‘Eliminate Every Superfluous Word’

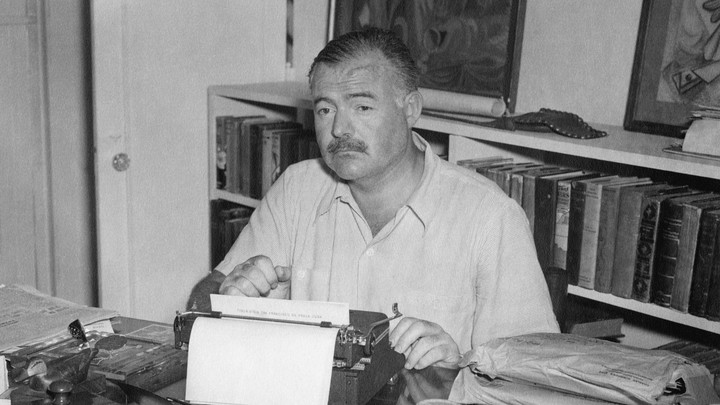

Ken Burns’s new documentary, Hemingway, dramatizes one of the great revolutions in the history of American literature.

JAMES PARKERHis poor head, you keep thinking as you watch Ken Burns’s Hemingway. His poor bloody head. Even the corroded voice of Peter Coyote, whose narration is a study in American understatement, goes up a semitone as Hemingway—in a plane crash in Uganda, this time—sustains “yet another major head trauma.” Nine in total, spaced throughout his adult life. And that doesn’t include whatever shots he may have taken while he was boxing or drunkenly fistfighting. War to war, wife to wife, novel to novel, in all of his adventurings and embracings and abandonings, his most constant mistress may have been concussion.

Hemingway doesn’t include my favorite Hemingway story: Paris, mid-1920s, he’s out drinking with James Joyce, and the great Irishman—frail and half-blind but obstreperous in his cups—starts fights he can’t finish. “Deal with him, Hemingway! Deal with him!” (Hemingway himself told that one, so it may well not be true.) But there are plenty of other vignettes to chew on across the six hours of Burns’s documentary; the montage of Hemingway-ness is not exactly lacking in incident. Grandly shirtless, he’s hauling tuna from the Gulf of Mexico; in Paris, he’s test-tubing his prose in the aesthetic laboratories of Ezra Pound (“Make it new!”) and Gertrude Stein (“A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”); in Madrid, he’s breakfasting under artillery fire at the Hotel Florida; and in 1944, he’s glimpsed loping through the death mill of the Hürtgen Forest, weapon in hand, after three wars finally and with grim joy an (unofficial) combatant for the first time.

The revolution of his style is hard to discern, because to a degree we’re still in it. “Use vigorous English,” counseled the copy style sheet of the Kansas City Star, his first home as a journalist. “Be positive, not negative. … Eliminate every superfluous word.” Hemingway’s voice distilled itself with miraculous speed, a fusion of telegrammatic urgency and high modernist impersonality, with counterpoint learned from Bach and rhythms located profoundly in his own neurology; entire species of literature went extinct overnight. In the most beautiful way, it was anti-writing:

Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterwards the road bare and white except for the leaves.

That’s from the legendary opening of A Farewell to Arms. Leaves, four times, each time a different vibration. A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose. “I read that paragraph and I want to cry,” confesses a literary scholar in Hemingway.

Let’s talk about the Burns Method: the frowning pan across the blotchy manuscript page, the dreamy plunge into the old photograph, the smatters of ambient sound, the talking head who is not so much a talking head as a deeply invested witness. How do you dramatize the interior life? How do you dramatize writing? If you’re Ken Burns, by talking to writers, by watching their faces and bodies register the Hemingway-shocks. “The value of the American declarative sentence, right?” says Tobias Wolff, pulsing with admiration. Edna O’Brien, magically hushed and priestess-like, reads aloud from his date-rape story, “Up In Michigan”—“She was cold, and miserable, and everything felt gone”—and asks: “Could you, in all honor, say that this was a writer who didn’t understand women’s emotions, and who hated women? You couldn’t. Nobody could.”

Then there are the voice-overs: Jeff Daniels doing Hemingway, Meryl Streep doing the ass-kicking Martha Gellhorn (who says that Hemingway, while writing, is “about as much use as a stuffed squirrel”), and—with wonderful warmth—Keri Russell as Hemingway’s first wife, the passionate Hadley. “Oh Mr. Hemingway, how I love you. … Your flannel shirt seems a strangely beautiful thing, and it smells so good besides. Some day, if I don’t watch out, there’ll be a poem on the smell of a clean white shirt that’ll raise up the hair on the dead.”

Death In the Afternoon, his sprawling, hybrid book about the bullfight, was my Hemingway text. A manual, a memoir, a manifesto, a poetic anthropology: As a bullfight-obsessed schoolboy, I inhaled it, relishing without quite understanding its distinctness. There are black-and-white photographs in the book, one of which features a sheeted corpse on a slab, surrounded by 16 well-dressed men. “Granero dead in the infirmary,” reads Hemingway’s caption. “Only two in the crowd are thinking about Granero. The others are all intent on how they will look in the photograph.”

Fascinated, you scan the picture. Two men are looking down at the dead matador; the rest are arranging themselves in various ways for the camera. One of the men looking down is sweating, pop-eyed, in a state of naked distress. We can be satisfied that he is thinking about Granero. The other, with a well-groomed mustache, looks impressively grave. Too impressively grave. Sort of lacquered with solemnity. He’s posing, surely. He’s thinking about himself. Has Hemingway been taken in? Then, at the side of the picture, almost squeezed out, you see another man: He too is looking down. His face is beyond grief; it holds nothing, only a kind of animal respect, emptied out in the presence of death. This is the second man who is thinking about Granero. Who but Hemingway would have zeroed in like this?

Death—the sight of it, the smell of it, the immanence of it—was his fetish. He stalked it in battles, bullfights, big-game hunts. And it stalked him back: Should he kill himself? His father did, with his father’s Civil War revolver. By disappearing briefly after that plane crash in Uganda, presumed dead by the world’s media, Hemingway achieved every writer’s dream: He got to read his own obituaries. And indeed there was a strange already-deadness to Hemingway as he battered his way through life. A kind of radiant nihilism, most un-American, diffused its halo around him. “Hail nothing full of nothing, nothing is with thee.” It made him wildly brave.

At a some point in Hemingway, it’s hard to say exactly when, the light in his eyes goes out. The hard, vulnerable, darkly shining gaze of the early photographs is sealed over by something else. The eyes, in the bashed-up face, become unreadable crescents of shadow. He looks sad and mean. Decades of booze, for sure, but also what the forensic psychiatrist Andrew Farah—the author of Hemingway’s Brain and one of Burns’s interviewees—has straightforwardly diagnosed as a case of brain damage. The talent degenerates. The talent dies before the man. Trying to write, Hemingway keeps arriving at “the complete blankness.”

The writer “does his work alone,” Hemingway had written in his 1954 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.” This impossible standard, this merciless knowledge. It was his curse, in a way: to be good enough to know when he was done.

No comments:

Post a Comment