The Famous Baldwin-Buckley Debate Still Matters Today

In 1965, two American titans faced off on the subject of the country’s racial divides. Nearly 55 years later, the event has lost none of its relevance, as a recent book attests.

GABRIELLE BELLOT“The American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro,” James Baldwin declared on February 18, 1965, in his epochal debate with William F. Buckley Jr. at the University of Cambridge. Baldwin was echoing the motion of the debate—that the American dream was at the expense of black Americans, with Baldwin for, Buckley against—but his emphasis on the word is made his point clear. “I picked the cotton, and I carried it to the market, and I built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing,” he said, his voice rising with the cadences of the pulpit. “For nothing.”

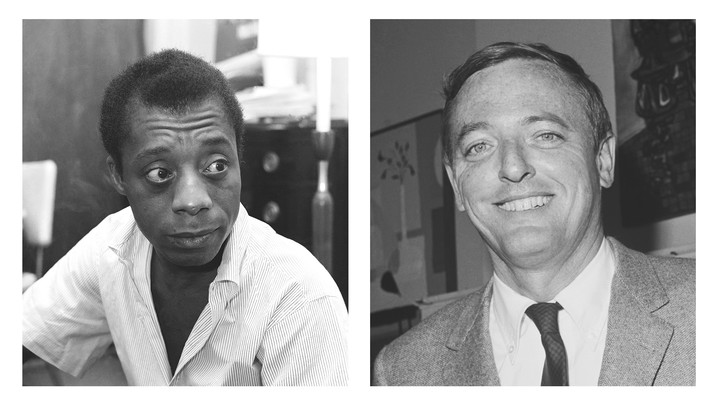

The packed auditorium was hushed. Here was a clash of diametrically opposed titans: In one corner was Baldwin, short, slender, almost androgynous with his still-youthful face, voice carrying the faintly cosmopolitan inflections he’d had for years. He was the debate’s radical, an esteemed writer unafraid to volcanically condemn white supremacy and the antiblack racism of conservative and liberal Americans alike. In the other corner was Buckley, tall, light-skinned, hair tightly combed and jaw stiff, his words chiseled with his signature transatlantic accent. If Baldwin—the verbal virtuoso who wrote moving portraits of black America and about life as a queer expatriate in Europe—stood for America’s need to change, Buckley positioned himself as the reasonable moderate who resisted the social transformations that civil-rights leaders called for, desegregation most of all. Some of the students in the audience knew him as nothing less than the father of modern American conservatism.

The famed debate, its riveting lead-up, and its aftermath are the subject of The Fire Is Upon Us, an exhaustive new study by Nicholas Buccola. In the first book to focus exclusively on this event, Buccola, who teaches political science at Linfield College, traces Baldwin’s and Buckley’s respective upbringings and political awakenings amid an America polarized by the issues of desegregation and racial equality. Understanding how each man came to his own conclusion, the book argues, can offer sharp insights into why Americans remain so at odds on the realities of racism today.

If not for the 1965 debate, Baldwin might never have met Buckley. In fact, Baldwin nearly had another opponent altogether. Before the Cambridge Union invited Buckley, it had reached out to staunchly segregationist politicians, all of whom declined. Buckley seemed an ideal alternative: an articulate, prominent sociopolitical critic who eschewed the racist epithets of conservatism’s more vocal white supremacists but who nonetheless supported segregation. As Buccola writes, Buckley saw the debate as a chance to defeat one of his ideological archnemeses on a public stage.

To Buckley’s irritation, though not entirely to his surprise, Baldwin delivered a rousing performance. “It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, or 6, or 7,” Baldwin declared during the debate, “to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you.” He argued that the evils of slavery had hardly been exorcised after abolition, but that rather, the country was essentially still the same for black Americans as it was during the days of legal slavery. After he spoke, he received a standing ovation.

When it was his turn, Buckley argued that Baldwin was being treated with kid gloves, so to speak, because he claimed to be a victim. “The fact that your skin is black,” he averred, “is utterly irrelevant to the arguments you raise.” Baldwin, he said slowly and full of a quiet anger, was a violent enemy of the southern way of life who delivered “flagellations of our civilization” and of America as a whole. Forcing the American South to abandon its way of life and accept government-mandated integration, he insisted, would be immoral. Ultimately, the audience disagreed, and Baldwin won the debate, 540 to 160.

It’s difficult to talk about either Baldwin or Buckley without referencing this contest; it has become a touchstone in both men’s lives, memorialized, for instance, in Raoul Peck’s landmark 2016 documentary on Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro. Although the ostensible focus of The Fire Is Upon Us is the Cambridge debate, more than half of it is devoted to explaining how Baldwin’s and Buckley’s upbringings informed their ideological beliefs and how they became rising stars in their respective worlds. Buccola doesn’t privilege Baldwin or Buckley, and chapters feature alternating sections devoted to each. Although some of the early segments and transitions feel rushed or awkward, the author paints a solid picture of each man once the book hits its stride.

Read: The imperfect power of ‘I Am Not Your Negro’

The Fire Is Upon Us is written for readers on both the left and the right, its prose wonderfully accessible even for an audience that may be only superficially familiar with either Baldwin’s or Buckley’s work. Though he makes it clear by the end that his own ideological sympathies lie with Baldwin’s calls for racial justice, Buccola gives ample room to examining both men’s ideologies, without—and this is crucial—suggesting that Buckley’s racist views were somehow acceptable. (Perhaps because the bulk of the book focuses on the debate and its lead-up, Buccola delves less into the sometimes surprising ways in which Buckley’s public declarations on race shifted over the ensuing decades, with Buckley going so far as to suggest in 1970 that a black man should be elected president in the 1980s.)

Buccola’s study starts by examining the striking differences in how Baldwin and Buckley were raised. While Baldwin grew up poor in Harlem, Buckley was surrounded by privilege. His mother, Alöise Steiner Buckley, filled their home with servants and tutors for her 10 children. She was deeply Catholic, the seed of the rigid, Manichaean religious views that her son would adopt. Throughout his life, Buckley would become well known for the strict division of “good” and “evil” in his worldview, whereby Catholicism and capitalism were good, and atheism and socialism exemplified evil.

It was also clear to Alöise’s progeny what she thought about who should serve whom in American society. She was “a racist,” Buckley’s brother Reid recalled, because she “assumed that white people were intellectually superior to black people,” yet he added that “she truly loved black people and felt securely comfortable with them from the assumption of her superiority in intellect, character, and station.” This peculiar, patronizing dynamic presaged William’s own ideology, in that both mother and son believed in retaining barriers between black and white Americans as part of southern culture. As an adult, Buckley would often write that segregation was a temporary necessity, because black Americans were “not yet” advanced enough to be equal to whites, implying, with a condescension he perhaps thought uplifting, that they might one day be on the same level.

Still, Buckley considered himself different from the racist demagogues on the right. He viewed conservatives such as Strom Thurmond and Alabama’s pro–Jim Crow governor George Wallace as crass fringe elements, believing himself gentler and more sympathetic. Yet in reality, as Buccola points out, his views were simply a softer, more patrician version of white supremacy. Buckley believed that, as Buccola puts it, “a combination of noblesse oblige and constitutional principle might reform [the South] over time,” rather than immediate desegregation. “Buckley’s slogan,” Buccola wryly continues, “might be ‘Some Freedom … one day … when we decide you’re ready.’”

Buckley’s support of the South’s right to segregation and Baldwin’s condemnations of white America took place against the backdrop of a deeply divided America. Perhaps no statement better demonstrated that divide than what William Faulkner notoriously told Russell Warren Howe in 1956 when asked for his thoughts about “forcing” southern whites to accept integration. Though Faulkner claimed to eschew racial prejudice, he believed in the South keeping its way of life without government interference. “I don’t like forced integration any more than I like enforced segregation,” he answered. “If I have to choose between the United States government and Mississippi, then I’ll choose Mississippi … if it came to fighting I’d fight for Mississippi and against the United States even if it meant going out into the street and shooting Negroes.” (Faulkner later claimed to have been misquoted, though there is no definitive evidence of this.) Faulkner would turn to violence to prevent integration, because segregation was—as Buckley would repeatedly say—a southern way of life.

Baldwin had flashed onto Buckley’s radar before. But with the 1962 publication of “Letter From a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin’s masterful indictment of white supremacy and reflection on the debilitating narrowness of his religious upbringing in The New Yorker, Buckley decided to pay special attention to this rising figure from Harlem. He was furious that Baldwin had attacked Christianity and white people all at once—and, worse, that he’d been given a major platform to do so. “James Baldwin is a disarming man,” began a piece by Garry Wills that Buckley commissioned for National Review, Buckley’s magazine, as a rebuke of Baldwin’s essay. Though Wills castigated Baldwin for blasphemy and for calling for “an immediate secession from [Western] civilization,” Wills had particular scorn for the literati who “failed” to be “angry” at Baldwin’s damning arguments. At the end of his essay, Wills acknowledged that Baldwin “is an adversary worthy of our best arguments.” Buckley, manifestly, felt the same.

As Buccola details, Baldwin, unlike Buckley, had suffered greatly before achieving fame as an author. He’d left New York in 1948, nearly penniless, for France, after deciding he could no longer survive the traumatizing racism of America—in northern and southern states alike. Though he found some respite in Paris, he still nearly committed suicide there after being arrested by the police on suspicion of having stolen a hotel’s bedsheet (which he had not). And he kept returning to America, both in his books and in his travels. He never hid away; instead, The Fire Is Upon Us argues, he put himself on the front lines of a civil-rights battle for nothing less than America’s soul.

Baldwin was proud of winning the Cambridge debate, but frustrated that Buckley, like so many other white Americans, had seemingly failed to understand what he was trying to say—almost like Ludwig Wittgenstein’s famous proposition in Philosophical Investigations that “if a lion could speak, we could not understand him,” for it would be speaking a language and of a reality alien to our own. They each had different “systems of reality,” Baldwin said during the debate; they were two lions of their field who were able to spar, but unable to comprehend each other.

Though a work of history, The Fire Is Upon Us holds a mirror up to the strident political and racial divisions of the U.S. in 2019. The language may be a little different today from what Baldwin and Buckley used, but the sharp terms of the debate over whether people of color in the United States get to have the American dream remains the same then as now. “The economic, educational, and health disparities across the color line,” Buccola writes at the end, “… happen because all of us allow them to happen, and until we summon the will to recognize this fact and do something about it, the American dream will remain a nightmare for many.” Buccola, like Baldwin, asks white Americans to acknowledge their complicity in the foundational inequalities that structure the country from bottom to top. Liberals and conservatives alike, the author argues, still have as much work to do today as they did in Baldwin’s day to reshape that nightmare into a dream worth striving for.

No comments:

Post a Comment