How to Avoid Despair

Well, it’s over.

On February 6, 2020, the Senate acquitted Donald Trump on two articles of impeachment, bringing an end to a process the president has been hurtling toward since the moment of his inauguration. The case against him turned on the specifics of his efforts to pressure Ukraine to provide negative information on Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden. But in another sense, this impeachment had been inevitable since Trump swore the oath of office. He and the Constitution are irrevocably at odds; one way or another, the country was always going to end up here.

But “here” doesn’t just mean a world in which Trump has been impeached, of course; it’s also a world in which a majority of the Senate voted to bless his conduct. “Here,” then, is somewhere after the end of the story. The project now for safeguarding democracy in America is to figure out how to live in this post-acquittal era without giving in to hopelessness.

The two other presidents who faced impeachment in living memory both delivered natural ends to the drama. Richard Nixon’s helicopter lifted off the White House lawn after he resigned the presidency. Bill Clinton, the day of his acquittal in the Senate, stood in the Rose Garden and apologized for his conduct.

Not so Donald Trump. The day after the Senate vote, he gave a rambling speech in which he insisted that he had done nothing wrong, that the Russia investigation had been “bullshit,” and that his political opponents are “evil and sick.” He waved newspapers that read “Trump Acquitted.” His approval ratings have risen. Meanwhile, his Republican allies in the Senate are pushing forward with an investigation into Hunter Biden—exactly the subject on which Trump demanded dirt from Ukraine. The president did indeed learn a lesson (though not the one Maine Senator Susan Collins suggested)—he learned that he is for all intents and purposes immune to oversight and criticism, that he can do whatever he wants and get away with it.

Impeachment was always a Democratic pipe dream, a doomed act of idealism destined to be squelched in the Senate. This was also its power: an assertion of constitutional value in the face of nihilism. This came through clearly in lead House impeachment manager Adam Schiff’s closing argument for the House’s case, which ended with an appeal to justice. “I do not ask you to convict him because truth or right or decency matters nothing to him,” he said, “but because we have proven our case and it matters to you.” The Senate’s response, in acquitting, was clear: Nothing mattered.

The trouble with doomed acts of idealism, of course, is that they’re doomed. If the country has any luck, the impeachment of Donald Trump will be seen in the long term as the right thing to have done. In the meantime, though, we all have to live in the short term.

The temptation at this point is to give up and accept the president’s belief that he will be able to get away with anything. And indeed, much of the press coverage of the acquittal and Trump’s promises of vengeance amounted to a shrug: Well, what can you do, really? “Until the voters render their verdict, in November,” Susan Glasser wrote in The New Yorker, “Trump will be the President he has always wanted to be: inescapable, all-powerful, and completely unaccountable.” The New York Times described how “the self-described counterpuncher appears eager to prosecute his case against his prosecutors … Conciliation and acknowledging mistakes are not in his nature.” Perhaps a Washington Post headline best captured the sense of deflation: “Yeah, Trump didn’t learn any new lessons from impeachment.”

An exhausted shrug is a fair response to the bleakness of everything that has taken place over the three years of the Trump presidency, and especially to a week like this one. There is always a feeling of loss in the wake of a failure. The compelling way forward is to accept the inevitability that there will be other failures and keep pushing anyway.

Grappling with how to be in the world in this moment, I turned to the German sociologist Max Weber’s classic 1919 lecture “Politics as a Vocation,” which describes political life as torn between the voice of conscience and the practicalities of getting things done in an “ethically irrational” world. At a certain point, Weber wrote, a moment of crisis arrives: The irrationality becomes too much. The politician “reaches the point where he says: ‘Here I stand; I can do no other.’”

What moves Weber’s argument beyond a simple exploration of moral trade-offs in politics is his insistence that this moment of taking a stand, and the balancing act that it resolves, is both foundational to the human experience and deeply rare. Politics on these terms requires both principles and an insistence on engaging with a world that often doesn’t have space for them. This is hard work. And for many people it is not possible. But when it does occur, Weber wrote, it is something “genuinely human and moving.” It’s both the minimum requirement for moral engagement in political life and the clearest expression of what it means to be a person in a hard world. The lecture is not cheerful; Weber closed by warning his audience that “not summer's bloom lies ahead of us, but rather a polar night of icy darkness and hardness.”

There is wisdom in here for our present situation. The country has a long slog ahead of it; how long, nobody knows. It is easy to be cynical. But surviving the slog, without stepping away from it and bowing to the idea that nothing matters, is the only way to live through the short term. The frustrations resulting from failed or incomplete efforts to prevent wrongdoing are also part of that task. This doesn’t mean they’re necessary hurdles to be surmounted on the way to an inevitable victory; there’s no such thing. It’s just that this labor is, as Weber put it, what it means to have “measured up to the world.”

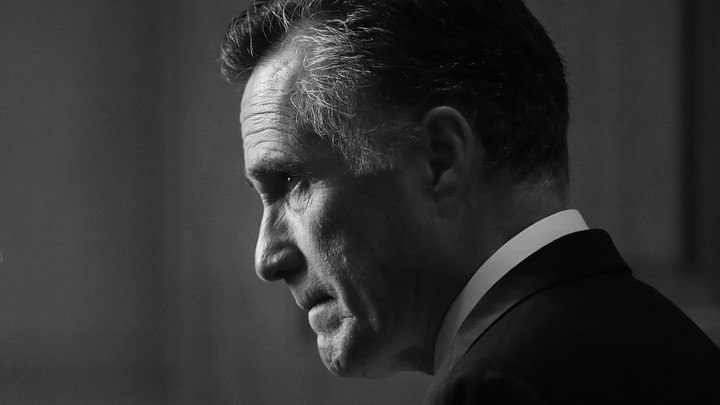

This is true for political leaders just as much as it is for everyday participants in civic life. As strange as it is to point to Republican Senator Mitt Romney—often lambasted for apparent political opportunism—as a model of conviction, his announcement that he would vote to convict the president of abuse of power seemed to cut through the haze of cynicism. “Were I to ignore the evidence that has been presented,” Romney argued, “and disregard what I believe my oath and the Constitution demands of me for the sake of a partisan end, it would, I fear, expose my character to history’s rebuke and the censure of my own conscience.” He was expressing a belief in the value of oath, history, and conscience that is at odds with the moral emptiness of both the president and many members of Romney’s party. At one point, speaking about his religious faith, he seemed to choke up. After Romney finished, Democratic Senator Brian Schatz left the Senate floor in tears.

Romney’s vote was a genuine act of bravery. It was also the bare minimum for any senator with a shred of principle. This doesn’t erase the courage it took; the nature of moral life is that we are often asked to do things that are beyond us.

Going forward, this work of measuring up to the world looks like the House continuing to investigate Trump along every axis of his misconduct. It looks like subpoenaing John Bolton and taking every measure to force him to testify before the House about what he saw the president do to pressure Ukraine. It looks like refusing to accept efforts by the president’s allies to investigate Hunter Biden, and like thwarting the president’s continued work to distort the fairness of the 2020 election.

It also looks like understanding that the locus of politics lies not only in Congress and the presidency but also outside it. This will mean thinking seriously about how to rebuild after Trump leaves office, and how to create a political life that exists outside him and is not dependent on him as its source of terrible gravity.

People across the country have been doing this work all along, of course. It hasn’t been more or less important than the impeachment process but was a necessary complement to it. Now that the president has been acquitted, it’s the only thing there is.

Weber’s vision of “genuinely human” engagement with politics is all the more resonant now because of how inhuman the president’s way of being is, and how uncomprehending of a world that has other people in it. As Schiff told the Senate in urging it to reject Trump’s actions, “He is not who you are.” Schiff turned out to be wrong, in this case at least, but his insistence is worth something nonetheless. Or to quote Weber: “When this night shall have slowly receded … what will have become of all of you by then?”

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment