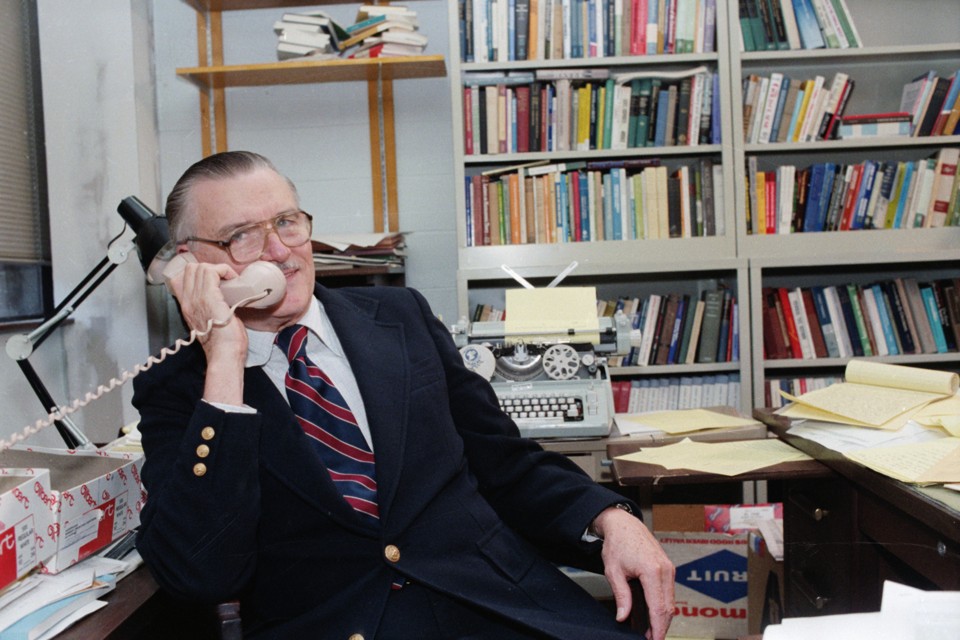

When the Supreme Court decided, in the 1954 case of Brown vs. Board of Education, that segregated public schools were unconstitutional, Tennessee-born economist James McGill Buchanan was horrified. Over the course of the next few decades, the libertarian thinker found comfortable homes at a series of research universities and spent his time articulating a new grand vision of American society, a country in which government would be close to nonexistent, and would have no obligation to provide education—or health care, or old-age support, or food, or housing—to anyone.

This radical vision has become theplaybook for a network of people looking to override democracy in order to shift more money to the wealthiest few, historian and professor at Duke University Nancy MacLean argues in her new book, an intellectual biography of James Buchanan called Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America.* Buchanan’s life story, she writes, is “the true origin story of today’s well-heeled radical right.”

I spoke with MacLean about Buchanan’s intellectual evolution and its legacy today. We discussed whether it’s helpful or counterproductive to call the network of organizations funded by Charles Koch a “conspiracy,” the line of influence between Buchanan and what’s going on in MacLean’s home state of North Carolina, and that time Buchanan helped Chile’s dictator craft a profoundly undemocratic constitution. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

So why is James Buchanan so unknown? He had a Nobel Prize; how did he manage to fly under the radar?

He had a very different personality from somebody like Milton Friedman. I think of them as kind of a yin and yang. Friedman was very sunny, and Buchanan was kind of a darker figure. Friedman was always very anxious to be in the limelight, and Buchanan was not like that at all. He was very interested in making an impact over the long term and training other people, and he seemed to be content to talk to powerful people more than to talk to public audiences. His books were really written for other scholars, not so much the general public.

Can you put him in relationship with other people, besides Friedman, who might be more familiar to us today?

People might be familiar with the Mont Pelerin Society, the international invitation-only group that began in 1947 launched by Friedrich Hayek. That society included Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Milton Friedman, Buchanan, ultimately Charles Koch (which I think not many people know!), and many others.

Friedman and Hayek put much more emphasis on making the case for free markets, whereas Buchanan’s distinctive mission was to make a case against government. … His basic idea is that people had been wrong to think of political actors as concerned with the common good or the public interest, when in fact, according to Buchanan’s way of looking at things, everyone should be understood as a self-interested actor seeking their own advantage. He said we should think of politicians, elected officials, as seeking their own self-interest in re-election. And that’s why they’ll make multiple costly promises to multiple constituencies, because they won’t have to pay for it. And he would say agency officials—say, an official at the EPA—would just keep trying to expand the agency, because that would expand their power and resources.

Now there were other people who actually tested that empirically and found out that it didn’t hold, so it’s really a caricature of the political process, but it’s a caricature that’s become very, very widespread right now.

You mentioned a few times in the book that Buchanan didn’t really do empirical research. So what was he writing from?

He was also trained in game theory at the Rand Corporation, so he uses a lot of that. But basically he writes more like a social philosopher, someone studying the social contract.

Did his ideas change over time?

The core ideas kind of stayed the same. What did change over time was his own outlook. It became much darker over the years. His first big book in his field, which is called public choice economics, was titled The Calculus of Consent, and it came out in 1962 and was co-authored with Gordon Tullock. It was the work for which Buchanan was most recognized in his Nobel citation. In that work, he seemed to believe that somehow people of good will could come to something close to unanimity on the basic rules of how to govern our society, on things like taxation and government spending and so forth.

And by the mid-1970s he concluded that that was impossible, and that there was no way that poor people would ever agree … there was no way that people who were not wealthy, who were not large property owners, would agree to the kind of rules he was proposing. So that was a very dark work. It was called The Limits of Liberty. He actually said in that work that the only hope might be despotism.

And he went from writing that to advising the Pinochet junta in Chile on how to craft their constitution. This document was later called a “constitution of locks and bolts,” [and was designed] to make it so that the majority couldn’t make its will felt in the political system, unless it was a huge supermajority.

So yeah, it’s pretty dark.

Tell me more about the relationship between Koch and Buchanan.

I think too many people on the left have really underestimated Koch’s intelligence and his drive, and also misunderstood his motives. There’s been brilliant work by journalists, really good digging on the money trail and the Koch operations, but much of that writing seems to assume that he is doing this just because it’s going to lower his tax bill or because he wants to evade regulations, personally. I think that really misgauges the man. He is deeply ideological and has been reading almost fanatically for a very long time. I see him as someone who’s quite messianic. He’s compared himself to Martin Luther and his effort being like the Protestant Reformation. When he invested in Buchanan’s center at George Mason University, he said he wanted to “unleash the kind of force that propelled Columbus.”

This is not someone who’s just trying to lower his tax bill. He wants to bring in a totally new vision of society and government, that’s different from anything that exists anywhere in the world or has existed because he is so certain that he is right. I think it’s more chilling because it doesn’t correspond to the ideas we have about politics.

Right, like he’s not trying to get a particular person elected. You mention several times Buchanan was very against that idea, that the point was to get a particular person elected. The point, for him, was to change the whole system.

Right. You asked how the two men connected. I only have the documentary trail that I found. But from what I found, I believe that they first came in contact or first began to work together about 1969 or 1970, and that was in the context of the campus upheaval against the war in Vietnam, and for black studies, and so forth. Buchanan wrote a book about the campus unrest that applied his particular school of thought to it. Koch had an operation called the Center for Independent Education, and that center took Buchanan’s book and turned it into a kind of pamphlet that could be circulated more broadly.

In 1970, Koch joined the Mont Pelerin Society. Once he got in, he began to advertise his many different organizations and efforts and try to recruit and get people to events and so forth, through Mont Pelerin. Buchanan helped with the founding of the Cato Institute and with various other intellectual enterprises that were close to Charles Koch’s heart, like this thing called the Institute for Humane Studies.

And then Koch funded Buchanan’s center, as well as other projects, at George Mason University. One of Buchanan’s ideas that Koch liked was the concept of making a flurry of changes all at once so that people have a hard time opposing them.

Yes, and in the same year that Koch invested all this money in George Mason, [economist] Tyler Cowen got a commission by the Institute for Humane Studies to produce this review of places where economic liberty has made big advances. Cowen advocates what he calls a “Big Bang.”

Interestingly it’s that same phrase that gets used by Civitas, the Koch-affiliated organization in North Carolina, after they take over the state legislature here in 2011. I actually have to give the North Carolina Republican-led General Assembly some credit for this book because I was struggling through Buchanan’s ideas, trying to understand the implications, because he did write in a somewhat abstract manner. And then the General Assembly came in in North Carolina and just made it all so clear. I saw the practical measures being taken and was like, “Oh, this is what he’s talking about! That’s what this is!” I should have put them in the acknowledgements.

I’d like to talk more about the way racism works in Buchanan’s intellectual project. You write in the conclusion to the book that this school of thought advocates “enlisting white supremacy to ensure capital supremacy.” Is it possible to disentangle those two?

So this is a challenge for the left because some of our categories, I think, are not very supple, and are also driven by the political world in which we operate. So for example, as we try to think about what’s going on with these voter suppression measures, the only thing that’s actionable is racial discrimination. Right? And so people think of voter suppression efforts as being motivated by racism. These are these good old boys who hate black people and that’s why they’re doing this.

I think actually what’s going on is that these people are extremely shrewd and calculating, and they understand that African Americans, because of their historical experience and their political savvy, understand politics and government better, in a lot of ways, than a lot of white Americans. And they are a threat to this project because they will not vote for it. So they want to keep them from the polls.

Similarly, young people are leaning left now, and they don’t accept a lot of these core ideas that come from this project, so this project has been very determined to keep young people from the polls. Frankly, if they could keep women away, they would, too. Because they understand that women suffrage opened the way to greater government involvement in the economy, and greater social provision and regulation.

We make a mistake when we think these are just reactionary prejudices, and we need to see them as shrewd calculations to keep people who would oppose this vision away from the polls.

So it’s about power, money.

Not just money. I think it’s also much more about this psychology of threatened domination. People who believe it will harm their liberty for other people to have full citizenship and be able to work together to govern society. And that somehow that goes much deeper than money to me. It’s hard to find the right words for it, but it’s a whole way of being in the world and seeing others. Assuming one’s right to dominate.

Your book calls Buchanan’s ideas a “stealth plan.” How can we, on the left, avoid falling into the trap of conspiracy-theory thinking while trying to understand this movement?

One of the challenges is that our language is not up to the threat that we’re facing. As a scholar, I understand the problem of conspiracy theories. I don’t want to be seen as promoting a conspiracy theory. Not least because this is not a conspiracy, by definition. A conspiracy involves illegality, and the people who are funding, and supporting and promoting this operation have extremely good lawyers and I think they actually do believe in the rule of law, and they are being, with the possible exemption of nonprofit tax law, scrupulously legal in what they are doing.

So conspiracy is not a good word. But on the other hand, this is a vast and interconnected and not honest operation. They say these anodyne things about liberty—like the title of one book is Don’t Hurt People And Don’t Take Their Stuff! And that’s not what this is about. The reality is that they are gerrymandering with a vengeance, to a degree we’ve never seen before in our history; they’re practicing voter suppression in a way we’ve not seen since Reconstruction; they are smashing up labor unions under fake pretenses, not telling people that they actually do want to destroy workers’ ability to organize collectively ... I could go on and on.

They’re doing a lot of things for strategic reasons and not being honest with the public about it. That suggests to me that we need a new vocabulary for grasping what we’re dealing with here. I guardedly used the term “fifth column” in the book, and you know, there’s problems with that term too, but at least it gets at the fact that these wealthy donors that Charles Koch has convened are deeply hostile to the model of government that has prevailed in the United States and in many other countries for a century.

While I think we need all the great investigative work that’s being done to try to show us how these organizations that are being presented to the public as separate are actually coordinating together, I don’t think that just laying that out is enough. I think that what we need to convey to people is that this is a messianic cause, with a vision of the good society and government that I think most of us would find terrifying, for the practical implications and impact that it will have on our lives.

We are at a crucial moment in our history, and we will not get another chance, by this cause’s own telling. They say again and again that this is going to be permanent, and they’re very close to victory. So I think we need to be really clear-eyed about understanding this and reaching out to one another without panic.

The most important thing I want readers to take from this book is an understanding that the Koch network and all of these people are doing what they’re doing because they understand that their ideas make them a permanent minority. They cannot win if they are honest about what they’re doing. That’s why they’re doing things in the deceitful and frightening ways that they are.

And that, I think, is a sign of great power for the majority of people, who I think are fundamentally decent, and agree on much more than we’re led to believe.

*Update, June 22, 2017: This article has been updated to add MacLean's academic credentials. (Return.)