The Architect of the Radical Right

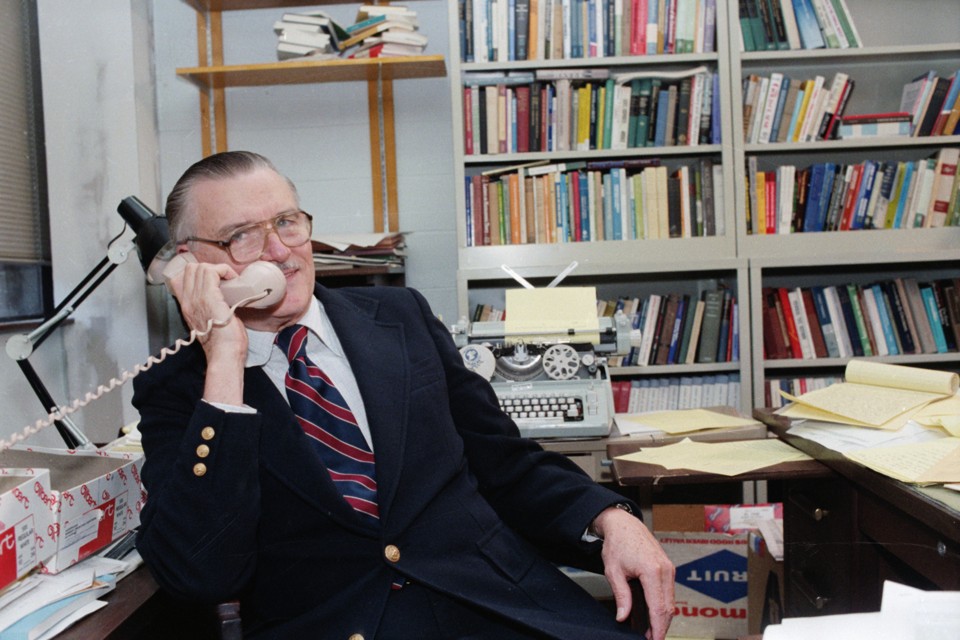

How the Nobel Prize–winning economist James M. Buchanan shaped today’s antigovernment politics

If you read the same newspapers and watch the same cable shows I do, you can be forgiven for not knowing that the most populous region in America, by far, is the South. Nearly four in 10 Americans live there, roughly 122 million people, by the latest official estimate. And the number is climbing. For that reason alone, the South deserves more attention than it seems to be getting in political discussion today.

But there is another reason: The South is the cradle of modern conservatism. This, too, may come as a surprise, so entrenched is the origin myth of the far-westerners Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan as leaders of a Sun Belt realignment and forerunners of today’s polarizing GOP. But each of those politicians had his own “southern strategy,” playing to white backlash against the civil-rights revolution—“hunting where the ducks are,” as Goldwater explained—though it was encrypted in the states’-rights ideology that has been vital to southern politics since the days of John C. Calhoun.Talmadge’s movement is a footnote now, but it boasted delegates from 18 states and offered an early mix of the populist grievance and anti-tax fervor that presaged Tea Party protests, though the original brew had a pungent tang of racism. At a rabble-rousing “grassroots convention” held in Macon, Georgia, delegates received a news sheet that showed a photo of Eleanor Roosevelt in the company of two Howard University ROTC students. Her husband, the caption warned, was permitting “negroes to come to the White House banquets and sleep in the White House beds.” What looked like a redneck eruption was in fact financed by northern capitalists nursing their own hatred of the New Deal. Talmadge’s promise to slash property taxes brought in big checks from the du Ponts, among others.

Why does all this matter today? Well, we might begin with the first New Yorker elected president since FDR, a man who has given new meaning to the term copperhead (originally applied to Northern Democrats who opposed the Civil War). Lost amid the many 2016 postmortems, and the careful parsing of returns in Ohio swing counties, was Donald Trump’s prodigious conquest of the South: 60 percent or more of the vote in Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and West Virginia, with similar margins in Louisiana and Mississippi. And the message is still being missed. We’ve heard much about the “older white men” in the administration, but rather less about where they come from. No fewer than 10 Cabinet appointees are from the South, in key positions like attorney general (Alabama) and secretary of state (Texas), not to mention Trump’s top political adviser, Steve Bannon, who grew up in Virginia.

All of this, so plainly in view but so strangely ignored, makes MacLean’s vibrant intellectual history of the radical right especially relevant. Her book includes familiar villains—principally the Koch brothers—and devotes many pages to think tanks like the Cato Institute and the Heritage Foundation, whose ideological programs are hardly a secret. But what sets Democracy in Chains apart is that it begins in the South, and emphasizes a genuinely original and very influential political thinker, the economist James M. Buchanan. He is not so well remembered today as his fellow Nobel laureates Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. Yet as MacLean convincingly shows, his effect on our politics is at least as great, in part because of the evangelical fervor he brought to spreading his ideas.It helped that Buchanan, despite his many accomplishments, continued to think of himself as an embattled outsider and also as a revolutionary. In 1973, well before the term counterestablishment was popularized, Buchanan was rallying like-minded allies to “create, support, and activate an effective counterintelligentsia” that could transform “the way people think about government.” Thirteen years later, when he won his Nobel Prize, he received the news as more than a validation of his work. His success represented a victory over the “Eastern academic elite,” achieved by someone who was, he said, “proud to be a member of the great unwashed.”

Buchanan owed his tenacity to blood and soil and upbringing. Born in 1919 on a family farm in Tennessee, he came of age during the Great Depression. His grandfather had been an unpopular governor of that state, and Buchanan grew up in an atmosphere of half-remembered glory and bitterness, without either money or useful connections. His exceptional mind was his visa into the academy and then into the world of big ideas. “Better than plowing,” which he made the title of his 1992 memoir, was advice he got from his first mentor, the economist Frank Knight at the University of Chicago, where Buchanan received his doctorate in 1948. During the postwar years, other faculty included Hayek and Friedman, who were shaping a new pro-market economics, part of a growing backlash against the policies of the New Deal. Hayek initiated Buchanan into the Mont Pelerin Society, the select group of intellectuals who convened periodically to talk and plot libertarian doctrine.

Today we remember ferocious civil-rights struggles waged in Birmingham and Selma. But ground zero for the respectable defense of Jim Crow was Virginia, where one of the nation’s most powerful politicians, Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr., ruled with the authority of an old-style feudal boss. His notorious “machine” kept the state clenched in an iron grip; the oppressions included a poll tax that suppressed black voter turnout so that it was on a par with the Deep South’s (and kept overall turnout under 20 percent). Byrd had allies in the president of the University of Virginia, Colgate Darden, and the newspaperman James Jackson Kilpatrick, who, long before his lovable-curmudgeon TV role on the “Point-Counterpoint” segment of 60 Minutes in the 1970s, was a fanatical and ingenious segregationist.

Far-fetched though these schemes were, they gave ammunition to southern policy makers looking to mount the nonracial case for maintaining Jim Crow in a new form. Friedman himself left race completely out of it. Buchanan did too at first, telling skeptical colleagues in the North that the “transcendent issue” had nothing to do with race; it came down to the question of “whether the federal government shall dictate the solutions.” But in their paper (initially a document submitted to a Virginia education commission and soon published in a Richmond newspaper), Buchanan and Nutter were more direct, stating their belief that “every individual should be free to associate with persons of his own choosing”—the sanitized phrasing of segregationists.

Either way, the proximate result of Buchanan’s privatizing scheme was to help prolong the stalemate in Virginia. In Prince Edward County, to cite the most egregious example, public schools were padlocked for a full five years. From 1959 to 1964, white children went to tax-subsidized private schools while most black children stayed home—roughly what some politicians had in mind all along. The episode was, among other things, a vivid early instance of the bait and switch, so familiar now, whereby many libertarians seem curiously indifferent to the human cost of their rigid principles, even as they denounce the despotism of all three branches of the federal government.

This idea turned the whole notion of a beneficent government, and of programs and policies designed more or less selflessly, into a kind of fairy tale expertly woven by politicians and their flacks. Not that politicians were evil. They were looking out for themselves, as most of us do. The difference was in the damage they did. After all, the high-priced programs they devised were paid for by taxes wrested from defenseless citizens, who were given little or no effective choice in the matter. It was licensed theft, reinforced by the steep gradations in income-tax rates.

Buchanan expertly maximized his own utility. Money was flowing into the Thomas Jefferson Center he established at the University of Virginia in 1957, enabling him to run it as an autonomous entity, with its own lecture series and fellowship programs. Free of oversight, Buchanan gathered disciples—he screened applicants according to ideology—and his semiprivate school of thought flourished. The obstacles lay in the body politic. The 1960s looked even worse than the ’50s. Not long after Buchanan’s big book was published, the War on Poverty began and then the Great Society—one lethal program after another.

Nixon called himself a Keynesian and committed a succession of sins, from creating government agencies (like the Environmental Protection Agency) to instituting wage and price controls. Meanwhile, the government kept expanding through entitlements and programs aimed at the middle class. You didn’t have to accept Buchanan’s ideology to see that he had a point about the growth of government-centered clientelism—“dependency,” in the term used by a new wave of neoconservatives such as Daniel Patrick Moynihan. For Buchanan, the trouble now went beyond the government. The enemy was the public itself, expressed through the tyranny of majority rule: The have-nots preyed on the rich, egged on by the new elite—labor bosses, benevolent corporations, and pandering politicians—who fell over themselves promising more and more.With Reagan, deliverance seemed possible. Buchanan’s political influence reached its zenith. By this time, he had left the University of Virginia. As early as 1963, there were concerns—on the part of the dean of the faculty, for one—that Buchananism, at least as practiced at his Thomas Jefferson Center, had petrified into dogma, with no room for dissenting voices. After a battle over a promotion for his co-author, Tullock, Buchanan left in a huff. He went first to UCLA, next to Virginia Tech, and in 1983, climactically, to George Mason University, not far outside the Beltway—and much nearer to the political action. The Wall Street Journal soon labeled George Mason “the Pentagon of conservative academia.” With its “stable of economists who have become an important resource for the Reagan administration,” it was now poised to undo Great Society programs. In 1986, Buchanan won the Nobel Prize for his public-choice theory.

But triumph gave way again to disappointment. Not even Reagan could stem the collectivist tide. Public-choice ideas made a difference—for instance in the balanced-budget act sponsored by Senators Philip Gramm, Warren Rudman, and Ernest Hollings in 1985. Buchanan’s theory found another useful ally in the budget-slasher and would-be government-shrinker David Stockman, who idolized Hayek and declared that “politicians were wrecking American capitalism.” But Stockman also discovered that restoring capitalism to a purer condition would mean declaring war on “Social Security recipients, veterans, farmers, educators, state and local officials, the housing industry.” What president was going to do that? Certainly not Reagan. As Stockman reflected, “The democracy had defeated the doctrine.”

At his death in 2013, Buchanan was hardly known outside the world of economists and libertarians, but his ideology remains much in force. His view of Social Security—a “Ponzi scheme”—is shared by privatizers like Paul Ryan. More broadly, Buchananism informs the conviction on the right that because the democratic majority can’t really be trusted, empowered minorities, like the Freedom Caucus, are the true guardians of our liberty and if necessary will resort to drastic measures: shutting down the government, defaulting on the national debt, and plying the techniques of what Francis Fukuyama calls our modern “vetocracy”—refusing, for example, to bring an immigration bill to a House vote lest it pass (as happened in the Obama years) or, in the Senate, defying tradition by not granting a confirmation hearing to a Supreme Court nominee.

With a researcher’s pride, MacLean confidently declares that Buchanan’s ideological journey, and the trail he left, contains the “true origin story of today’s well-heeled radical right.” Better to say that it is one story among many in the long narrative of conservative embattlement. The American right has always felt outnumbered, even in times of triumph. This is the source of both its strength and its weakness, just as it was for Buchanan, a faithful son of the South, with its legacy of defeats and lost causes. MacLean’s undisguised loathing of him and others she writes about will offend some readers. But that same intensity of feeling has inspired her to untangle important threads in American history—and to make us see how much of that history begins, and still lives, in the South.

No comments:

Post a Comment