Reclaiming Southern Pride

I moved from Houston, Texas, to Morristown, Tennessee, when I was 13 years old. Not long after, I had my first serious run-in with the Confederate flag. A high-school classmate of mine was wearing a T-shirt that bore it and some arrangement of the words “rebel” and “pride.” When I asked why he wore the shirt, ready to snap back against whatever racist response he might conjure up, he simply said it’s about Southern pride. For a long time, I almost bought it.

I’ve always carried with me a certain brand of Southern pride. There are few views more beautiful than the sun rising over the foothills of the Smoky Mountains. I appreciate the cordiality of strangers—when it’s genuine. And, yes, everything is bigger in Texas. I willingly identify with that unspoken bond that unites those of us born in the states of the South. But my brand of pride has never embraced the Confederate flag.

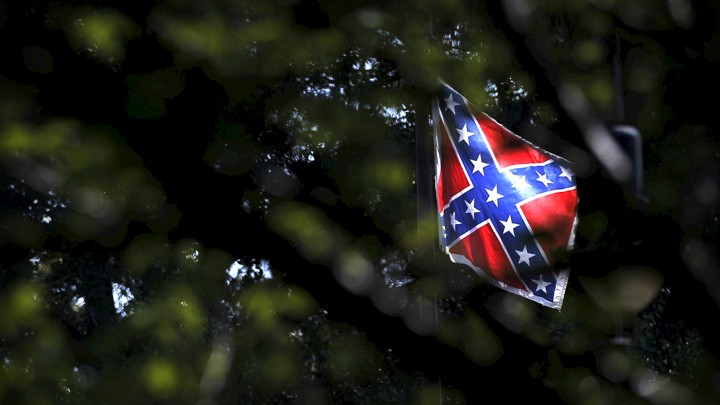

My dad told me last week that I’d be offended if I were to return home to Tennessee. Since the Confederate flag was removed from state capitol grounds in South Carolina, he explained, it has proliferated on lawns, bumper stickers, and T-shirts—it’s everywhere. “You wouldn’t believe it now.”

That flag simply cannot be divorced from the white-supremacist, pro-slavery doctrine of the Confederacy. My colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates made that case quite forcefully in his call to remove the flag in the wake of the attack on Emmanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston:

Visitors to Charleston have long been treated to South Carolina’s attempt to clean its history and depict its secession as something other than a war to guarantee the enslavement of the majority of its residents. This notion is belied by any serious interrogation of the Civil War and the primary documents of its instigators. Yet the Confederate battle flag—the flag of Dylann Roof—still flies on the Capitol grounds in Columbia.

And even post-Charleston, a majority—58 percent—of people living in the South consider it to be a symbol of pride. Among my Southern peers, in other words, my brand of pride is in the minority.

So I am unsurprised that the removal of the Confederate flag from South Carolina capitol grounds has been cause for many southerners to brandish their support for it. During critical moments of reform, people clinging to imperiled ideologies find ways to fight back. Take the anti-suffragists who battled against the Nineteenth Amendment long after the first women in the U.S. cast their ballots, for instance, or the presidential candidates today denouncing the Supreme Court’s ruling in favor of same-sex marriage.

Ironically, the Confederate flag owes its political resurrection to this sort of backlash—not in the immediate years after the war, not even a few decades after the war, but in the mid-20th century. Desegregation brought it out of closets and museums, revived as a symbol of white supremacy (the ideology of the Confederacy) and segregation. So while it sounds nice to claim that the flag is really only about honoring ancestors who fought valiantly during the Civil War, or that the flag represents the unmatched heartbreak and camaraderie that losing elicited among the citizens of the rebel states, any serious examination of history simply doesn’t back that up.

This history has been lost—or is simply ignored—by a number of southerners who say they don’t sport the flag with the subjugation of black people in mind. They insist it is about Southern pride. Perhaps to them, that is indeed all it’s about. The other “stuff” doesn’t matter anymore, and when people attack the flag, they attack their heritage. That is why the commissioner of a town that neighbors mine claims he is pushing for the flag to be flown over the city courthouse.

But it is the Confederate flag supporters who still embrace the doctrine of white supremacy who have the history right. And acts of racial intimidation, like the one that a group of Georgians are facing gang-related charges for this week, fit the history far better than claims about heritage. Yet there is little to distinguish their malice from others’ ignorance. And that matters because the consequences of that malice have manifested over the years in the form blatant discrimination, racial profiling, and the mass incarceration of black people. The Southern solidarity that the flag purportedly represents is not real; those who brandish it can’t even agree on its essence. It does more to divide the region than to unite it. And it’s certainly not a symbol of the South that I know today.

It was in the South that I was taught to appreciate the small things in life, and to love family and friends. It was in the South that I first saw firsthand the value in understanding different people and ideas, and in challenging my preconceptions. Real people—real southerners—are defined by these values every day. Yet they’re unlikely to be what comes to mind when non-southerners think about “the South.” The infatuation with the Confederate flag likely has some role in that.

Symbols matter, but the South as a region is far too nuanced to be fittingly represented by a Civil War battle flag with a contentious history. Southerners who agree have a responsibility to move into a new era, and to reclaim “Southern pride.” Because if the Confederate flag is my only means of displaying my Southern pride, then the South has already lost me.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

TYLER BISHOP is a former editorial fellow at The Atlantic.

No comments:

Post a Comment