SUNDAY, SEP 27, 2015 10:59 AM CDT

Ronald Reagan’s “welfare queen” myth: How the Gipper kickstarted the war on the working poor

Some 1.5 million households live on less than $2 a day. Welfare would help, but it's gone -- and this is why

Excerpted from "$2 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America"

Welfare’s virtual extinction has gone all but unnoticed by the American public and the press. But also unnoticed by many has been the expansion of other types of help for the poor. Thanks in part to changes made by the George W. Bush administration, more poor individuals claim SNAP than ever before. The State Children’s Health Insurance Program (now called CHIP, minus the “State”) was created in 1997 to expand the availability of public health insurance to millions of lower-income children. More recently, the Affordable Care Act has made health care coverage even more accessible to lower-income adults with and without children.

Perhaps most important, a system of tax credits aimed at the working poor, especially those with dependent children, has grown considerably. The most important of these is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The EITC is refundable, which means that if the amount for which low-income workers are eligible is more than they owe in taxes, they will get a refund for the difference. Low-income working parents often get tax refunds that are far greater than the income taxes withheld from their paychecks during the year. These tax credits provide a significant income boost to low-income parents working a formal job (parents are not eligible if they’re working off the books). Because tax credits like the EITC are viewed by many as being pro-work, they have long enjoyed support from Democrats and Republicans alike. But here’s the catch: only those who are working can claim them.

These expansions of aid for the working poor mean that even after a watershed welfare reform, we, as a country, aren’t spending less on poor families than we once did. In fact, we now spend much more. Yet for all this spending, these programs, except for SNAP, have offered little to help two people like Modonna and Brianna during their roughest spells, when Modonna has had no work.

To see clearly who the winners and losers are in the new regime, compare Modonna’s situation before and after she lost her job. In 2009, the last year she was employed, her cashier’s salary was probably about $17,500. After taxes, her monthly paycheck would have totaled around $1,325. While she would not have qualified for a penny of welfare, at tax time she could have claimed a refund of about $3,800, all due to refundable tax credits (of course, her employer still would have withheld FICA taxes for Social Security and Medicare, so her income wasn’t totally tax-free). She also would have been entitled to around $160 each month in SNAP benefits. Taken together, the cash and food aid she could have claimed, even when working full-time, would have been in the range of $5,700 per year. The federal government was providing Modonna with a 36 percent pay raise to supplement her low earnings.

Now, having lost her job and exhausted her unemployment insurance, Modonna gets nothing from the government at tax time. Despite her dire situation, she can’t get any help with housing costs. So many people are on the waiting list for housing assistance in Chicago that no new applications are being accepted. The only safety net program available to her at present is SNAP, which went from about $160 to $367 a month when her earnings fell to zero. But that difference doesn’t make up for Modonna’s lost wages. Not to mention the fact that SNAP is meant to be used only to purchase food, not to pay the rent, keep the utility company happy, or purchase school supplies. Thus, as Modonna’s earnings fell from $17,500 to nothing, the annual cash and food stamps she could claim from the government also fell, from $5,700 to $4,400.

Welfare pre-1996 style might have provided a lifeline for Modonna as she frantically searched for another job. A welfare check might have kept her and her daughter in their little studio apartment, where they could keep their things, sleep in their own beds, take showers, and prepare meals. It might have made looking for a job easier —paying for a bus pass or a new outfit or hairdo that could help her compete with the many others applying for the same job.

But welfare is dead. They just aren’t giving it out anymore.

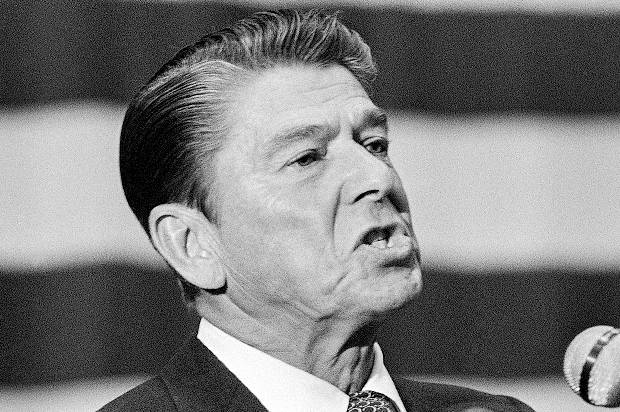

Who killed welfare? You might say that it all started with a charismatic presidential candidate hailing from a state far from Washington, D.C., running during a time of immense change for the country. There was no doubt he had a way with people. It was in the smoothness of his voice and the way he could lock on to someone, even over the TV. Still, he needed an issue that would capture people’s attention. He needed something with curb appeal.

In 1976, Ronald Reagan was trying to oust a sitting president in his own party, a none-too-easy task. As he refined his stump speech, he tested out a theme that had worked well when he ran for governor of California and found that it resonated with audiences all across the country: It was time to reform welfare. Over the years, America had expanded its hodgepodge system of programs for the poor again and again. In Reagan’s time, the system was built around Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), the cash assistance program that was first authorized in 1935, during the depths of the Great Depression. This program offered cash to those who could prove their economic need and demanded little in return. It had no time limits and no mandate that recipients get a job or prove that they were unable to work. As its caseload grew over the years, AFDC came to be viewed by many as a program that rewarded indolence. And by supporting single mothers, it seemed to condone nonmarital childbearing. Perhaps the real question is not why welfare died, but why a program at such odds with American values had lasted as long as it did.

In fact, welfare’s birth was a bit of a historical accident. After the Civil War, which had produced a generation of young widowed mothers, many states stepped in with “mother’s aid” programs, which helped widows care for their children in their own homes rather than placing them in orphanages. But during the Great Depression, state coffers ran dry. Aid to Dependent Children (ADC), as the program was first called, was the federal government’s solution to the crisis. Like the earlier state programs, it was based on the assumption that it was best for a widowed mother to raise her children at home. In the grand scheme of things, ADC was a minor footnote in America’s big bang of social welfare legislation in 1935 that created Social Security for the elderly, unemployment insurance for those who lost their jobs through no fault of their own, and other programs to support the needy aged and blind. Its architects saw ADC as a stopgap measure, believing that once male breadwinners began paying in to Social Security, their widows would later be able to claim their deceased husbands’ benefits.

Yet ADC didn’t shrink over the years; it grew. The federal government slowly began to loosen eligibility restrictions, and a caseload of a few hundred thousand recipients in the late 1930s had expanded to 3.6 million by 1962. Widowed mothers did move on to Social Security. But other single mothers —divorcées and women who had never been married —began to use the program at greater rates. There was wide variation in the amount of support offered across the states. In those with large black populations, such as Mississippi and Alabama, single mothers got nickels and dimes on the dollar of what was provided in largely white states, such as Massachusetts and Minnesota. And since the American public deemed divorced or never-married mothers less deserving than widows, many states initiated practices intended to keep them off the rolls.

Poverty rose to the top of the public agenda in the 1960s, in part spurred by the publication of Michael Harrington’s The Other America: Poverty in the United States. Harrington’s 1962 book made a claim that shocked the nation at a time when it was experiencing a period of unprecedented affluence: based on the best available evidence, between 40 million and 50 million Americans—20 to 25 percent of the nation’s population—still lived in poverty, suffering from “inadequate housing, medicine, food, and opportunity.” Shedding light on the lives of the poor from New York to Appalachia to the Deep South, Harrington’s book asked how it was possible that so much poverty existed in a land of such prosperity. It challenged the country to ask what it was prepared to do about it.

Prompted in part by the strong public reaction to The Other America, and just weeks after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, President Lyndon Johnson declared an “unconditional war on poverty in America.” In his 1964 State of the Union address, Johnson lamented that “many Americans live on the outskirts of hope —some because of their poverty, and some because of their color, and all too many because of both.” He charged the country with a new task: to uplift the poor, “to help replace their despair with opportunity.” This at a time when the federal government didn’t yet have an official way to measure whether someone was poor.

In his efforts to raise awareness about poverty in America, Johnson launched a series of “poverty tours” via Air Force One, heading to places such as Martin County, Kentucky, where he visited with struggling families and highlighted the plight of the Appalachian poor, whose jobs in the coal mines were rapidly disappearing. A few years later, as Robert F. Kennedy contemplated a run for the presidency, he toured California’s San Joaquin Valley, the Mississippi Delta, and Appalachia to see whether the initial rollout of the War on Poverty programs had made any difference in the human suffering felt there.

RFK’s tours were organized in part by his Harvard-educated aide Peter Edelman. (Edelman met his future wife, Marian Wright —later founder of the Children’s Defense Fund—on the Mississippi Delta tour. “She was really smart, and really good-looking,” he later wrote of the event.) Dressed in a dark suit and wearing thick, black-framed glasses, Edelman worked with others on Kennedy’s staff and local officials to schedule visits with families and organize community hearings. In eastern Kentucky, RFK held meetings in such small towns as Whitesburg and Fleming-Neon. Neither Edelman nor anyone else involved anticipated the keen interest in the eastern Kentucky trip among members of the press, who were waiting to hear whether Kennedy would run for president. Since the organizers had not secured a bus for the press pool, reporters covering the trip were forced to rent their own vehicles and formed a caravan that spanned thirty or forty cars. Edelman remembers that “by the end of the first day we were three hours behind schedule.”

No comments:

Post a Comment