The Suicide of a Great Democracy

We had made plans to go to Washington weeks ago, and there was no way to change the trip. The train was almost empty when it pulled into Union Station on Friday night. The next morning, we went out into the dead heart of the city. The government shutdown was in its third week. Nearly all the museums that would have interested the kids were closed, and so were the ones that would have bored them. There was nothing to do except wander around, but the crowds we expected in the district center were absent, the streets and sidewalks almost empty. Without people, the scale of the capital dwarfed us. Each mid-century concrete building looked like its own walled city, the National Mall was a vast plain, and an endless highway separated the White House and the Capitol dome. It was as if Washington had been stricken by a grotesque illness that caused the body to swell up and suffocate the spirit within. The federal city was one great sarcophagus.

The Atlantic’s Year in Review

Stories worth revisiting, podcasts and videos you might have missed, and more from 2018.

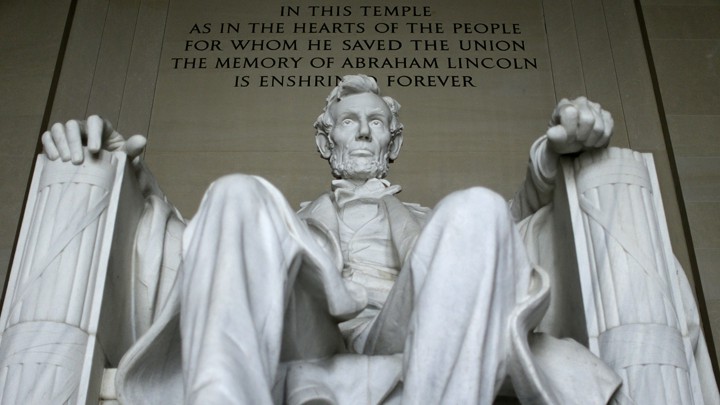

We wandered across the mall to see the monuments, which are always open. We climbed the marble steps of the Lincoln Memorial. There was the somber giant in his chair. Our 7-year-old daughter’s eyes filled, and she read out the Gettysburg Address: “A new birth of freedom … government of the people, by the people, for the people.” The second inaugural was too much for her, and she asked me to read it.

And the war came … Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword … let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds …

It shamed me to read it. Abraham Lincoln’s eloquence touched levels of morality and high resolve that were preposterously out of reach in the first days of 2019, in the third year of the Trump presidency.

A constant theme runs throughout Lincoln’s writings, from his years as a young Illinois politician to the last great speeches of his life: the supreme value of self-government. Everything depended on this idea, “our ancient faith,” which itself was “absolutely and eternally right.” But its endurance was never guaranteed. From the start of his career, Lincoln foresaw how American democracy might end—not through foreign conquest, but by our own fading attachment to its institutions. “If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher,” he said in 1838. “As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”

Self-government required that the union should live, and it also negated slavery. Lincoln never believed in political and social equality between the races—instead, he built his argument against slavery on the founding words of the republic. In 1854, after Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, abolishing the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and allowing the extension of slavery into the new territories, he told a crowd in Peoria, Illinois: “If the negro is a man, is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself? When the white man governs himself that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism … No man is good enough to govern another man, without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle—the sheet anchor of American republicanism.”

During the Civil War, the government never shut down—not even when the capital was threatened by Confederate troops. A shutdown would have undermined the foundation of Lincoln’s cause, which was the ability of free people to rule themselves. The paralysis and dysfunction would have told the world that the government he led was no longer fully devoted to the cause for which other Americans had given the last full measure of devotion. A shutdown would have looked like the beginning of the end that Lincoln always knew was possible.

It makes sense that Donald Trump is indifferent to the paralysis of the government he leads, and that he welcomes a shutdown of months or even years. If shutdowns become routine, if politicians view the government in which they serve as a disposable tool, if we’re no longer capable of governing ourselves, this only reflects Trump’s contemptuous attitude toward democracy itself. Shuttered museums, federal workers who can’t pay their bills, national parks with stinking toilets: This is what Trump thinks of American republicanism. This is what the suicide of a great democracy looks like.

So we stayed for a while at the Lincoln Memorial and read the words carved into its walls, to recall what makes America great if anything does.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

GEORGE PACKER is a staff writer for The Atlantic. He is the author of The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America and the forthcoming Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century.

No comments:

Post a Comment