The Fourth of July Has Always Been Political

Is President Donald Trump politicizing the Fourth of July, allowing the crassness of partisanship to intrude on a sacred civic celebration? That widely posed question is built on a faulty premise. From the very beginning, Independence Day celebrations have been deeply political—in fact, the early celebrations were far more overtly political than today’s festivities. The right question isn’t whether July 4 is being politicized, but rather which vision of American citizenship it’s being used to advance.

In July 1776, American rebels staged celebrations of independence that were at once spontaneous and also—in a strikingly modern sense—media events. Independence had already been in the air for at least a year; the Continental Congress had already created public holidays, declaring two national days of fasting, on July 20, 1775, and May 17, 1776. Yet when it forwarded the printed Declaration of Independence to the states, Congress did not recommend fasting, prayer, bell ringing, or any other observance. Congress would not order the nation to celebrate its own birth. Instead, many colonists devised their own celebrations to mark the event.

The declaration had thrust all blame onto the king, and its public proclamation set off public, symbolic murders and funerals for the king—inversions of the King’s Birthday celebrations. People in New York City tore down the equestrian statue of George III and hacked it to pieces. (It is said that metal bits of it were later used to make bullets.) In other places, the monarch’s picture and royal arms were ceremoniously burned. In Savannah, Georgia, George III was “interred before the Court House.” The press descriptions made sure to mention the ringing of bells and the bonfires—the two most important aspects of traditional King’s Birthday celebrations. These printed descriptions inspired new celebrations and stressed the loud and visible support of the people for the end of monarchy and the beginning of American independence under new forms of government. The celebrations and descriptions they inspired made it seem possible that the 13 North American colonies, which until that time had more connections with England than with one another, might unite to form a new nation.

In Huntington, Long Island, people took down the old liberty pole and used the material to fashion an effigy. This mock king sported a wooden broadsword and was described in a newspaper as having a blackened face “like Dunmore’s Virginia regiment” (the enslaved people who had been invited by the governor of Virginia to help put down the rebellion) and feathers, “like Carleton and Johnson’s savages” (the king’s Iroquois allies in New York). Fully identified with his African and Indian allies, wrapped in the Union Jack, the king was hanged, exploded, and burned. Nation-building festivities in 1776 targeted a revealing array of enemies, a process that a seemingly depoliticized Fourth of July has helped us forget.

During the difficult years of the Revolutionary War, patriots began to celebrate the anniversary of American independence on July 4. They also marked battle victories, and their anniversaries. These patriots focused on what unified them and on the glorious national future they expected would follow from their victories, rather than on the British past that they had once actively remembered on such occasions. The revolutionary movement’s need to simultaneously practice politics and create national unity only raised the stakes of celebrating national holidays.

The trend in the early republic would be for July Fourth, and other celebrations modeled on the Fourth, to spread nationalism and, at the same time, to provide venues for divisive political expression. In this way, Americans learned both to be American and to practice partisanship without any sense of contradiction. Just as they blamed the British and their Native and African allies while drawing on British traditions, they used the Fourth of July to praise and criticize their governments and one another, in the process struggling over who, and what, was truly American.

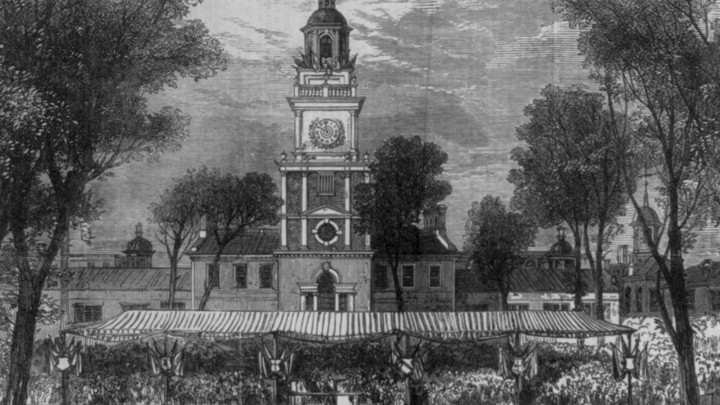

In 1787 and 1788, proponents of the new federal Constitution staged supposedly spontaneous celebrations of ratification in the various states, not only to express their relief, but also to attack their opponents and to try to convince doubters that the new national charter would inevitably be accepted by all the states. During the 1790s, when disputes over foreign affairs and the role of public opinion between elections led Federalists and Democratic Republicans to begin to coalesce into informal national political parties, these partisans began to hold separate Fourth of July celebrations in larger towns. They also used the Fourth and its now more fully developed repertoire of parades, sermons, toasts, and newspaper reportage as a model for new celebrations with explicit political meanings.

Federalists began to celebrate Washington’s Birthday in order to support Washington’s policies and to confirm their claims to embody the nation. For a time, Democratic Republicans marked anniversaries of the French Revolution, which they felt expressed the more democratic version of politics they sought to turn into American tradition. After 1800, they also celebrated March 4, the anniversary of Thomas Jefferson’s inauguration as president, as an alternative to what they called the “monarchical” tradition of Washington’s Birthday. Such celebrations helped Americans put into practice a two-party system, which few justified on its own terms but which, along with the newspapers that were increasingly subsidized by parties, provided an orderly meeting ground between an unwieldy federal electoral politics and a tradition of popular rituals.

July Fourth and its alternatives enabled Americans to preserve the paradox of revolutionary tradition. While these nationalistic political celebrations often came to have a conservative bent after the Revolutionary era, some, like the abolitionists, used the occasion to criticize American policy. Shut out of the two-party system by politicians who refused to address the issue of slavery on a national level, antislavery activists invented alternative festivals, such as celebrations of the end of the slave trade. When Frederick Douglass asked, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” and answered, “The Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn,” he did so at an alternative Fifth of July celebration held in Rochester, New York, in 1852. Douglass continued the American penchant for not only celebrating but also inventing new holidays when the political possibilities of the old ones seemed insufficient.

On this Fourth of July, we may be asking whether the president’s celebration, in which flyovers and tanks tell us that military service is the epitome of public service, is the right one. Or we may be asking, with Nike and Colin Kaepernick, whether we can see more in Betsy Ross’s flag than a proslavery emblem. But on any Fourth of July, the real question is what version of the republic we care to advance by celebrating.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

DAVID WALDSTREICHER is the distinguished professor of history at the Graduate Center at the City University of New York. He is the editor of The Diaries of John Quincy Adams 1779-1848.

No comments:

Post a Comment