A Matter of Facts

With much fanfare, The New York Times Magazine devoted an entire issue in August to what it called the 1619 Project. The project’s aim, the magazine announced, was to reinterpret the entirety of American history. “Our democracy’s founding ideals,” its lead essay proclaimed, “were false when they were written.” Our history as a nation rests on slavery and white supremacy, whose existence made a mockery of the Declaration of Independence’s “self-evident” truth that all men are created equal. Accordingly, the nation’s birth came not in 1776 but in 1619, the year, the project stated, when slavery arrived in Britain’s North American colonies. From then on, America’s politics, economics, and culture have stemmed from efforts to subjugate African Americans—first under slavery, then under Jim Crow, and then under the abiding racial injustices that mark our own time—as well as from the struggles, undertaken for the most part by black people alone, to end that subjugation and redeem American democracy.

The opportunity seized by the 1619 Project is as urgent as it is enormous. For more than two generations, historians have deepened and transformed the study of the centrality of slavery and race to American history and generated a wealth of facts and interpretations. Yet the subject, which connects the past to our current troubled times, remains too little understood by the general public. The 1619 Project proposed to fill that gap with its own interpretation.

To sustain its particular take on an immense subject while also informing a wide readership is a remarkably ambitious goal, imposing, among other responsibilities, a scrupulous regard for factual accuracy. Readers expect nothing less from The New York Times, the project’s sponsor, and they deserve nothing less from an effort as profound in its intentions as the 1619 Project. During the weeks and months after the 1619 Project first appeared, however, historians, publicly and privately, began expressing alarm over serious inaccuracies.

On December 20, the Times Magazine published a letter that I signed with four other historians—Victoria Bynum, James McPherson, James Oakes, and Gordon Wood. Our letter applauded the project’s stated aim to raise public awareness and understanding of slavery’s central importance in our history. Although the project is not a conventional work of history and cannot be judged as such, the letter intended to help ensure that its efforts did not come at the expense of basic accuracy. Offering practical support to that end, it pointed out specific statements that, if allowed to stand, would misinform the public and give ammunition to those who might be opposed to the mission of grappling with the legacy of slavery. The letter requested that the Times print corrections of the errors that had already appeared, and that it keep those errors from appearing in any future materials published with the Times’ imprimatur, including the school curricula the newspaper announced it was developing in conjunction with the project.

The letter has provoked considerable reaction, some of it from historians affirming our concerns about the 1619 Project’s inaccuracies, some from historians questioning our motives in pointing out those inaccuracies, and some from the Times itself. In the newspaper’s lengthy formal response, the New York Times Magazine editor in chief, Jake Silverstein, flatly denied that the project “contains significant factual errors” and said that our request for corrections was not “warranted.” Silverstein then offered new evidence to support claims that our letter had described as groundless. In the interest of historical accuracy, it is worth examining his denials and new claims in detail.

No effort to educate the public in order to advance social justice can afford to dispense with a respect for basic facts. In the long and continuing battle against oppression of every kind, an insistence on plain and accurate facts has been a powerful tool against propaganda that is widely accepted as truth. That tool is far too important to cede now.

My colleagues and i focused on the project’s discussion of three crucial subjects: the American Revolution, the Civil War, and the long history of resistance to racism from Jim Crow to the present. No effort to reframe American history can succeed if it fails to provide accurate accounts of these subjects.

The project’s lead essay, written by the Times staff writer Nikole Hannah-Jones, includes early on a discussion of the Revolution. Although that discussion is brief, its conclusions are central to the essay’s overarching contention that slavery and racism are the foundations of American history. The essay argues that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” That is a striking claim built on three false assertions.

“By 1776, Britain had grown deeply conflicted over its role in the barbaric institution that had reshaped the Western Hemisphere,” Hannah-Jones wrote. But apart from the activity of the pioneering abolitionist Granville Sharp, Britain was hardly conflicted at all in 1776 over its involvement in the slave system. Sharp played a key role in securing the 1772 Somerset v. Stewart ruling, which declared that chattel slavery was not recognized in English common law. That ruling did little, however, to reverse Britain’s devotion to human bondage, which lay almost entirely in its colonial slavery and its heavy involvement in the Atlantic slave trade. Nor did it generate a movement inside Britain in opposition to either slavery or the slave trade. As the historian Christopher Leslie Brown writes in his authoritative study of British abolitionism, Moral Capital, Sharp “worked tirelessly against the institution of slavery everywhere within the British Empire after 1772, but for many years in England he would stand nearly alone.” What Hannah-Jones described as a perceptible British threat to American slavery in 1776 in fact did not exist.

“In London, there were growing calls to abolish the slave trade,” Hannah-Jones continued. But the movement in London to abolish the slave trade formed only in 1787, largely inspired, as Brown demonstrates in great detail, by American antislavery opinion that had arisen in the 1760s and ’70s. There were no “growing calls” in London to abolish the trade as early as 1776.

“This would have upended the economy of the colonies, in both the North and the South,” Hannah-Jones wrote. But the colonists had themselves taken decisive steps to end the Atlantic slave trade from 1769 to 1774. During that time, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Rhode Island either outlawed the trade or imposed prohibitive duties on it. Measures to abolish the trade also won approval in Massachusetts, Delaware, New York, and Virginia, but were denied by royal officials. The colonials’ motives were not always humanitarian: Virginia, for example, had more enslaved black people than it needed to sustain its economy and saw the further importation of Africans as a threat to social order. But the Americans who attempted to end the trade did not believe that they were committing economic suicide.

Assertions that a primary reason the Revolution was fought was to protect slavery are as inaccurate as the assertions, still current, that southern secession and the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery. In his reply to our letter, though, Silverstein ignored the errors we had specified and then imputed to the essay a very different claim. In place of Hannah-Jones’s statement that “the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain … because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery,” Silverstein substituted “that uneasiness among slaveholders in the colonies about growing antislavery sentiment in Britain and increasing imperial regulation helped motivate the Revolution.” Silverstein makes a large concession here about the errors in Hannah-Jones’s essay without acknowledging that he has done so. There is a notable gap between the claim that the defense of slavery was a chief reason behind the colonists’ drive for independence and the claim that concerns about slavery among a particular group, the slaveholders, “helped motivate the Revolution.”

But even the evidence proffered in support of this more restricted claim—which implicitly cedes the problem with the original assertion—fails to hold up to scrutiny. Silverstein pointed to the Somerset case, in which, as I’ve noted, a British high court ruled that English common law did not support chattel slavery. Even though the decision did not legally threaten slavery in the colonies, Silverstein wrote, it caused a “sensation” when reported in colonial newspapers and “slavery joined other issues in helping to gradually drive apart the patriots and their colonial governments.”

In fact, the Somerset ruling caused no such sensation. In the entire slaveholding South, a total of six newspapers—one in Maryland, two in Virginia, and three in South Carolina—published only 15 reports about Somerset, virtually all of them very brief. Coverage was spotty: The two South Carolina newspapers that devoted the most space to the case didn’t even report its outcome. American newspaper readers learned far more about the doings of the queen of Denmark, George III’s sister Caroline, whom Danish rebels had charged with having an affair with the court physician and plotting the death of her husband. A pair of Boston newspapers gave the Somerset decision prominent play; otherwise, most of the coverage appeared in the tiny-font foreign dispatches placed on the second or third page of a four- or six-page issue.

Above all, the reportage was almost entirely matter-of-fact, betraying no fear of incipient tyranny. A London correspondent for one New York newspaper did predict, months in advance of the actual ruling, that the case “will occasion a greater ferment in America (particularly in the islands) than the Stamp Act,” but that forecast fell flat. Some recent studies have conjectured that the Somerset ruling must have intensely riled southern slaveholders, and word of the decision may well have encouraged enslaved Virginians about the prospects of their gaining freedom, which could have added to slaveholders’ constant fears of insurrection. Actual evidence, however, that the Somerset decision jolted the slaveholders into fearing an abolitionist Britain—let alone to the extent that it can be considered a leading impetus to declaring independence—is less than scant.

Slaveholders and their defenders in the West Indies, to be sure, were more exercised, producing a few proslavery pamphlets that strongly denounced the decision. Even so, as Trevor Burnard’s comprehensive study of Jamaica in the age of the American Revolution observes, “Somerset had less impact in the West Indies than might have been expected.” Which is not to say that the Somerset ruling had no effect at all in the British colonies, including those that would become the United States. In the South, it may have contributed, over time, to amplifying the slaveholders’ mistrust of overweening imperial power, although the mistrust dated back to the Stamp Act crisis in 1765. In the North, meanwhile, where newspaper coverage of Somerset was far more plentiful than in the South, the ruling’s principles became a reference point for antislavery lawyers and lawmakers, an important development in the history of early antislavery politics.

In addition to the Somerset ruling, Silverstein referred to a proclamation from 1775 by John Murray, the fourth earl of Dunmore and royal governor of Virginia, as further evidence that fears about British antislavery sentiment pushed the slaveholders to support independence. Unfortunately, his reference was inaccurate: Dunmore’s proclamation pointedly did not offer freedom “to any enslaved person who fled his plantation,” as Silverstein claimed. In declaring martial law in Virginia, the proclamation offered freedom only to those held by rebel slaveholders. Tory slaveholders could keep their enslaved people. This was a cold and calculated political move. The proclamation, far from fomenting an American rebellion, presumed a rebellion had already begun. Dunmore, himself an unapologetic slaveholder—he would end his career as the royal governor of the Bahamas, overseeing an attempt to establish a cotton slavery regime on the islands—aimed to alarm and disrupt the patriots, free their human property to bolster his army, and incite fears of a wider uprising by enslaved people. His proclamation was intended as an act of war, not a blow against the institution of slavery, and everyone understood it as such.

Dunmore’s proclamation (unlike the Somerset decision three years earlier) certainly touched off an intense panic among Virginia slaveholders, Tory and patriot alike, who were horror-struck that it might spark a general insurrection, as the groundbreaking historian Benjamin Quarles showed many years ago. To the hundreds of enslaved men, women, and children who escaped to Dunmore’s lines, the governor was unquestionably, as Richard Henry Lee disparagingly remarked, the “African hero.” To the 300 formerly enslaved black men who joined what the governor called Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment, outfitted with uniforms emblazoned with the slogan “Liberty to slaves,” he was a redeemer.

The spectacle likely stiffened the resolve for independence among the rebel patriots whom Dunmore singled out, but they were already rebels. The proclamation may conceivably have persuaded some Tory slaveholders to switch sides, or some who remained on the fence. It would have done so, however, because Dunmore, exploiting the Achilles’ heel of any slaveholding society, posed a direct and immediate threat to lives and property (which included, under Virginia law, enslaved persons), not because he affirmed slaveholders’ fears of “growing antislavery sentiment in Britain.” The offer of freedom in a single colony to persons enslaved by men who had already joined the patriots’ ranks—after a decade of mounting sentiment for independence, and after the American rebellion had commenced—cannot be held up as evidence that the slaveholder colonists wanted to separate from Britain to protect the institution of slavery.

To back up his argument that Dunmore’s proclamation, against the backdrop of a supposed British antislavery outpouring, was a catalyst for the Revolution, Silverstein seized upon a quotation not from a Virginian, but from a South Carolinian, Edward Rutledge, who was observing the events at a distance, from Philadelphia. “A member of South Carolina’s delegation to the Continental Congress wrote that this act did more to sever the ties between Britain and its colonies ‘than any other expedient which could possibly have been thought of,’” Silverstein wrote.

Although he would become the youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence, Rutledge, a hyper-cautious patriot, was torn, late in 1775, about whether the time was yet ripe to move forward with a formal separation from Britain. By early December, while serving his state in the Continental Congress, he had moved toward finally declaring independence, in response to various events that had expanded the Americans’ rebellion, including the American invasion of Canada; news of George III’s refusal to consider the Continental Congress’s petition for reconciliation; the British burning of the town of Falmouth, Maine; and, most recently, Dunmore’s proclamation, full news of which was only just reaching Philadelphia.

In a private letter explaining his evolving thoughts, Rutledge described the proclamation as “tending in my judgment, more effectively to work an eternal separation” between Britain and America “than any other expedient which could possibly have been thought of.” By quoting only the second half of that statement, Silverstein altered its meaning, turning Rutledge’s personal and speculative observation into conclusive proof of a sweeping claim.

This is not the only flaw in Silverstein’s discussion. He seems unaware that, in the end, Rutledge himself was not sufficiently moved by Dunmore’s proclamation to support independence, and he rather notoriously led the opposition inside the Congress before switching at the last minute on July 1, 1776. Moreover, a man whom John Adams had earlier described as “a Swallow—a Sparrow—a Peacock; excessively vain, excessively weak, and excessively variable and unsteady—jejune, inane, & puerile” may not be the most reliable source.

To buttress his case, Silverstein also quoted the historian Jill Lepore: “Not the taxes and the tea, not the shots at Lexington and Concord, not the siege of Boston: rather, it was this act, Dunmore’s offer of freedom to slaves, that tipped the scales in favor of American independence.” But Silverstein’s claim about Dunmore’s proclamation and the coming of independence is no more convincing when it turns up, almost identically, in a book by a distinguished authority; Lepore also relies on a foreshortened version of the Rutledge quote, presenting it as evidence of what the proclamation actually did, rather than as one man’s expectation as to what it would do. As for Silverstein’s main contention, meanwhile, neither Lepore nor Rutledge said anything about the colonists’ fear of growing antislavery sentiment in Britain.

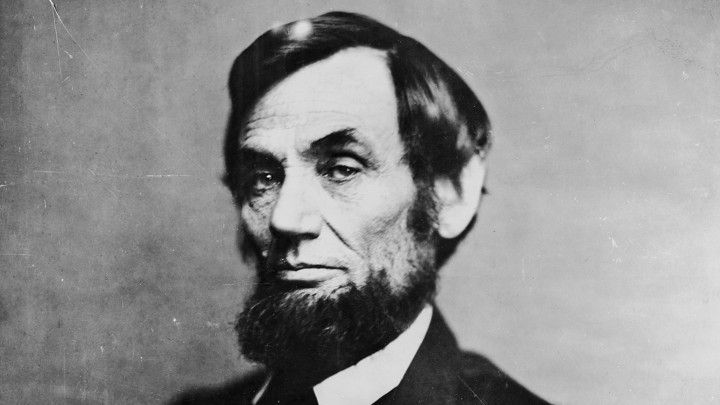

Only the civil war surpasses the Revolution in its importance to American history with respect to slavery and racism. Yet here again, particularly with regard to the ideas and actions of Abraham Lincoln, Hannah-Jones’s argument is built on partial truths and misstatements of the facts, which combine to impart a fundamentally misleading impression.

The essay chooses to examine Lincoln within the context of a meeting he called at the White House with five prominent black men from Washington, D.C., in August 1862, during which Lincoln told the visitors of his long-held support for the colonization of free black people, encouraging them voluntarily to participate in a tentative experimental colony. Hannah-Jones wrote that this meeting was “one of the few times that black people had ever been invited to the White House as guests”; in fact, it was the first such occasion. The essay says that Lincoln “was weighing a proclamation that threatened to emancipate all enslaved people in the states that had seceded from the Union,” but that he “worried about what the consequences of this radical step would be,” because he “believed that free black people were a ‘troublesome presence’ incompatible with a democracy intended only for white people.”

In fact, Lincoln had already decided a month earlier to issue a preliminary version of the Emancipation Proclamation with no contingency of colonization, and was only awaiting a military victory, which came in September at Antietam. And Lincoln had supported and signed the act that emancipated the slaves in D.C. in June, again with no imperative of colonization—the consummation of his emancipation proposal from 1849, when he was a member of the House of Representatives.

Not only was Lincoln’s support for emancipation not contingent on colonization, but his pessimism was echoed by some black abolitionists who enthusiastically endorsed black colonization, including the early pan-Africanist Martin Delany (favorably quoted elsewhere by Hannah-Jones) and the well-known minister Henry Highland Garnet, as well as, for a time, Frederick Douglass’s sons Lewis and Charles Douglass. And Lincoln’s views on colonization were evolving. Soon enough, as his secretary, John Hay, put it, Lincoln “sloughed off” the idea of colonization, which Hay called a “hideous & barbarous humbug.”

But this Lincoln is not visible in Hannah-Jones’s essay. “Like many white Americans,” she wrote, Lincoln “opposed slavery as a cruel system at odds with American ideals, but he also opposed black equality.” This elides the crucial difference between Lincoln and the white supremacists who opposed him. Lincoln asserted on many occasions, most notably during his famous debates with the racist Stephen A. Douglas in 1858, that the Declaration of Independence’s famous precept that “all men are created equal” was a human universal that applied to black people as well as white people. Like the majority of white Americans of his time, including many radical abolitionists, Lincoln harbored the belief that white people were socially superior to black people. He insisted, however, that “in the right to eat the bread without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, [the Negro] is my equal, and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every other man.” To state flatly, as Hannah-Jones’s essay does, that Lincoln “opposed black equality” is to deny the very basis of his opposition to slavery.

Nor was Lincoln, who had close relations with the free black people of Springfield, Illinois, and represented a number of them as clients, known to treat black people as inferior. After meeting with Lincoln at the White House, Sojourner Truth, the black abolitionist, said that he “showed as much respect and kindness to the coloured persons present as to the white,” and that she “never was treated by any one with more kindness and cordiality” than “by that great and good man.” In his first meeting with Lincoln, Frederick Douglass wrote, the president greeted him “just as you have seen one gentleman receive another, with a hand and voice well-balanced between a kind cordiality and a respectful reserve.” Lincoln addressed him as “Mr. Douglass” as he encouraged his visitor to spread word in the South of the Emancipation Proclamation and to help recruit and organize black troops. Perhaps this is why in his response, instead of repeating the claim that Lincoln “opposed black equality,” Silverstein asserted that Lincoln “was ambivalent about full black citizenship.”

Did Lincoln believe that free black people were a “troublesome presence”? That phrase comes from an 1852 eulogy he delivered in honor of Henry Clay, describing Clay’s views of colonization and free black people. Lincoln did not use those words in his 1862 meeting or on any occasion other than the eulogy. And Lincoln did not believe that the United States was “a democracy intended only for white people.” On the contrary, in his stern opposition to the Supreme Court’s racist Dred Scott v. Sandford decision in 1857, he made a point of noting that, at the time the Constitution was ratified, five of the 13 states gave free black men the right to vote, a fact that helped explode Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s contention that black people had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

To be sure, on this subject as on many others, one could easily cherry-pick isolated episodes from Lincoln’s long career to portray him very differently. As a first-term Illinois state legislator, in a display of party loyalty, Lincoln voted in favor of a sham, highly partisan Whig resolution against black suffrage in the state, introduced as a campaign gambit before the 1836 election against the Democrats who had enacted a restrictive black code. More than 20 years later, in 1859, fending off racist demagogy about his antislavery politics, he carefully denied a charge that he was proposing to give voting rights to black men, while still upholding black people’s human rights. But Lincoln fully recognized the political inclusion of free black people in several states at the nation’s founding, and he lamented how most of those states had either abridged or rescinded black voting rights in the intervening decades. Far from agreeing with Taney and others that American democracy was intended to be for white people only, Lincoln rejected the claim, citing simple and unimpeachable facts.

As president, moreover, Lincoln acted on his beliefs, taking enormous political and, as it turned out, personal risks. In March 1864, as he approached a difficult reelection campaign, Lincoln asked the Union war governor of Louisiana to establish the beginning of black suffrage in a new state constitution, “to keep the jewel of liberty within the family of freedom.” A year later, in his final speech, Lincoln publicly broached the subject of enlarging black enfranchisement, which was the final incitement to a member of the crowd, John Wilkes Booth, to assassinate him.

Silverstein acknowledged that Hannah-Jones’s essay presented a partial account of Lincoln’s ideas about abolition and racial equality, but excused the imbalance because the essay covered so much ground. “Admittedly, in an essay that covered several centuries and ranged from the personal to the historical, she did not set out to explore in full his continually shifting ideas about abolition and the rights of black Americans,” he wrote. In fact, throughout the essay’s lengthy discussion of Lincoln and colonization, what Silverstein called Lincoln’s “attitudes” are frozen in time, remote from political difficulties. Still, Silverstein contended, Hannah-Jones’s essay “provides an important historical lesson by simply reminding the public, which tends to view Lincoln as a saint, that for much of his career, he believed that a necessary prerequisite for freedom would be a plan to encourage the four million formerly enslaved people to leave the country.” Whether or not the public still regards Lincoln as a saint, a myth cannot be corrected by a distorted view. As Silverstein himself acknowledged, “At the end of his life, Lincoln’s racial outlook had evolved considerably in the direction of real equality.”

Moving beyond the civil war, the essay briefly examined the history of Reconstruction, the long and bleak period of Jim Crow, and the resistance that led to the rise of the modern civil-rights movement. “For the most part,” Hannah-Jones wrote, “black Americans fought back alone.”

This is the third claim that my colleagues and I criticized, and although it covers the longest period of the three, it can be dealt with most directly. Before, during, and after the Civil War, some white people were always an integral part of the fight for racial equality. From lethal assaults on white southern “scalawags” for opposing white supremacy during Reconstruction through resistance to segregation led by the biracial NAACP through the murders of civil-rights workers, white and black, during the Freedom Summer, in 1964, and in Selma, Alabama, a year later, liberal and radical white people have stood up for racial equality. A. Philip Randolph, the founder of the modern civil-rights movement, stated in his speech at the March on Washington, in 1963, “This civil-rights revolution is not confined to the Negro, nor is it confined to civil rights, for our white allies know that they cannot be free while we are not.”

Silverstein, in his reply, observed that civil-rights advances “have almost always come as a result of political and social struggles in which African-Americans have generally taken the lead.” But when it comes to African Americans’ struggles for their own freedom and civil rights, this is not what Hannah-Jones’s essay asserted.

The specific criticisms of the 1619 Project that my colleagues and I raised in our letter, and the dispute that has ensued, are not about historical trajectories or the intractability of racism or anything other than the facts—the errors contained in the 1619 Project as well as, now, the errors in Silverstein’s response to our letter. We wholeheartedly support the stated goal to educate widely on slavery and its long-term consequences. Our letter attempted to advance that goal, one that, no matter how the history is interpreted and related, cannot be forwarded through falsehoods, distortions, and significant omissions. Allowing these shortcomings to stand uncorrected would only make it easier for critics hostile to the overarching mission to malign it for their own ideological and partisan purposes, as some had already begun to do well before we wrote our letter.

Taking care of the facts is, I believe, all the more important in light of current political realities. The New York Times has taken a lead in combatting the degradation of truth and assault on a free press propagated by Donald Trump’s White House, aided and abetted by Vladimir Putin’s Russia, and spun by the far right on social media. American democracy is in a perilous condition, and the Times can report on that danger only by upholding its standards “without fear or favor.” That is why it is so important that lapses such as those pointed out in our letter receive attention and timely correction. When describing history, more is at stake than the past.

No historian better expressed this point, as part of the broader imperative for factual historical accuracy, than W. E. B. Du Bois. In Black Reconstruction in America, published in 1935, Du Bois challenged a reigning school of American historians working under the tutelage and guidance of William Archibald Dunning of Columbia University. The Dunning School, coupled with a broader current of Lost Cause defenders, produced works that characterized Reconstruction as vicious and vindictive, imposing the rule of corrupt and ignorant black people on a stricken postwar South. Those works, Du Bois understood, helped perpetuate racial oppression. Part of the genius of Black Reconstruction in America lay in Du Bois’s ability to mount a commanding counterinterpretation built on basic facts that the Dunning School had ignored or suppressed about the experiment in democratic government during Reconstruction and how it was overthrown and eventually replaced with Jim Crow.

In exposing the falsehoods of his racist adversaries, Du Bois became the upholder of plain, provable fact against what he saw as the Dunning School’s propagandistic story line. Du Bois repeatedly pointed out the “deliberate contradiction of plain facts.” Time and again in Black Reconstruction, he appealed to the facts against one or another false interpretation: “the plain, authentic facts of our history … perfectly clear and authenticated facts … the very cogency of my facts … the whole body of facts … certain quite well-known facts that are irreconcilable with this theory of history.” Only by carefully marshaling the facts was Du Bois able to establish the truth about Reconstruction. Indifference to the facts or their sloppy deployment, he argued, could lead and had led even intelligent scholars into “wide error.” Du Bois’s lesson should not be lost.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

SEAN WILENTZ teaches history at Princeton and is the author, most recently, of No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding.

No comments:

Post a Comment