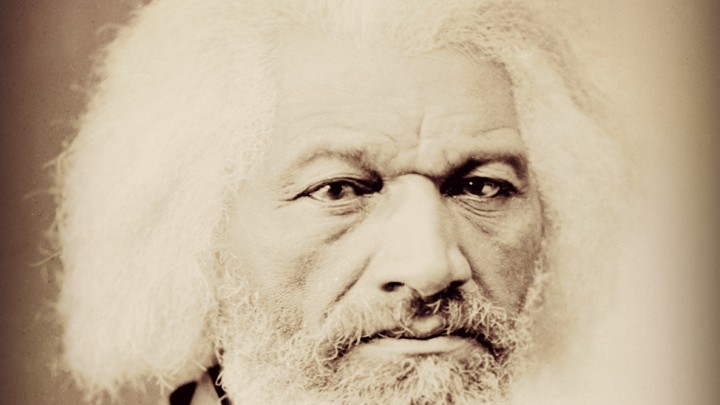

Frederick Douglass, Defender of the Liberal Arts

In a speech delivered at the 1894 dedication of the Manassas Industrial School for Colored Youth, which was founded to provide technical education for African Americans, Frederick Douglass argued that learning and liberty went hand in hand. He underlined the importance of education as part of a process of realizing human potential, furthering justice, and achieving freedom: "Education…means emancipation," he said. "It means light and liberty. It means the uplifting of the soul of man into the glorious light of truth, the light only by which men can be free. To deny education to any people is one of the greatest crimes against human nature."

Get the latest issue now.

Subscribe and receive an entire year of The Atlantic’s illuminating reporting and expert analysis, starting today.

As a former slave, Douglass well understood the weight of chains and the yearning to break free; he also believed in the value of vocational training that increased students’ economic potential. Yet, as Douglass demonstrated, the emancipation that comes from education is not confined to economic empowerment. Douglass’s own life testified to the ability of the liberal arts—fields such as literature, philosophy, the physical sciences, and social sciences—to inspire internal emancipation as well.

Douglass’s example offers a helpful corrective to the tendency of contemporary education debates to fixate on economic questions. On both sides of the aisle, many policymakers assume that public education’s principal goal is to teach students marketable skills so that they can become productive economic actors. This assumption helps explain the widespread celebration of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) and de facto mockery of many liberal-arts degrees—especially those infamous art-history majors. The Obama administration, too, often frames education policy as an economic issue. Just look at the White House’s website on education: "To prepare Americans for the jobs of the future and help restore middle-class security," it reads, "we have to out-educate the world and that starts with a strong school system." In a similar vein, states across the country are deliberating over whether the liberal arts still have a role in education; a debate recently erupted in Wisconsin, for example, after a gubernatorial budget proposal (whether mistakenly or not) called for the public university system to forfeit "the search for truth" as an official purpose and instead focus solely on training students for in-demand jobs.

Douglass reveals that a single-minded focus on education as a vocational enterprise risks obscuring other important aims—including personal development, ethical maturation, and preparation for civic life. Producing students who are able to succeed in the workforce is a worthy goal, but vocational skills need to be enriched by a more holistic, humanistic perspective. Since their early formalization in the ancient world, the liberal arts have helped develop this perspective. Again, the liberal arts and vocational skills are not diametrically opposed—the kind of critical thinking encouraged by the former can be useful in any profession, for instance. But the liberal arts offer more than indirect economic benefits. They can, for example, nurture the thoughtfulness important in a free society.

In an 1853 letter to Harriet Beecher Stowe that exemplified his interest in vocational education, Douglass didn’t call for the creation of new colleges to serve African Americans. Instead, he sought schools that would teach "agriculture and the mechanic arts." Douglass argued that teaching vocational skills—especially industrial ones—to African Americans would help them climb the ladder from slave to integrated freeman. A prosperous, upwardly mobile African-American working class would, he thought, offer a profound refutation of many pro-slavery arguments, which held that African Americans were incapable of economic self-sufficiency.

Douglass’s interest in practical training is in harmony with the thinking behind contemporary efforts to expand economic opportunity—especially to students from disadvantaged backgrounds—by promoting vocational programs and targeted enterprises such as Project Lead the Way. But his memoirs demonstrate that practical training is hardly enough. In his 1845 autobiography, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, he chronicles his efforts to fashion an identity as a free man, offering a bracing portrait not only of the physical hardships of slavery but also of its psychological torments. "You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man," Douglass wrote.

Crucial to these efforts was gaining knowledge. While the American slavery system depended on physical force, it also relied on a web of mental and spiritual coercion. In his quest to become a free man, Douglass had not only to break his physical bonds; he also had to pare back that web strand by strand in order to claim knowledge about himself and the world. Like many others born a slave, Douglass did not know for certain his birth date or the identity of his father, and the mystery of his origins pained him. As he wrote, "The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege." Early in his life, then, Douglass saw that enforced ignorance was a key tool of slavery. For example, one of Douglass’s owners became enraged when he found out his wife was teaching him how to read, declaring, according to Douglass, that a slave "should know nothing but to obey his master—to do as he is told to do." Reading would "forever unfit him to be a slave" because it would make him "unmanageable."

The master’s threats failed to dissuade Douglass, who eventually taught himself literacy and later described his experience reading The Columbian Orator, an anthology edited by a Massachusetts school teacher, as a turning point in his life. Reading this liberal-arts anthology, which drew from sources ranging from speeches to play excerpts, arguably helped Douglass deliver a decisive cut to slavery’s psychological web. Reflecting on some of the anthology’s works, he wrote, "They gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul, which had frequently flashed through my mind, and died away for want of utterance ... The reading of these documents enabled me to utter my thoughts and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery."

In defiance of the imperative that a slave must be an uncritical instrument of his master’s will, Douglass’s encounter with The Columbian Orator and other works encouraged the exploration of his humanity. The more Douglass read, the more dissatisfied he became with his condition and the deeper he yearned for freedom. He became better able to articulate a conceptual challenge to the reigning ideology of slavery.

Even Douglass’s advocacy in favor of vocational training speaks to the importance of a liberal education. His letter to Stowe argued that colleges would soon become important for the progress of African Americans. In fact, the Manassas Industrial School, which lasted as a private institution until the 1930s, placed a major emphasis upon the liberal arts, too, instructing students in literature, history, and the sciences on top of topics such as sewing and carpentry.

Since the founding of the United States, many public figures have emphasized the civic benefits of a liberal education. When Thomas Jefferson wrote that one of the principal ways to ward off tyranny was to "illuminate ... the minds of the people at large," he presumably had more in mind than job-skills training. The liberal arts, in other words, can pay civic dividends.

A republic is more than an economy, and realizing the promise of the Declaration’s "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" involves more than GDP growth. The Columbian Orator did not directly train Douglass to be a better farmer or mechanic or order-follower. Instead, it exposed him to new intellectual horizons, inspired him with beautiful turns of phrase, and enriched his ethical perspective. In short, it helped him become a free man.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

E. THOMAS FINAN is a lecturer in humanities at Boston University. He is the author of The Other Side.

No comments:

Post a Comment