The Party of Andrew Jackson vs. the Party of Obama

Seven years ago, as Obama methodically sewed up the Democratic Party’s nomination, the peculiar and unprecedented makeup of his voting base raised skepticism and even alarm. Minorities and college-educated whites thrilled to the young, black law professor, but working-class whites regarded him with suspicion and even hatred, continuing to vote for Hillary Clinton in overwhelming numbers even after her prospects of winning the nomination had disappeared. The conservative electoral analyst Michael Barone marveled at “Obama's great weakness among Appalachian voters — call them Jacksonians, after their first president.” Sean Wilentz, a Princeton supporter and staunch Clinton backer, complained that Obama was “usurping the historic Democratic Party, dating back to the age of Andrew Jackson, by rejecting its historic electoral core: white workers and rural dwellers in the Middle Atlantic and border states. … Out with the Democratic Party of Jefferson, Jackson, F.D.R., Truman, Kennedy and Johnson, and in with the bright, shiny party of Obama.”

But the transformation of the Democratic Party is not just the accidental byproduct of the current president’s identity. The party of Obama, and now the party of Clinton, is not a usurpation of a long American tradition but its fulfillment. Indeed, the premise that there is a philosophical tradition connecting Jackson to such figures as Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson — the cherished foundation of generations of Democratic Party thought — should be seen for what it is: a myth.

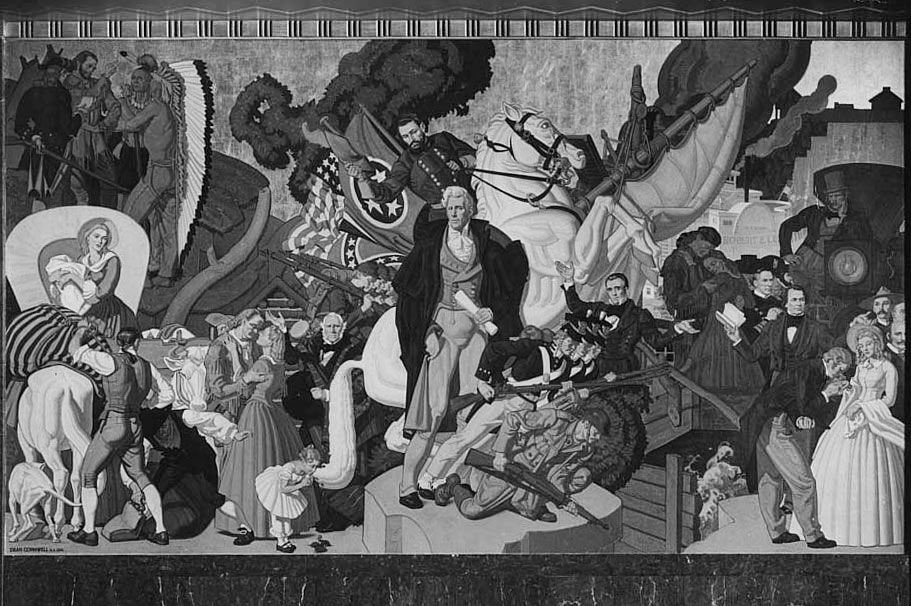

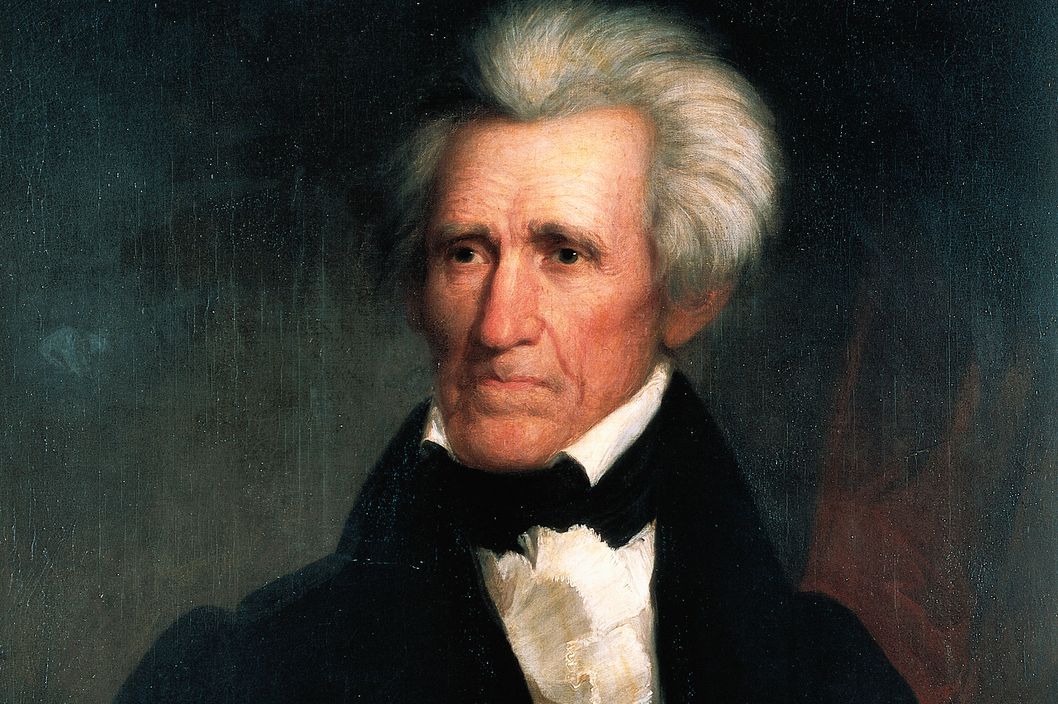

Jackson built a career as a war hero (or, alternatively, war criminal) and subsequent president from 1829 to 1837. His reputation as a populist, and therefore, as the progenitor of the Democratic Party, rests largely upon his successful fight to destroy the Bank of the United States, which was an early version of the Federal Reserve. “The rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes,” he wrote in his veto message, framing himself as the tribune of the common man in a way that helped make him the dominant figure of an era that stretched beyond his own presidency. To this day, nearly all state Democratic parties celebrate their history every year at “Jefferson-Jackson Day” dinners.

In 1945, the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., just 28 years old, published The Age of Jackson. In it, he presented Jackson’s ideas as “restrain[ing] the power of the business community,” which he called “the basic meaning of American liberalism.” Schlesinger worked closely with Democrats in Washington, later working for the Kennedy administration. His analysis created a kind of official party history, in which Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson led inevitably to the triumph of the dominant figure of Schlesinger’s day, Franklin Roosevelt.

The actual Jackson bears virtually no resemblance to the myth. Evolving social standards have complicated the uncritical celebration of any 18th- or 19th-century American leaders. But the problems with the celebration (and especially the liberal celebration) of Jackson go well beyond the fact that he owned slaves and persecuted Native Americans. Even by the standards of his day, Jackson displayed a notable passion for the institution of slavery, going so far as to prevent the distribution of abolitionist literature in the South. His administration’s central policy aim was the ethnic cleansing of large segments of the American South, driving out their native inhabitants for white settlement. Jacksonland, Steve Inskeep’s new history of the period, reveals that Jackson and his cronies personally grew rich from the policy of land expropriation that formed the core of his agenda.

Downplaying or ignoring Jackson’s conservatism, while conjuring a liberal ideology on his behalf, served a partisan interest for 20th-century Democrats. But there are also honest reasons that may have led historians like Schlesinger astray. From the standpoint of the 20th century, the United States had evolved into a two-party system in which the more liberal of the two parties had its strongest base in the Deep South. As this felt to many to be the inevitable direction of American politics, it seemed natural to peer back at the 19th century and see those coalitions in protean form. Despite its conservative views on race and suspicion of Washington, the white South probably appeared like a plausible base for the development of a liberal party.

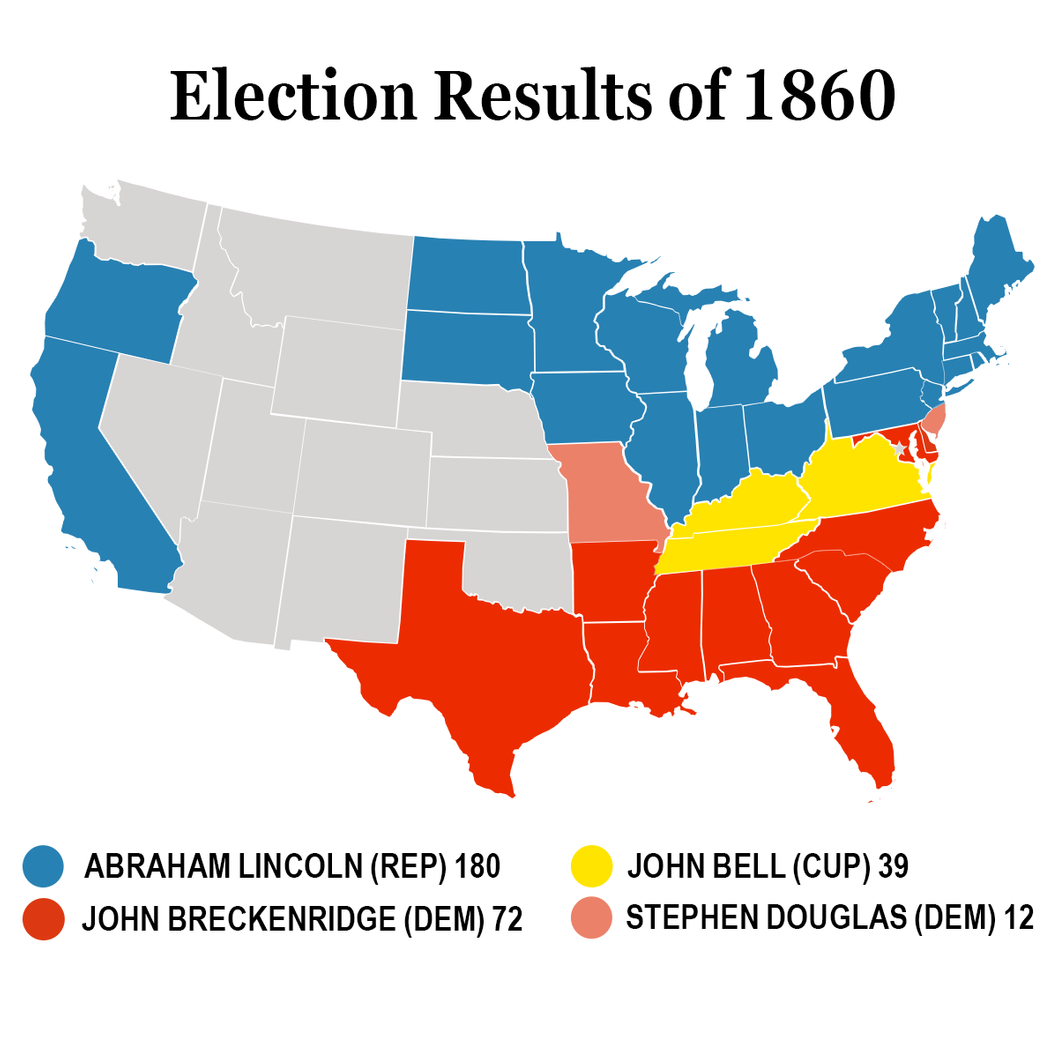

From the standpoint of the 21st century, things look very different. That the party of Andrew Jackson developed into the champion of civil rights and a strong centralized government looks like a bizarre accident that was bound to collapse. That even a few decades ago, avowed white supremacists and civil-rights activists shared a party now beggars belief. The political map of 21st-century America looks almost nothing like the 20th-century map. Instead it resembles the 19th-century map, with the party names simply reversed.

Jackson was a populist, but he directed his populism not at the local elites (of which he was one) but at the federal government. He favored the gold standard, and his opposition to a National Bank served the interests of the local banks that competed against it. He believed the Constitution prevented the government from taking an active role in managing economic affairs. He was instinctively aggressive, poorly educated, anti-intellectual, and suspicious of bureaucrats. (Jackson replaced more qualified federal staffers with partisan hacks.) He resisted any challenge to racial hierarchies. The opposition to Jackson stood for the reverse — a more interventionist federal government, more lenient treatment of racial minorities, a less aggressive foreign policy.

The qualities of the right-wing opposition during the Obama era has made the historic reversal all the more clear. Republicans have revived what they call “Constitutional conservatism,” which reprises the Jacksonian belief that the Constitution prevents economic intervention by the government. Tea-party activists in particular have sounded deeply Jacksonian themes in their populist attacks on TARP, and then Obama’s programs, as giveaways to powerful insiders. As a writer for the right-wing Breitbart News argued several months ago, “Jackson’s views on federalism and economics should be more carefully studied today.”

This combination of views on the Constitution, race, activist government, intellectual elites, and foreign policy all clump together geographically and ideologically. They also share a certain personality style — Jackson’s visceral style anticipates figures like George W. Bush and Sarah Palin. As the political fault lines of Rooseveltian America have grown increasingly distant in recent years, those of Jacksonian America have grown more recognizable. American history is returning full circle.

It was only a dozen years ago that Howard Dean, of all people, blurted out that his party could not win without the votes of “guys with Confederate flags in their pickup trucks.” In this polarized era, it would be an exaggeration to paint the intra-party opposition to Obama as heated or intense. The disagreements (in both parties) are relatively minor and centered around political tactics. The dissent to Obama within the Democratic party most frequently castigates him as too professorial, too alienated from the white working class, insufficiently populist — that is, too un-Jacksonian. Democratic former Senator Jim Webb has called on the party to “return to its Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Andrew Jackson roots.” Just a few weeks ago, historian David Greenberg defended Jackson’s populism. “One wonders whether the failure of Jackson’s detractors today to credit his democratic contributions,” he wrote, “isn’t related to the Democratic Party’s troubles in retaining the loyalty of white working-class voters.”

The relation is real. Jackson’s increasingly dismal historical reputation tracks the inevitable collapse of his vestigial partisan tradition. Modern Democrats increasingly look upon Jackson with revulsion, and if he could return to see what his party has become, he would reciprocate.

1 comment:

Glad if he's replaced on our currency. I've had enough of Jackson.

Post a Comment