PAST IS PROLOGUE?

Is America Doomed to Repeat Its Racist Past?

The minority that wants to hate has a passion however twisted, that most of the majority does not. And now they have the president of the country in their corner.

Each week of the Trump era brings some new, specific thing to be depressed about. One week it’s the future of the Constitution. Another it’s contemplating the shame of the United States starting a nuclear war. Another it’s something else.

In the wake of Charlottesville, it’s been race. More specifically, for me, the horror of the racial future that awaits us in both the short and longer terms. In the short term, it seems virtually certain that we’re in for another Charlottesville, and another, and another. It’s hard to think of any logical reason why the neo-Nazis wouldn’t march again; they got lots of publicity—not much of it positive, but as the old saw has it, they spelled their names right. And the president of the United States had their backs.

So one suspects that we’ll see more of these, and that the president will do what he has always done in cases like this and vacillate between reading a script with all the verve of a hostage and then saying and tweeting what he really thinks. It seems nearly impossible that it will dawn on him that as president he embodies the nation and should strive to represent both, or all, sides. He’s far too small-minded and insecure for that. And besides that, it’s increasingly hard to dispute the argument that this guy who does and says a lot of racist things is just plain racist, so he’s going to keep doing and saying racist things.

So that’s the short term. At the risk of tempting you to click away from this column and read something less morose, I have to say that right now, the long term for our country looks even worse.

If we look at our nation’s entire racial history, we see a pattern, and it’s not a reassuring one. I divide that history into six chapters.

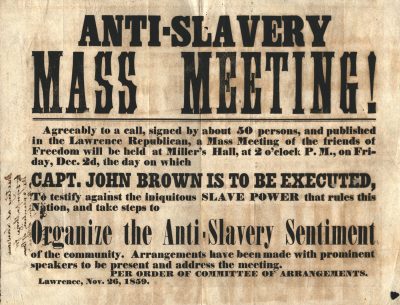

Chapter 1: Slavery. The original sin needed eight decades and a four-year war that killed 600,000 people to eradicate. The period was also characterized, we should remember, by monstrous political equivocation on the part of many people who knew better and a near-constant effort to placate the South and let it keep its peculiar institution. Anti-slavery but non-abolitionist Northern politicians decided from the Constitutional Convention onward that preserving the union was more important than doing anything about slavery. It was only after Stephen Douglas sold out the North and agreed to “popular sovereignty” for Kansas and Nebraska that everyone admitted what they (and their forebears) knew deep down all along—the slavery was immoral and unsustainable and inconsistent, to put it mildly, with the stated values of the republic.

Chapter 2: Emancipation. This was one of the great accomplishments in our history, and Abraham Lincoln will rightfully live on forever for doing it. It’s also worth remembering that it didn’t just happen. Ultimately it had to be done at gunpoint, during Reconstruction. But done it was.

Chapter 3: The Backlash. Emancipation was opposed immediately in the South, and yes, by a handful of “Copperheads” and “doughfaces” in the North, too. They couldn’t do much at first, with the Union Army occupying the South. But once the troops left in 1877, the backlash started in earnest, and you know that grim record: resegregation, Jim Crow, state constitutions in the South drawn up specifically to exclude blacks from political and civic life, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, and more.

We can say that the backlash lasted until the mid-1920s, culminating perhaps in that big Klan march on Washington in 1925, with 25,000 men in robes and hoods marching down Pennsylvania Avenue. It’s not as if there was no progress for African Americans in this time. Some African Americans came to national prominence like George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington, the NAACP was founded, the Harlem Renaissance began. But the point is that when black people were given a new level of freedom in Chapter 2, millions of white people rose up in Chapter 3 to resist and reverse it.

Chapter 4: The quiet status quo. The hallmark of this 30-year period from the 1920s to the 1950s was how little things changed in both South and North. In the South, we had apartheid. In the North, we didn’t quite have that, but we did have a society in which black people could expect to be hired for only a few categories of jobs and were, with a few exceptions, culturally invisible. The Daughters of the American Revolution wouldn’t even let a black woman sing at their hall until a sitting first lady basically made them (actually, the concert took place at the Lincoln Memorial). Harry Truman did integrate the armed forces, but that was about all that happened.

Chapter 5: The civil rights era. We might say this lasted until the mid- to late-1970s; yes, until Ronald Reagan. Funny, isn’t it, how the two periods of emancipation and a fuller equality for black people in this country were exactly 100 years apart.

Chapter 6: The post-civil rights era. This, too, has been an era of backlash against the progress. It’s more complicated than the first backlash, because in today’s America, black people have made tremendous advances. The vast majority of African Americans today are middle class (though net-worth racial disparities are massive). Black writers and entertainers are beloved by millions of whites in a way that wouldn’t have been possible before the civil rights revolution. America’s favorite physicist is a black man, and of course there’s Barack Obama.

But the backlash has been real and severe. On voting rights. In our public schools, which are now resegregated back to pre-1970s levels. In conservative rhetoric about the “moocher class,” in the anger that is constantly doused with gasoline by talk-radio hosts about the people who want something for nothing; and now in the streets of Charlottesville, egged on by the man we elected—we elected—to be the president.

I used to hope—used to think, actually—that the United States was on the cusp of turning a new page in race relations. I thought this back in the 1990s, when I noticed, for example, that Bob Dole didn’t play racial-resentment politics in his 1996 presidential run. I took that at the time as a more hopeful sign than I should have. I realized later that it was less a noble restraint than a lack of blunt racial instruments laying around. If Bill Clinton had vetoed the welfare bill, Dole would’ve been right there with the worst of them.

Then I thought Obama’s victory signaled something. No, not the “end of racism.” But I did think it mean that a majority of Americans was now ready for an uneasy racial truce. Not kumbaya time, but an acceptance of each other that was something a little better than grudging; an ability to sometimes agree—and more importantly, to sometimes disagree, but without making the disagreement racial.

Actually, I still think Obama’s victory signaled that about a majority of Americans. But what I didn’t reckon enough was that minority, which doesn’t want any part of a truce. They want to hate. They may have been a minority in 1789, and 1861, and 1956 when Rosa Parks rode on that bus. They are definitely a minority today. But they have a passion, however twisted, that most of the majority does not. And now they have the president of the country in their corner.

We’re not going anywhere on this, I’m afraid. We have a cycle of status quo, progress, and backlash, a cycle that has repeated itself twice in our 240-odd-year history. I once thought we were close to breaking that cycle. Now I fear we’re stuck in it. Is it really going to be the 2060s—that is, every 100 years—before we see important progress again? And are the 2080s fated to produce more backlash? I once thought we were better than that. But it may be precisely who we are.