What Would You Do If You Were a Presidential Elector?

The framers didn’t intend electors to act independently, but as individuals, they now face a difficult set of choices.

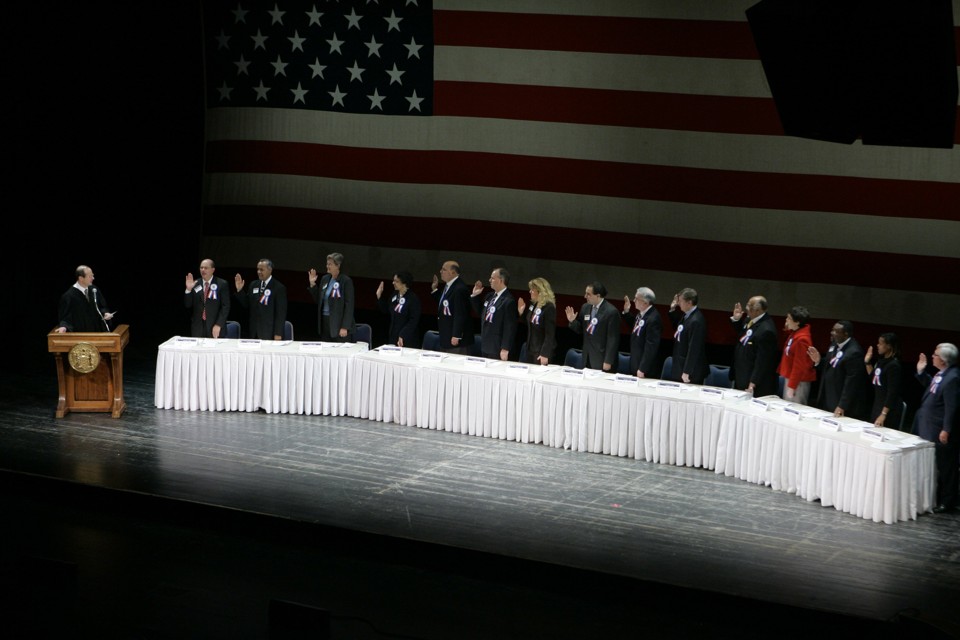

That’s especially true between now and Monday, December 19, the day the electors, gathering in the 50 state capitals and the District of Columbia, cast their votes for president.

As the reality of a Trump presidency hurtles toward the U.S., many of those Americans who opposed his election are turning to the college with the desperation described by W.H. Auden in Spain (1937):

Intervene. O descend as a dove orSurely the Electoral College will save them. Surely it is there to save them. Surely the all-seeing Founders created it to save them from an election like this one.

A furious papa or a mild engineer, but descend.

And most likely, December 19 will come and go, the biggest anti-climax since Y2K, with Trump’s electors meekly voting the expressed will of their state’s voters, giving him the majority he needs.

Should they? Advocates have advanced a few really bad reasons why they should not. Hillary Clinton’s thumping popular vote victory is a historic fact, but not a reason why electors would switch. I tend to doubt that Trump, no matter what campaign he ran, could have reversed Clinton’s current (and growing) margin of 2.8 million votes. But what you or I think probably doesn’t matter to a Republican who volunteered last summer to be a Trump elector. The aim of both campaigns was always to get 270 electoral votes, and Trump got them. Asking an elector to switch for that reason smacks of dishonesty.

And I don’t think the Founding Fathers somehow “intended” the electors to function in this situation as wise elders. If they did, I think the Electoral College would operate far differently. The electors never meet, they don’t debate, they vote only once, and they disappear. To me, that’s not a deliberative body; that’s a protection for states that choose to disfranchise their people. In Federalist 68, Hamilton makes a good case for the opposite interpretation; that essay reminds me of what my mother used to say about my late Uncle George’s Army stories—“They’re so good they make you wish they were true.”

As far as I am concerned, a system in which electors pretend to support one candidate and then go shopping their votes after the fact is dangerous. If you doubt that, consider the frank admission by former Republican vice-presidential nominee Bob Dole that, had the 1976 election been slightly closer, his party was “shopping—not shopping, excuse me. Looking around for electors … We needed to pick up three or four after Ohio.” Turning the post-election pre-vote period into a bidding war would be the one thing most calculated to make the electoral-vote system more of a disaster than it is.

On the other hand, there’s also nothing wrong with saying that on December 19, the electors chosen in November will be responsible for choosing the next president. Not the voters of their states, not the leaders of their parties.

They themselves. Their individual votes will determine the result.

And each of them must make his or her own choice.

Should an elector disregard a pledge because supporters of the other candidate offer consideration—even to the extent of offering to pay a state fine for violating the pledge? Of course not.

Should an elector disregard a pledge because—let’s say—facts emerge about a candidate between election day and the electoral vote that suggest that the candidate is unfit to serve?

That one is hard.

What if, to take a wild example, intelligence emerges to the effect that the electoral-vote winner, a popular-vote loser, was aided to victory by the spy service of a foreign dictatorship with a foreign policy hostile to the nation’s best interests? What if that candidate refused even to discuss the intelligence, and attacked the U.S. government instead of demanding an investigation? What if that candidate gave every evidence of eagerness to discredit his own country’s intelligence service rather than allow the public to know some as yet undisclosed facts about himself and his campaign?

Imagine you were an elector. Imagine you had promised to support a candidate whose platform was American greatness. And imagine before your vote—the vote that would count for history, the vote that could never be recounted or taken back—you received evidence suggesting that the candidate was unfit for the office that he seeks?

And imagine that he wouldn’t do anything to dispel suspicion or refute the evidence.

Don’t look at the popular-vote tracker. Don’t look at the “Founding Fathers.” This is a new problem, and the only place to look is your own conscience.

What woul

No comments:

Post a Comment