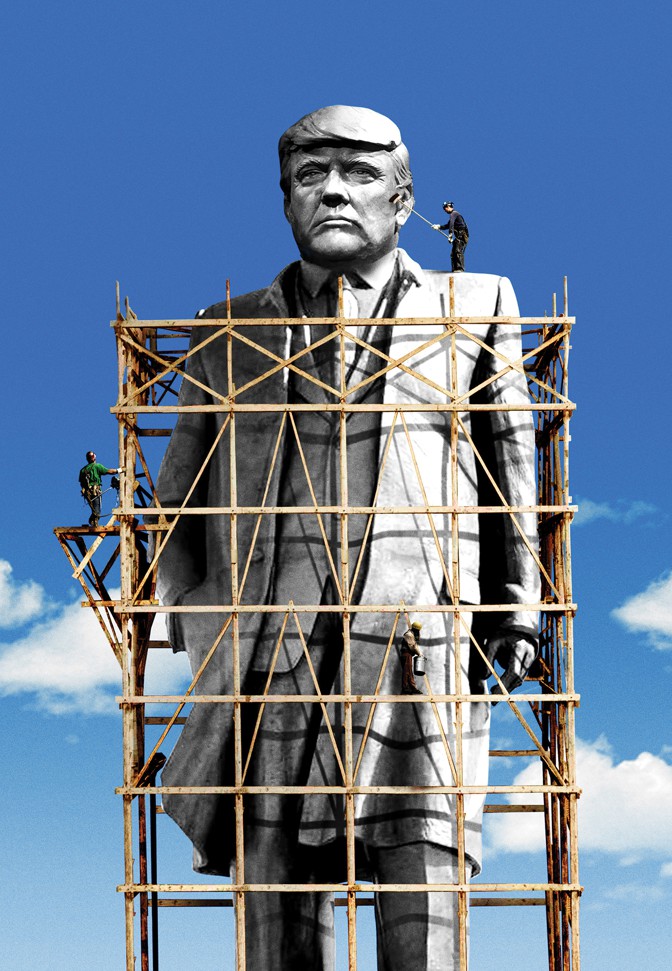

America’s Slide Toward Autocracy

Editor's Note: This article is part of a series that attempts to answer the question: Is democracy dying?

twenty-one months into the Trump presidency, how far has the country rolled down the road to autocracy? It’s been such a distracting drive—so many crazy moments!—who can keep an eye on the odometer?

Yet measuring the distance traveled is vital. As Abraham Lincoln superbly said in his “house divided” speech: “If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what to do, and how to do it.”

This article appears in the October 2018 issue.

Subscribe now to support 160 years of independent journalism. Starting at only $24.50. View more stories from the issue.

Let’s start with the good news: Against the Trump presidency, federal law enforcement has held firm. As of this writing, Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s inquiry is proceeding despite the president’s fulminations. The Department of Justice is ignoring the president’s Twitter demands to prosecute his opponents. As far as we know, the IRS and other federal agencies are not harassing Trump critics. In July, a police department in Ohio retaliated against a Trump adversary, the porn actress known as Stormy Daniels, by arresting her on now-dismissed charges that she touched undercover officers while performing at a strip club. But evidence indicates that this was entirely a local initiative.

Trump sometimes wins in court, as he did on his Muslim ban. He loses more often, as he did on separating immigrant children from their parents at the southern border. Politically charged cases are advancing through the legal system in traditionally recognizable ways.

More generally, Trump has been noticeably constrained by his unpopularity. He inherited a strong and growing economy. Casualties from America’s military actions have remained low. A more normal president, facing the same facts, might expect approval ratings like those of Bill Clinton during his second term: mid-50s or higher. Instead, Trump scrapes by in the low 40s.

In June, Gallup asked Americans to assess 13 aspects of Trump’s personality. Only 43 percent of respondents thought he cared about people like them. Only 37 percent found him honest and trustworthy. Only 35 percent said they admired him. Clearly, his erratic and offensive behavior, his overt racial hostility, and his maltreatment of women have taken a toll.

The bulk of this magazine issue is given over to questions about liberal democracy’s long-term viability. Around the world, democracy looks more fragile than it has since the Cold War. But if it survives for now in America, future historians may well conclude that it was saved by the president’s Twitter compulsion. Had he preserved a dignified silence for a few consecutive months, he might have bled less support and inflicted more damage on U.S. institutions. Then again, a Donald Trump with impulse control would not be Donald Trump.

Trump has built the worst-functioning White House in living memory, and its self-inflicted errors have slowed him down almost as much as his personality has. He traveled to Saudi Arabia, but never visited forward-deployed U.S. troops in the region. Potentially positive moments, like North Korea’s release of three detainees on May 10, 2018, are regularly squashed by stupidities, like the leak that day of a White House aide’s denigration of John McCain (“It doesn’t matter; he’s dying anyway”).

Yet even as Trump ties his own shoelaces together and lurches nose-first into the Rose Garden dirt, he has scored a dismaying sequence of successes in his war on U.S. institutions. In this, Trump is not acting alone. He is enabled by his party in Congress and its many supporters throughout the country. Republican leaders and donors have built a coping mechanism for the age of Trump, a mantra: “Ignore the weird stuff, focus on the policy.” But the policy is increasingly driven by the weird stuff: tariffs, trade wars, quarrels with allies, suspicions of secret deals with the Russians. The weird stuff is the policy—and it is transforming the president’s party in ways not easily or soon corrected. Maybe you don’t care about the president’s party. You should, because a liberal democracy cannot endure if only one of its two major parties remains committed to democratic values.

Here are the three areas of most imminent concern:

ETHICS

President Trump continues to defy long-standing ethical expectations of the American president. He has never released his tax returns, and he no longer even bothers to offer specious reasons, like a supposed audit. His aides shrug off the matter as something decided back in 2016.

Meanwhile, the president continues to collect payments from people with a vested interest in decisions made by his administration, from foreign governments looking to influence U.S. policy, and even from his own party. Those who seek the president’s attention know to patronize his hotels and golf courses. Authoritarian China has fast-tracked trademark protections for his family’s businesses. Trump’s disdain for ethical niceties has infected his Cabinet and his senior staff. It’s no longer much of a story when his commerce secretary is revealed to have filed false financial disclosures or when his top communications aide turns out to have worked to intimidate alleged sexual-harassment victims at Fox News. Or when his son-in-law is shown to have sought financing for business ventures from investors in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates at the same time that he was participating in the administration’s discussion about which of those countries to back in a military confrontation. If one gauge of authoritarianism is the merger of state power with familial economic interests, the needle is approaching the red zone.

SUBORDINATION OF STATE TO LEADER

At a July 20, 2018, ceremony, CEOs gathered in the White House to offer personal job-creation pledges to the president. Watch the video if you have not already; the scene recalls a rajah accepting accolades from his submissive feudatories.

Perhaps the most defining characteristic of modern autocrats such as Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Viktor Orbán, and Vladimir Putin is the way they seek to subsume the normal operations of government into their cult of personality. In a democracy, the chief executive is understood to be a public employee. In an autocracy, he presents himself as a public benefactor, even as he uses public power for personal ends.

Apparently to punish the Washington Post owner and Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos for his paper’s reporting, Trump has pressed the Postal Service to raise Amazon’s rates—thus warning other business leaders to be careful what they say. He has conscripted NFL team owners into his war against black football players who kneel during the national anthem to protest racism and police brutality.

Trump’s tariffs personalize power too. They enable him to privilege some industries and hurt others. Some losers—farmers, say—may be compensated; others, such as aerospace manufacturers, will be disregarded. All economic sectors must absorb the new truth that executive action can send their profits soaring (in July, not long after Trump imposed new tariffs on steel and aluminum, America’s largest steelmaker reported its highest second-quarter profits ever) or tumbling (shares of Molson Coors, which relies on cheap aluminum to make its beer cans, dropped 14 percent this spring after Trump’s tariffs were announced).

When Trump refers to “my” generals or “my” intelligence agencies, he is teaching his supporters to rethink how the presidency should function. We are a long way from Ronald Reagan’s remark that he and his wife were but “the latest tenants in the People’s House.”

ALTERNATIVE FACTS

Trump is hardly the first president to lie, even about grave matters. Yet none of his predecessors did anything quite like what he did in July: Travel to a U.S. Steel facility and brag that, thanks to his leadership, the company would open seven wholly new facilities. In reality, the company was reopening two blast furnaces at a single facility. You’d think his audience would know better, but the assembled employees cheered anyway.

Trump may not be much of a manager or developer, but he is a great storyteller. He has substantially shaped his supporters’ worldview, while successfully isolating them from damaging news. The share of Republicans with a positive opinion of the FBI tumbled from 65 percent in early 2017 to 49 percent this past July. In the past three years, Vladimir Putin’s approval rating among Republicans has almost tripled, to 32 percent.

To protect the president—and themselves—from the truth about Russia’s intervention in his election, Republican members of the House Intelligence Committee have concocted (and the conservative media have disseminated) an elaborate fantasy about an FBI plot against Trump. The party’s senior leaders know that the fantasy is untrue. That’s why they squelch attempts to act on the fantasy by opening a special-counsel investigation into the bureau. But they cheerfully allow their supporters to believe the fantasy—or to believe it just enough, anyway, to get revved up for the midterm elections.

Many americans want to believe that Democratic victories in November will reverse the country’s course. They should be wary of investing too much hope in that prospect. Should Democrats recover some measure of power in Congress, their gains could perversely accelerate current trends. As Republicans lose power in Washington, Trump will gain power within his party.

Today, Republicans queasy about Trump can look to House Speaker Paul Ryan or Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell as alternative sources of power or patronage in Washington. But if the party loses hold of Congress, congressional Republicans’ clout will dwindle. Power will be divided in Washington between Trump and the Democrats. If legislative success becomes a vanishing possibility, the White House may begin testing the limits of its authority more aggressively.

Trump will face more hearings, more investigations, and generally more trouble than he faces today. Partisan loyalties will be engaged as Republicans rally around their embattled leader. The conservative pundit M. Stanton Evans quipped, “I didn’t like Nixon until Watergate.” A joke then describes reality today. Among Trump supporters, “No collusion!” has already evolved into “Collusion is not a crime,” with “Collusion is patriotic” perhaps soon to follow. Trump supporters have no exit ramp. Party affiliation has hardened since the 1970s into a central aspect—in many ways the central aspect—of personal identity. If Trump is exposed and repudiated, his supporters will be discredited alongside him. If he is to survive, they must protect him.

In an ultrapolarized post-November environment, the Republican Party may radicalize further as it shrivels, ceasing to compete for votes and looking to survive instead by further changing the voting system. Donald Trump is president for many reasons, but one is the astonishing drop in African American voter participation from 2012 to 2016. It’s not surprising that Hillary Clinton inspired lower black voter turnout than Barack Obama did in 2012. It issurprising that she inspired lower black turnout than John Kerry did in 2004. But in the intervening years, the rules were changed in ways that made voting much harder for non-Republican constituencies, particularly black people—and the rules continue to be changed in that direction.

You may know the story of American democracy as a series of suffrage extensions, culminating in the reforms of the 1960s and ’70s. But voting rights have just as often been rolled back at the state and local levels—the literacy tests and poll taxes of the Jim Crow South are the best-known examples. Since 2010, that history of state-pioneered ballot restrictions has repeated itself, and if Republican power holders feel themselves especially beset after 2018, the rollbacks may continue.

We cannot blame democracy’s troubles in the United States or overseas on any one charismatic demagogue. Many of today’s authoritarians are notably uncharismatic. They flourish because they command political or ethnic blocs that, more and more, prevail only as pluralities, not majorities. So it is with Trump.

Free societies depend on a broad agreement to respect the rules of the game. If a decisive minority rejects those rules, then that country is headed toward a convulsion. In 2016, Trump supporters openly brandished firearms near polling places. Since then, they’ve learned to rationalize clandestine election assistance from a hostile foreign government. The president pardoned former Sheriff Joe Arpaio, convicted of contempt of court for violating civil rights in Maricopa County, Arizona, and Dinesh D’Souza, convicted of violating election-finance laws—sending an unmistakable message of support for attacks on the legal order. Where President Trump has led, millions of people who regard themselves as loyal Americans, believers in the Constitution, have ominously followed.

Once violated, democratic norms are not easy to restore, as Rachel Kleinfeld of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has observed. In the wake of Silvio Berlusconi’s corrupt tenure as prime minister, Italy is now governed by a strange coalition of extremist parties. Nominally of the right and the left, they share a dislike of the European Union, affinity for Putin’s Russia, and distrust of vaccines. Fate struck down the demagogic Louisiana governor Huey Long, but his family bestrode the state’s politics for decades after his death. Argentina, emerging from neo-Peronism, has stumbled on its way back to legality.

Weakened institutions will be challenged from multiple directions: We are already hearing liberals speculating about 1930s-style court packing as a response to Trump’s cramming of the judiciary. The distrust of free speech on campus is being carried by recent graduates into their jobs and communities. We see in other countries, especially the United Kingdom, the rise of an activist left nearly as paranoid and anti-Semitic, as disdainful of liberal freedoms and democratic institutions, as the so-called alt-right in the U.S.

It could happen here. Restoring democracy will require more from each of us than the casting of a single election ballot. It will demand a sustained commitment to renew American institutions, reinvigorate common citizenship, and expand national prosperity. The road to autocracy is long—which means that we still have time to halt and turn back. It also means that the longer we wait, the farther we must travel to return home.

This article appears in the October 2018 print edition with the headline “Building An Autocracy.”

No comments:

Post a Comment