POLITICS

Believe James Comey

I watched all of James Comey’s interviews. He’s telling the truth.

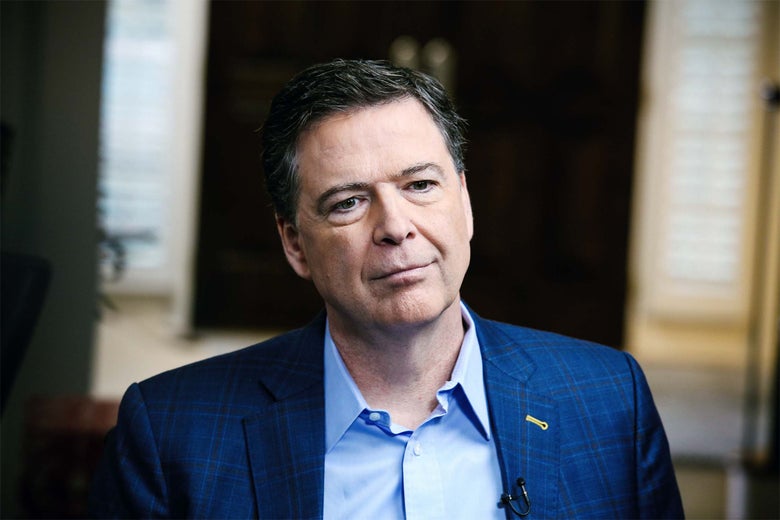

Former FBI Director James Comey sits down for his interview with George Stephanopoulos, which aired on April 15.

Ralph Alswang/ABC

According to the New York Times, special counsel Robert Mueller has four dozen questionshe wants to ask President Donald Trump about the Russia investigation. At least 18 of them focus on James Comey, the man Trump fired as FBI director last year in a failed attempt to “lift the cloud” of the investigation. Many of the questions involve meetings between Trump and Comey. Comey says Trump pressed him for personal loyalty and asked him to drop his investigation of then–National Security Adviser Mike Flynn. Trump denies it. It’s Trump’s word against Comey’s.

That’s why Trump has relentlessly attacked Comey’s credibility since he fired him. On Saturday night, at a rally in Michigan, Trump again called Comey “a liar and a leaker” for disclosing, in contemporaneous memos, the contents of their meetings. Trump mocked the interviews Comey has given in recent weeks about the former director’s new book, A Higher Loyalty. “Watch the way he lies,” said Trump.

By all means, watch Comey’s interviews. They’ll give you a chance to hear directly from the man whose testimony could put Trump away for obstruction of justice. We know Trump has a long record of fabrication and delusion. But what about Comey? How does he conduct himself when pressed to answer hard questions? To find out, I spent the past two weeks watching and listening to every available interview on Comey’s book tour, from the BBC to Sacramento, California, talk radio. Over the course of 19 interviews, I came away with two impressions. One, Comey is indefatigably earnest. I can see how he grates on people. And two, if I were a juror, I’d believe him. He’s telling the truth.

In the interviews, Comey gets grilled about physical depictions of Trump in his book—normal-size hands, ill-fitting ties—which come across as unflattering. The complaint is that Comey did this to get back at Trump for firing him. That’s a bum rap. Comey is just another policy guy trying, clumsily, to write descriptive prose. The better critique is that Comey is what Trump called him: a showboat. He gives press conferences when he shouldn’t, he writes a book, he hawks it with the stamina of a decathlete. I’ll grant you all that. But under interrogation, Comey’s answers, unlike Trump’s, are modest and reflective. His demeanor—eyes, voice, ease of response—shows no hint of dishonesty. Compared with Trump, he’s a far more credible witness.

Trump claims to know things he doesn’t know. Comey makes no such pretense. When he doesn’t know something, he says so. Did people connected to Trump collude with Russia? “I don’t know,” Comey told ABC’s George Stephanopoulos. Does Russia have something on Trump? “I don’t know,” Comey told USA Today’s Susan Page. Was Trump a crooked businessman? “I don’t want to talk about things I don’t know about,” Comey told the New Yorker’s David Remnick. Did Trump ask Mike Pompeo, who was then the CIA director, to pressure Comey last year to drop his investigation of Flynn? Comey demurs, saying he didn’t witness the conversation. How much Russia evidence remains secret? Comey demurs again, noting that in the year since he was fired, “It’s possible things that I ‘knew’ have changed.”

Trump casually attributes bad motives to Comey. Comey doesn’t reciprocate. Why won’t Trump criticize Russia? “I don’t know, and I’m not in a position to speculate,” Comey told a CNN town hall. Why did Trump keep telling Comey, when he was FBI director, that Trump hadn’t used prostitutes? “No idea,” Comey told MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow. When Trump pardoned former Bush aide Scooter Libby, was that a signal to Trump associates caught up in the Russia investigation? “I don’t know,” Trump told Page.

Trump attacks everyone connected to Comey. Comey doesn’t attack people connected to Trump. In the interviews, Comey rebuffs invitations to speculate about Attorney General Jeff Sessions and pro-Trump FBI agents. He defends Flynn—“Good people do lie, and my sense of Flynn was he was a good guy”—and refuses to criticize Flynn’s plea agreement. “I can’t see what’s on the other side of the wall—that is, what is the evidence, and what’s the nature of his cooperation,” Comey told NBC’s Chuck Todd.

Trump, armed with no evidence, accuses Comey of crimes. Comey, armed with lots of evidence, levels no such charges at Trump. Mueller “may conclude that there is nothing that touches President Trump or any of his senior people,” Comey told Stephanopoulos. “And that’s fine, so long as he’s able to find that truth.” When NPR’s Carrie Johnson and Steve Inskeep pressed Comey to say that Trump had obstructed justice, based on Comey’s memo about Trump asking him to drop the Flynn investigation on Feb. 14, 2017, Comey refused to bite:

Obstruction of justice requires a demonstration of corrupt intent. And I’m just a witness when it comes to that particular incident, the Feb. 14 incident. And so I don’t know what the evidence is that the prosecutor and investigators have gathered with respect to intent. … It would be an overreach for someone on my part to say, “I know what the evidence is.” How would I possibly know what the evidence is? I don’t know what communications President Trump’s staff were having with him. I don’t know what he said to others.

When Comey does venture an interpretation, he cautions that he might be mistaken. “I could be wrong,” he says. “This is speculation.” “This is just a guess.” “I might be misinterpreting it.”

Trump lauds himself and blames others. Comey criticizes himself and takes responsibility. He says he hedged too much about the Hillary Clinton email investigation, botched his announcement when he ended it, unwisely told Trump that he wasn’t under investigation, and failed to speak clearly to Trump about FBI independence. He calls himself “cowardly” for ducking, rather than challenging, Trump’s efforts to corrupt him. He accepts blame for anti-Trump texts written by two FBI employees without his knowledge: “I’m responsible for their actions and their poor judgment.” He welcomes a forthcoming report by the Justice Department’s inspector general: “Maybe they’ll criticize me. That’s OK. What I wanted was a full accounting of the decisions we made.”

Trump often repeats his mistakes because he doesn’t understand himself. Comey studies his own flaws, so he can correct them. “I could be reasoning poorly, I could be seeing facts poorly,” Comey told NPR. “I make mistakes all the time.” He confessed to Stephanopoulos: “My primary worry about myself is an overconfidence that can lead to … closed-mindedness. … I have to be careful not to fall in love with my own view of things.”

When Trump is accused of bias, he denies it and digs in. When Comey is accused of bias, he listens. At the CNN town hall, Comey urged the audience to “understand biases, cross-examine yourself.” To root out biases, he explained, you have to “bring them to consciousness.” In several interviews, Comey spoke of the now-infamous Oct. 27, 2016, letter in which he revealed his resumption of the Clinton email investigation. Comey said he hadn’t thought about polls when he decided to send the letter. But he conceded that the expectation of a Clinton victory must have affected him:

Stephanopoulos: Wasn’t the decision to reveal influenced by your assumption that Hillary Clinton was going to win? And your concern that she wins, this comes out several weeks later, and then that’s taken by her opponent as a sign that she’s an illegitimate presidentComey: It must have been. I don’t remember consciously thinking about that, but it must have been. ’Cause I was operating in a world where Hillary Clinton was going to beat Donald Trump … that she’s going to be elected president, and if I hide this from the American people, she’ll be illegitimate the moment she’s elected, the moment this comes out.

Trump surrounds himself with sycophants. Comey, mindful of his own biases, chooses advisers who are willing to correct him. He described to Remnick how his FBI team talked him out of publicly contrasting Clinton’s email practices with “gross negligence.” Comey told NPR: “I make mistakes all the time, which is why I worked hard to surround myself with people at the department and the FBI who would bang on me, who would talk to me, who would tell me what they thought.”

That’s why Comey has become a better person and leader than Trump. It’s why you should believe Comey’s account, not Trump’s, of what happened in their private meetings. At age 71, Trump is still a child. “I would give myself an A+,” he declared Thursday on Fox & Friends, when asked to assess his presidency. “Nobody has done what I’ve been able to do.”

Comey, meanwhile, has grown up. To become a good leader, he told Mike Allen of Axios on Monday, you have to “realize you’re not good enough, and the path to getting better is learning from other people.” Part of that, he explained to Stephanopoulos, “is just aging and getting to realize that doubt is not a weakness. Doubt is a strength.” Don’t trust the man who pretends he knows everything. Trust the man who admits he doesn’t.

One more thing

Since Donald Trump entered the White House, Slate has stepped up our politics coverage—bringing you news and opinion from writers like Jamelle Bouie and Dahlia Lithwick. We’re covering the administration’s immigration crackdown, the rollback of environmental protections, the efforts of the resistance, and more.

Our work is more urgent than ever and is reaching more readers—but online advertising revenues don’t fully cover our costs, and we don’t have print subscribers to help keep us afloat. So we need your help.

If you think Slate’s work matters, become a Slate Plus member. You’ll get exclusive members-only content and a suite of great benefits—and you’ll help secure Slate’s future.

No comments:

Post a Comment