The Civil War Was Not a Mistake

John Kelly’s account of its causes reflects a widely shared—and incorrect—understanding of the conflict.

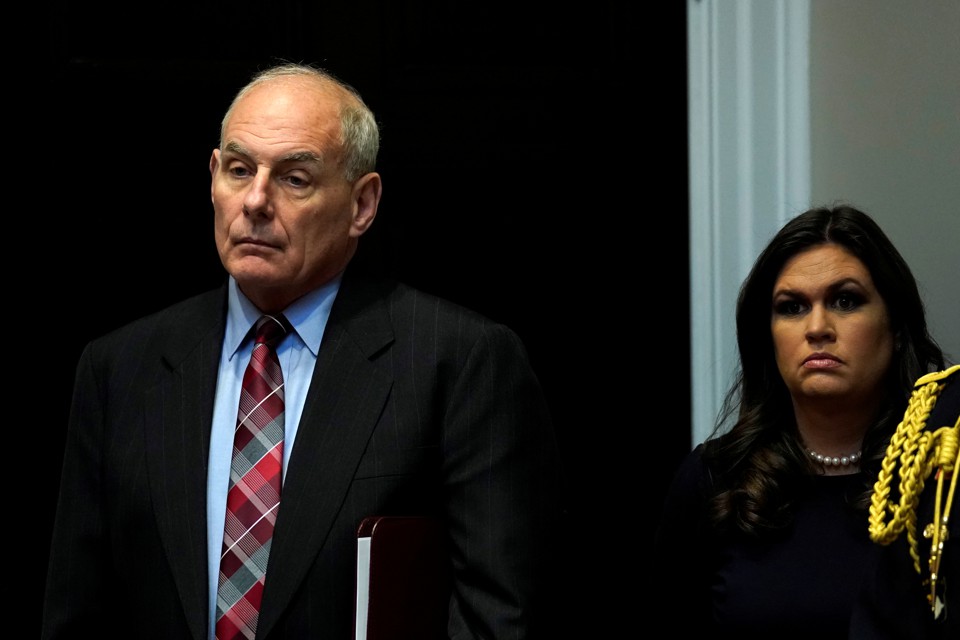

When White House Chief of Staff John Kelly told the Fox News host Laura Ingraham that the Civil War was caused by the “lack of an ability to compromise,” that the war was fought by “men and women of good faith on both sides,” and that Confederate General Robert E. Lee “was an honorable man,” he was invoking a rosy view of the Confederacy echoing that of his boss.

Kelly was also reflecting a popular perception of the war that has persisted for decades, largely on the strength and influence of an organized pro-Confederate propaganda campaign that has been conducted for a century. While the scholarly consensus is that the Civil War was about slavery, popular opinion has not entirely caught up. The Lost Cause campaign was so successful that perhaps the most widely seen piece of popular history related to the Civil War, Ken Burns’s 1990 PBS documentary of the same name, retains elements of its narrative.

“Basically, it was a failure on our part to find a way not to fight that war. It was because we failed to do the thing we really have a genius for, which is compromise,” the historian Shelby Foote says in Burns’s miniseries. “Americans like to think of themselves as uncompromising. But our true genius is for compromise. Our whole government’s founded on it. And it failed.” Burns’s documentary similarly describes Lee as a reluctant rebel and a “courtly, unknowable aristocrat, who disapproved of secession and slavery, yet went on to defend them both at the head of one of the greatest armies of all time.” In The Civil War, the companion book to the documentary co-authored by Burns, the documentary's co-writer Geoffrey Ward describes Lee as someone who "never owned a slave himself."* In truth Lee opposed neither slavery nor secession, and owned slaves he inherited from his father-in-law, whom he only freed under court order.

Foote is correct in a sense that Americans have a genius for compromise. As The New Yorker’s Jelani Cobb points out, the path to the Civil War was littered with compromises over slavery. In the Constitution itself, the Three-Fifths Compromise granted political power to the slave states, and the fugitive-slave clause enshrined owners’ rights to their human chattel. There was the Northwest Ordinance, which outlawed slavery in the Northwest Territory but contained a fugitive-slave clause; the Fugitive Slave Act; the Missouri Compromises; the House gag rule banning antislavery petitions; the Compromise of 1850; the Kansas–Nebraska Act, putting slavery to a popular vote within the territories; the unsuccessful Crittenden Compromise; and of course Abraham Lincoln’s own entreaties to the South to return to the Union with slavery itself intact. “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it,” Lincoln wrote to Horace Greeley in 1862, “and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.”

Lincoln would not be given the choice. But his letter makes clear that any compromise that could have been reached with the Southern states would have been a compromise over the personhood of black people—and, like all compromises before it, merely a delay of the inevitable conflict to come. The seceding states all noted the centrality of slavery in their declarations of secession, and Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens declared, “The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution—African slavery as it exists amongst us—the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization.” Slavery could persist, or the Union could persist, but ultimately they could not persist together. Only one of these causes was just.

As my colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates points out, Kelly’s insistence that “it’s inconceivable to me that you would take what we know now and apply it back then” is a blinkered view of history that regards only the opinions of white slave owners as relevant. Both the slaves and the hated white abolitionists, whose movement could not have existed otherwise, knew that slavery was wrong.

What is strange is that the circumstances surrounding the abolition of slavery and the preservation of the Union are regarded as tragic. The issues debated on the eve of the Revolutionary War were more amenable to compromise than those that rent the Union in two in 1861. Many Americans died in the Revolutionary War; neither the United States nor Great Britain today regards its outcome as lamentable. Few regret that George Washington and King George III didn’t sit down at a table and hash out a compromise. Almost no one wrings their hands today about the uncivil tone of the Boston Tea Party, or the colonists’ stubborn insistence on self-governance.

That the nation’s rebirth, in which the promises of its founding creed first began to be met in earnest, is regarded as sorrowful is a testament to the strength of the alternative history of the Lost Cause, in which the North was the aggressor and the South was motivated by the pursuit of freedom and not slavery. The persistence of this myth is in part a desire to avoid the unfathomable reality that half the country dedicated itself to the monstrous cause of human bondage. The freedom that the South fought for was the freedom to own black people as property. The states’ rights for which the South battled were the right to own slaves and the right to expand slavery.

Of course, the compromises did not end there. American reunion was preceded by the violent reimposition of white supremacy in the South, with the acquiescence of the North. The New Deal was shaped by compromises between Northern Democrats and Southern Democrats that limited many of its benefits to whites. Republicans broke with their own abolitionist history, bending to oppose civil rights in exchange for Southern votes. America compromised when it outlawed de jure segregation and sanctioned de facto segregation. Paring back the welfare state and building up the carceral state was a compromise. Offering body cameras in response to unarmed black people being gunned down by armed agents of the state with impunity is a compromise. This is a significantly abridged list; you can trace the entire history of the United States through political compromises in which black rights are the currency of exchange.

Kelly’s remarks, then, are part of an American tradition of historical denial, and he is hardly its only adherent. It is fair to ask, however, why Kelly believes that there could have been compromise over the issue of slavery, that a war over human bondage could have contained “men and women of good faith on both sides,” and that a man could have killed thousands of his countrymen and still be honorable, but that a Gold Star widow who feels disrespected by the president’s words, that a congresswoman who defended her and was slandered by Kelly himself, and that the athletes who refuse to compromise on the question of black personhood should be given no quarter.

No comments:

Post a Comment