The Problem With High-Minded Politics

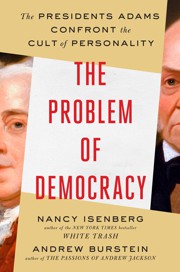

The Problem of Democracy: The Presidents Adams Confront the Cult of Personality VIKING

historians have not yet decided what to make of Donald Trump’s election, although some of us have been trying. Shortly before Trump’s inauguration, I participated in a session at the American Historical Association’s annual meeting devoted in part to assessing the president-elect in historical terms. The gathering had been planned much earlier, with Hillary Clinton’s presumed presidency in mind, so we speakers had to shift gears in a hurry. The best I could do was summarize Trump’s links to organized crime.

This article appears in the May 2019 issue.

Support 160 years of independent journalism. Starting at only $24.50. View more stories from the issue.

As it happens, my offhand remarks contained some foresight about public revelations in store, but they hardly explained Trump’s historical significance. Some scholars have reached for analogies, likening Trump’s victory to the overthrow of Reconstruction or to the excesses of the ensuing Gilded Age. Others have focused on the roots of Trump’s visceral appeal. Jill Lepore’s recent survey of American history, These Truths, describes Trump as buoyed by a new version of a conspiratorial populist tradition that dates back to the agrarian People’s Party of the 1890s. In a new dual biography of John Adams and John Quincy Adams, The Problem of Democracy: The Presidents Adams Confront the Cult of Personality, Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein trace Trump’s origins practically to the nation’s founding.

Not that Trump’s name ever appears in their book, but the connection is hard to miss. In a published symposium in 2017, Isenberg and Burstein, who both teach at Louisiana State University, in effect affirmed Trump’s bumptious self-identification with Andrew Jackson. It was not a compliment. They loathe Jackson as a savagely partisan demagogue who built on the dubious legacy of Thomas Jefferson, “tapped into the democratic id,” exploited popular resentment of the educated elite, and crafted a cult out of his own violent personality. Jackson, in short, was the “proto-Trump.”

The Problem of Democracy presents a corollary argument that by implication renders the Adamses—the presidents defeated by Jefferson and Jackson—historical anti-Trumps. Isenberg and Burstein complain that credulous historians have championed Jefferson and Jackson as the creators of “our mythic democracy”—in reality, they say, a sham democracy driven by personal ambition, partisan corruption, and shameless pandering that disguised the powerful interests truly in charge. The Adamses had the nerve to point out the chicanery of this racket, and for that, the authors argue, historians have dismissed them as out-of-touch, misanthropic stuffed shirts.

Isenberg and Burstein want to recover and vindicate what they describe as a lost “Adamsian” vision of a more elevated, virtuous, balanced, nonpartisan polity, so unlike the system that defeated them, the all-too-familiar forerunner of our own. By the Adamses’ standards, Trump is not an aberration. He is an exemplar of everything in our politics that they resisted in vain, especially the fraudulent party democracy that substitutes tribal loyalties and celebrity worship for informed debate.

But this view of the past and the present is flawed, historically as well as politically. The Adamses were chiefly the victims not of undeserving charlatans but of their own political ineptitude. And the crisis that has given us Donald Trump has arisen not from the excesses of a party politics the Adamses despised, but from the deterioration of the parties over recent decades. Trump, the celebrity anti-politician, exploited this decline ruthlessly, winning the White House through a hostile takeover of a badly shaken and divided Republican Party, which he has now transformed into his personal fiefdom.

Trump is not a creature of the party politics pioneered by Jefferson and Jackson. He is its antithesis, a would-be strongman who captured the presidency by demonizing party politics as a sham. He will be stopped only if the Democrats can mount a reinvigorated, disciplined party opposition. In that struggle, the Adamsian tradition is at best useless and at worst a harmful distraction.

isenberg and burstein greatly exaggerate the unpopularity of the Adamses among historians. Until Lin-Manuel Miranda rebranded the imperious Alexander Hamilton as a hip-hop immigrant superstar, no Founding Father (except perhaps George Washington) had been lionized by contemporary writers as much as John Adams, above all in David McCullough’s Pulitzer Prize–winning biography in 2001 and the HBO series that followed. No fewer than four admiring biographies of John Quincy Adams have appeared since 1997. In an era when the public’s regard for party politics has cratered—and a variety of independent candidates, from John Anderson and Ross Perot to Ralph Nader and Jill Stein, have played on this alienation—historians’ estimation of the anti-party Adamses has soared higher than ever.

The Problem of Democracy does add rich detail and insight to an established pro-Adams narrative about the politics of the early republic. The book’s chief contribution is to entwine the biographies of father and son, deepening our appreciation of their personal and political lives. It is not always a happy tale. John Adams, a self-made political striver, could in private be difficult to abide—a gloomy, often touchy man who, as Isenberg and Burstein neatly observe, “did not encounter the sublime in the world he traversed.” John Quincy Adams, born into public service, was raised to match severe paternal expectations. (In 1794, when he momentarily postponed any political ambition, his father told him that if he failed to reach the head of his country, “it will be owing to your own LazinessSlovenliness and Obstinacy.”) The son was afflicted all his life by what he called an “over-anxious” disposition that looks today like clinical depression. He nevertheless made it to the top of the heap—unlike his less fortunate younger brothers, Charles and Thomas, both of whom fell into hard drinking, and one of whom died young of alcoholism.

Despite the tension—or maybe because of it—John and John Quincy developed a singular bond, a convergence of temperament and intellect that was vital to both men. They shared a love of the classics, worshipping the philosophes’ favorite Roman, Cicero, who combined intense political activity and gravitas, his republicanism tempered by an aristocratic disdain for passion and disorder. They adhered to what Isenberg and Burstein call “the Adamsian credo,” blending probity, dignity, erudition, and honor. Although John Quincy acquired a Christian moralism unknown to his father, both men located the rising glory of America in its cultivation of intellectual excellence and disinterested virtue. All of which estranged them from the rough-and-tumble partisan politics that were emerging everywhere they looked. In time, they became men without a party, or more precisely, the members of a party of two.

Of all the elements of the lost Adamsian politics, disgust for political parties most attracts and animates Isenberg and Burstein. At the nation’s founding, they remind us, a mistrust of parties was widely shared. Americans feared that parties, once consolidated, would inhibit “the development of a national political morality,” elevate personal ambition, and wind up enshrining either dictatorship or oligarchy.

Such lofty ideals, though, could not withstand the clash of interests between Hamiltonian city dwellers and financiers and Jeffersonian country yeomen and slaveholders. Those opposing interests produced the prototypes for modern political parties—elite-controlled vote-gathering contraptions that flatter the masses, slander opponents, and secure loyalty with a combination of personality cults and patronage. Caught between the designs of Hamilton and Jefferson, the high-minded patriot John Adams was crushed in 1800. Nearly 30 years later—concluding a brief, one-party Era of Good Feelings—John Quincy Adams was overthrown by the demagogue slaveholder Jackson and his Democratic Party of loyal newspaper editors and wire-pullers. “Talk of democracy,” Isenberg and Burstein write, “was the smoke screen that hid the real engine behind party politics”: a thirst for material gain and imperial conquest, underwritten by the enslavement of blacks and the violent expropriation of Native Americans.

but these accounts of the Adams presidencies are skewed, mistaking the Adamses’ political naïveté and incompetence for independent virtue while eliding events that don’t conform to the authors’ own anti-party presumptions. John Adams, for example, began his presidency by retaining George Washington’s Cabinet, which included a knot of plotters under the sway of the intriguer Hamilton, who, now outside the government, was determined to manipulate the administration. The scheming of these Federalist presidential advisers helped maneuver Adams into actions Isenberg and Burstein sometimes acknowledge but downplay. He prepared to launch military operations against France. He approved Congress’s creation of a large land-defense force that turned into a politicized standing army under Hamilton’s control. He signed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which singled out immigrants and whipped up nativism while directly attacking freedom of the press.

By abetting what Jefferson called “the reign of witches,” the hapless Adams ensured that the Jeffersonians would contest his reelection. After detecting the machinations too late to regain command, he changed course, pursued peace with France, and dissolved the provisional army—only to be furiously denounced by Hamilton on the eve of the election in 1800. Adams left office dazed and embittered, inveighing against his supposed allies as well as lying newspaper editors. He was convinced that his defeat proved “we have no Americans in America.”

John Quincy Adams was a genuine visionary, with bold plans to enlarge the nation’s moral, scientific, educational, and commercial capacities. But he came to power through one of the greatest blunders in our political history, the so-called corrupt bargain. In the four-way presidential contest in 1824, Andrew Jackson claimed popular as well as Electoral College pluralities, yet Adams won the presidency in the House of Representatives thanks to the support of Jackson’s nemesis, Speaker of the House Henry Clay. Days later, Adams privately announced that he had offered Clay the job of secretary of state, the second-most-powerful executive post—a devastating example of how the appearance of corruption could be as damning as the real thing.

Fairly or not, the bargain branded Adams from the start as a conniving, illegitimate president, and thereafter, his tone-deaf rectitude continually undermined his presidency. He announced his daring program of federal improvements with a cringe-inducing slap at the electorate, urging Congress not to be “palsied by the will of our constituents.” He declined to use the political tools at his disposal, above all patronage, to shore up his support against the emerging Jacksonian opposition. When supporters of his failed reelection bid against Jackson in 1828 circulated scurrilous attacks on Jackson’s wife as well as on the candidate himself, Adams self-righteously denied any involvement in the slanders, offended even to be implicated.

Unlike his father, John Quincy Adams had a second act. He returned to Washington as a congressman and became a resourceful and implacable foe of the slave power and its efforts to gag debate about slavery in national politics. Yet Isenberg and Burstein ignore how Adams, upon reentering politics, became a self-described “zealous” adherent of the great populist movement of the day, the Anti-Masonic Party, which in time dissolved into the northern antislavery wing of the anti-Jacksonian Whig Party.

Although never a conventional party man, Adams belatedly learned how to deploy his talents within the party framework. He stirred up both popular and congressional opinion as Old Man Eloquent in the House, and plotted strategy with radical abolitionists as well as his antislavery House allies to overturn the gag rule. They finally achieved success in 1844. By the time Adams collapsed and died at the Capitol, four years later, he had helped pave the way for what would eventually become the Republican Party, the first antislavery party in history. The greatest leader of that party would be an admirer of Adams—the one-term Whig congressman Abraham Lincoln, a skilled and unapologetic party politician who happened to be on the floor of the House at the moment Adams crumpled.

after the civil war, disdain for the grubby operations of party politics produced a distinct antipartisan style, evident across the political spectrum. Through subsequent generations of Mugwumps, Progressives, numerous other good-government groups, and “new politics” insurgencies, antipartisanship abetted diverse crusades, united in the belief that, unshackled from party politics, enlightened democracy would thrive.

Ironically, the antipartisan style, wedded to some of the darker impulses of our political history, has culminated in Donald Trump’s presidency. In the long aftermath of the Vietnam War and Watergate, both major parties were battered from within, institutionally as well as ideologically. The Democrats, reeling from the traumas of the late 1960s, especially the violence at their national convention in 1968, deliberately reformed their national structure to reduce the power of party leaders. The result was to turn the party into competing interest groups lacking clear direction. The Republicans, commandeered after Watergate by the movement conservatives who championed Ronald Reagan, set in motion a process of radicalization personified by Newt Gingrich. The vanguard demonized government ever more stridently while it continually attacked a diminishing party establishment. Enter Trump, who promised to drain the swamp that the corrupt “loser” politicians had created and who vowed to put “America first,” above everything else, including party.

Other elements of Trump’s ascendancy invite historical analogies unflattering to the Adamses. With the Alien and Sedition Acts, for example, John Adams unheroically approved the exploitation of anti-immigrant nativism while persecuting and even jailing unfriendly newspaper editors as enemies of the people. His greatest act as president was to reverse course and put his reelection at risk once he recognized the nightmare his presidency was creating.

John Quincy Adams left two divergent legacies. One was of a farseeing president who disdained party politics, achieved little, and was ruined. The other, completed in an office far below the presidency, involved advancing a radical cause through cunning maneuvers and helping to inspire what became the Republican Party. Looking to 2020, the best high-minded alternative to Trump would appear to be Howard Schultz, the former CEO of the progressive Starbucks chain, who proclaims his anti-party virtue as well as his reasonable moderation. Tell that, though, to Trump’s truest and most effective foe, a daughter as well as a veteran of dishonored, hard-bitten party politics: Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi.

This article appears in the May 2019 print edition with the headline “The Problem With High-Minded Politics.”

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

SEAN WILENTZ teaches history at Princeton and is the author, most recently, of No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding.

No comments:

Post a Comment