What Biden Understands That the Left Does Not

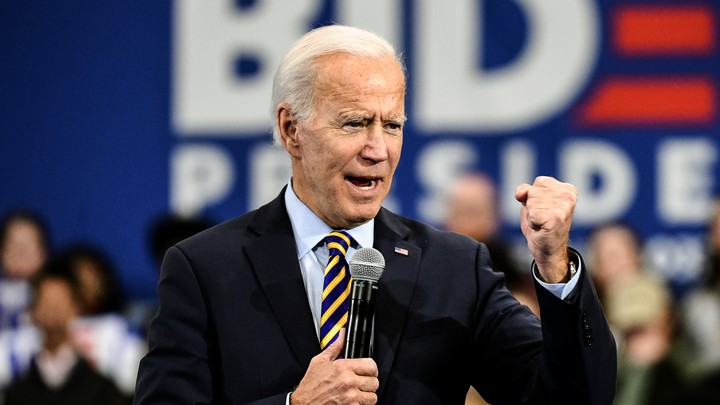

All through the primaries, Joe Biden was portrayed as an anachronism, a man who had missed his moment by a decade or three. Even as mainstream media outlets published fawning profiles of his many rivals, they largely dismissed his chances. Most pundits seemed to believe that nobody would support Biden if he didn’t happen to be the most senior Democrat in the race. But Biden not only beat a dozen competitors to win the Democratic Party’s nomination he has also persistently led Donald Trump in the polls, adeptly handling the extraordinarily turbulent politics of 2020.

Experience The Atlantic Festival. Wherever you are.

Join today’s brightest minds and boldest thinkers at our first-ever virtual festival, September 21-24.

Read: What Americans don’t know about Joe Biden

The simplest explanation is that people like Joe Biden, and they like him for a reason: In contrast to Trump and certain vocal parts of the Democratic Party, he actually expresses the view of most Americans. If Democrats manage to win back the White House—and avert the danger that four more years of Trump would pose to peace, unity, and democracy in America—it will be thanks to qualities that a younger or more radical candidate would probably lack.

When mass protests over the killing of George Floyd spread across the United States, the American public reacted in a far less divided way than a quick look at the partisan media landscape might suggest. According to opinion polls, most Americans believe that Derek Chauvin committed murder, that police brutality is a serious problem, and that we need to do more to eliminate racism. Other polls show that most Americans also believe that violent protest is illegitimate and that it is a bad idea to “defund the police.”

But many political and media elites have failed to capture this consensus. The worst offender is, as always, Donald Trump, who seems unable to express empathy for those who suffer from injustice, and still seems to think that he can boost his standing by inflaming the country’s racial tensions. But some on the left have also veered toward the extremes. They have embraced deeply unpopular messages such as “defund the police,” or refrained from criticizing violent protesters.

In the past few months, writers for publications including The Nation and The New York Times have dismissed the idea that looting and rioting are forms of political violence. Just a few days ago, NPR published a soft interview with a white author who defends looting by claiming that it “strikes at the heart of property, of whiteness and of the police.” And anyone on Twitter will have seen numerous versions of the argument that rioting and looting aren’t happening at a significant scale, that it doesn’t matter if they are happening, and that at any rate, such behavior is a reasonable reaction to injustice.

This abdication of moral responsibility by parts of the commentariat has made it more difficult for elected Democrats to oppose political violence. On Saturday, for example, Senator Chris Murphy wrote on Twitter: “This isn’t hard. Vigilantism is bad. Police officers shooting black people in the back is bad. Looting and property damage is bad. You don’t have to choose. You can be against it all.” When some social-media users criticized his message, he took it down, and apologized for giving the impression that he “thought there was an equivalency between property crime and murder.”

Read: The double standard of the American riot

Murphy was right the first time: It shouldn't be hard to support peaceful protests for racial justice while unequivocally denouncing looting. But evidently, the easy test proved too hard for him to pass.

On the ground, the failure to pass this same test has had dire consequences. Authorities in Portland, Oregon, have, in all but the most egregious cases, declined to press charges against protesters who break the law. One man who benefited from this policy is Michael Reinoehl, a white man who wrote on social media that “every Revolution needs people that are willing and ready to fight ... I am 100 % ANTIFA all the way!”

In July, Reinoehl was apprehended at a local protest for being in possession of a loaded gun and resisting arrest. But he was quickly let go. A few weeks later, the charges against him were dropped. On Saturday, he attended a protest in Portland, where he allegedly shot and killed a Trump supporter. (Reinoehl was killed Thursday night when a federal fugitive task force moved to arrest him.)

As george packer has rightly noted in these pages, the violent clashes in Kenosha, Wisconsin; Portland; and other cities around the country have opened a big opportunity for the incumbent president: "If Donald Trump wins, in a trustworthy vote, what’s happening this week in Kenosha, Wisconsin, will be one reason." Voters, Packer said, believe Democrats are being sincere when they denounce police brutality. But do they also believe that Democrats are being sincere when they criticize political violence—often, like Murphy, rather gingerly?

Thankfully, most Black officials and community leaders have ignored online hand-wringing about the perils of criticizing lawlessness. They have wholeheartedly embraced the mass movement for racial justice—and unreservedly condemned the extremists and opportunists who loot stores, burn down neighborhoods, or engage in juvenile fantasies of political revolution.

Black politicians including Keisha Lance Bottoms, the mayor of Atlanta, and John J. DeBerry Jr., a Democratic state representative in Tennessee, have denounced those intent on destruction. Citizens with the most personal reasons to seek revenge, including George Floyd’s brother and Jacob Blake’s mother, have made moving pleas not to descend into disorder.

Read: The new Southern strategy

The Democratic Party’s nominee for president has also condemned violence early, often, and without ambiguity. On June 2, Biden made clear that he does not condone riots, no matter the cause they supposedly serve: "There is no place for violence, no place for looting or destroying property or burning churches, or destroying businesses.”

Since then, Biden has repeatedly made the same point much more directly than many of his colleagues have. In a live speech from Pittsburgh on Monday, he drove the point home: "Rioting is not protesting. Looting is not protesting. Setting fires is not protesting," he insisted. "It's lawlessness, plain and simple. And those who do it should be prosecuted."

Perhaps the most powerful moment of Biden's speech came when he dismissed, with a wry smile, the idea that he might have secret sympathies for political violence: "Do I look like a radical socialist with a soft spot for rioters? Really?"

The question biden put to the American people in Pittsburgh is whether they would feel safer under his watch or that of a president who, in hope of political gain, has embraced chaos for the past three months. Polls suggest an answer. Some 40 percent of Americans say that a Biden victory would make them feel less safe. But that figure is 50 percent for Trump.

As long as Biden continues to be as emphatic about his views as he was on Monday, voters will see that his disavowal of violence is sincere. And if they are faced with a decision between a president who is forever making excuses for those who commit violence in his name, and a challenger who is willing to call out the sins of his “own” side, their decision shouldn’t be difficult.

Peter Beinart: Biden goes big without sounding like it

If unrest isn’t becoming a vulnerability for Biden, that’s because he has been so much more astute in avoiding Trump’s trap than the young and online. The latter have absorbed the preposterous lesson that to criticize riots (many of which are perpetrated by white political extremists) is to betray the movement for racial justice.

Far from being a source of weakness, the fact that Biden honed his political instincts over many decades is a source of electoral strength. And if Biden becomes the 46th president of the United States, it will not be despite his failure to understand (what most members of his own party believe to be) the spirit of the moment; it will be because he had the good political judgment to eschew it.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment