Why History Will Be Very Kind to Obama

The Obama History Project

History Will Be Very Kind

By Jonathan ChaitHistory Will Eviscerate Him

By Christopher CaldwellHistorians Weigh In on Obama

The 53 Complete Questionnaires

Our National Affairs columnist:

History Will Be Very Kind

And if it's not, it will be for a highly ironic reason.

Photograph courtesy of the White House

The lived reality of Obama’s presidency has unfolded as almost the precise opposite of this trope. He has amassed a record of policy accomplishment far deeper than even many of his supporters give him credit for. He has also survived a dismal, and frequently terrifying, 72 months when at every moment, to go by the day-to-day media, a crisis has threatened to rock his presidency to its core. The episodes have been all-consuming: the BP oil spill, swine flu, the Christmas underwear bomber, the IRS scandal, the healthcare.org launch, the border crisis, Benghazi. Depending on how you count, upwards of 19 events have been described as “Obama’s Katrina.”

Obama’s response to these crises—or, you could say, his method of leadership—has been surprisingly consistent. He has a legendarily, almost fanatically placid temperament. He has now spent eight years, counting from the start of his first presidential campaign, keeping his head while others were losing theirs, and avoiding rhetorical overreach at the risk of underreach. A few months ago, the crisis was the Ebola outbreak, and Obama faced a familiar criticism: He had botched the putatively crucial “performative” aspects of his job. “Six years in,” BusinessWeek reported, “it’s clear that Obama’s presidency is largely about adhering to intellectual rigor—regardless of the public’s emotional needs.”

By year’s end, the death count of those who contracted Ebola in the United States was zero, and the panic appears as unlikely to define Obama’s presidency as most of the other crises that have come and gone. But there have been other times when Obama’s uninterest in engaging in the more public aspects of his job—communicating his reasoning and vision, soothing our anxieties with lofty rhetoric, infusing his administration with the sense of purpose that electrified his supporters during the 2008 campaign—has clearly harmed him. “If there’s one thing that I regret this year,” he admitted in 2010, “it is that we were so busy just getting stuff done and dealing with the immediate crises that were in front of us that I think we lost some of that sense of speaking directly to the American people about what their core values are.”

The president’s infuriating serenity, his inclination to play Spock even when the country wants a Captain Kirk, makes him an unusual kind of leader. But it is obvious why Obama behaves this way: He is very confident in his idea of how history works and how, once the dust settles, he will be judged. For Obama, the long run has been a source of comfort from the outset. He has quoted King’s dictum about the arc of the moral universe eventually bending toward justice, and he has said that “at the end of the day, we’re part of a long-running story. We just try to get our paragraph right.” To his critics, Obama is unable to attend to the theatrical duties of his office because he lacks a bedrock emotional connection with America. It seems more likely that he is simply unwilling to: that he is conducting his presidency on the assumption that his place in historical memory will be defined by a tabulation of his successes minus his failures. And that tomorrow’s historians will be more rational and forgiving than today’s political commentators.

It is my view that history will be very generous with Barack Obama, who has compiled a broad record of accomplishment through three-quarters of his presidency. But if it isn’t, it will be for a highly ironic reason: Our historical memory tends to romance, too. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fatherly reassurance, a youthful Kennedy tossing footballs on the White House lawn, Reagan on horseback—the craving for emotional sustenance and satisfying drama runs deep. Though the parade of Obama’s Katrinas will all be (and mostly already have been) consigned to the forgotten afterlife of cable-news ephemera, it is not yet certain whether this president can bind his achievements into any heroic narrative.

It is already clear that, whatever the source of the current disappointment with Obama, the explanation cannot be that he failed to achieve his stated goals. In his first inaugural address, Obama outlined a sweeping domestic agenda. The list of promises was specific: not only to rescue the economy from catastrophe but also to undertake sweeping long-term reforms in health care, education, energy, and financial regulation.

At first, conservatives denounced this agenda as a virtual revolution. “An ambitious president intends to enact the most radical agenda of social transformation seen in our lifetime,” cried the columnist Charles Krauthammer. It “would permanently refashion the role of the federal government in the lives of every American,” warned Jennifer Rubin. Conservatives have since changed their line, and now portray the president as a Carter-esque mediocrity—a “parenthesis in American political history” (Krauthammer) “with no significant accomplishment” (Rubin). But this is not because Obama failed to accomplish the goals he set out. On the contrary, he has incontrovertibly made major progress on, or fulfilled, every one of them. The horrifying consequences conservatives insisted would follow have all failed to materialize.

When Obama’s economic advisers set out to rescue the economy from the abyss, they did not realize how deep it ran. Preliminary measurements of the economic contraction, made at the end of 2008, turned out far too optimistic; as a result, the scale of the remedy they proposed did not meet the need. Still, the combination of rescue measures—an $800 billion economic stimulus, a bank rescue, and an auto bailout—could be historically matched in scale only by Franklin Roosevelt.

By any contemporary standard, the rescue succeeded. Of the 12 countries whose financial systems succumbed to the meltdown of 2008, the U.S. has grown economically at a faster rate than ten. (And the fastest, Germany, is currently teetering precariously.) Unemployment has fallen below 6 percent, and the United States is the locomotive of the world economy.

To be sure, the contemporary standard was fairly horrific. The developed world has suffered six years of economic pain, a fact that has dominated the political discourse. Obama’s Republican opponents have assailed his economic response, which they claim (contrary to the beliefs of more than 90% of professional economists) worsened the crisis. Even Obama’s allies have devoted more attention to the shortcomings of his rescue efforts than the virtues, in part because they sought to focus Washington’s attention on the plight of the unemployed. Paul Krugman devoted much of Obama’s first term to flaying the inadequacy of the administration’s fiscal response, and its failure to nationalize the large banks. Former New Republic economic reporter Noam Scheiber’s deeply reported history of the rescue, “Escape Artists,” emphasized its shortcomings rather than the huge amount of good it did. Liberal economic thought during the Obama years has, for perfectly rational reasons, been dominated by relentlessly campaigning against complacency rather than celebration.

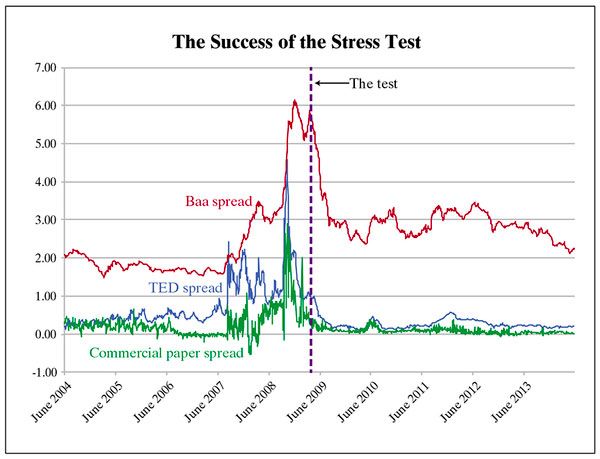

But it can be simultaneously argued that we have endured brutal deprivation and that Americans experienced the world’s most impressive recovery from the Great Recession. History is already being revised. In recent months, as the American economy has surged, Krugman conceded that the bank rescue plan designed by Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner worked after all (“He was right; I was wrong,” Krugman wrote in a New York Review of Books essay.) Scheiber recently allowed, “my verdict on the administration was overly harsh.” Geithner’s stress tests reduced the “spread” demanded by investors, which reflects the market’s measure of the failure risk, which plummeted immediately and permanently.

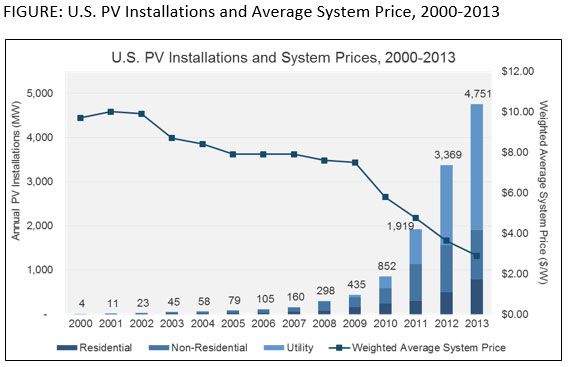

With hindsight, this will look smart. The stimulus act itself spurred 45 states to undertake reforms to their education systems. It prompted doctors and hospitals to shift to electronic medical records and provided $90 billion in funding for green energy sources. The portion of the stimulus that lent capital to unproven clean energy firms came under withering assault from Republicans, who relentlessly touted the failure of Solyndra, one firm that received loans. Surely this will recede in the collective memory now that the program is projected to earn taxpayers a net $5 billion. Thanks to public investment in the U.S. and abroad, solar energy has undergone revolutionary growth. Capacity has increased130-fold since Obama took office, while the price of installing a system has fallen by more than half.

But Obama discovered that existing regulations allowed him to accomplish the same goals to which his failed legislation aspired. In his second term, he unveiled strict new standards for automobile efficiency and power plant emissions that, taken together, allow the United States to meet its internal targets for carbon emissions. He reached a major climate agreement with China, which presages the first-ever international agreement by industrialized and developing countries alike to curtail their emissions (an agreement made easier by the revolutionary improvements in green energy, which could allow developing economies to leapfrog straight past the dirty energy stage). The success of this agreement will take decades to measure, but it could well go down in history as Obama’s most significant legacy.

Overall, Obama’s federal government powerfully reordered the most irrational and damaging aspects of the untrammeled marketplace without impairing its entrepreneurial vigor. He is neither the socialist his conservative enemies have called him nor the weakling his critics on the left have painted him to be. The administration’s financial reforms did not smash Wall Street, but they did reshape it and eliminate its worst abuses. A little-noticed law, passed in 2009, banned a host of abusive practices used by credit-card companies to bilk customers with late fees and hidden rate hikes. A year after passage, total late fees had fallen nearly in half.

The Dodd-Frank reforms went much further, attacking the failures that led to the meltdown from a variety of angles. Banks now must hold more capital, derivatives must be traded openly on exchanges, large institutions must separate their riskiest forms of trading, and any too-big-to-fail institution must create an advance plan for systemic failure. The law also created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, devised by Elizabeth Warren, which protects customers from financial industry abuses in much the same way as the Food and Drug Administration ensures the safety of our food.

News of the law’s impact has not filtered out to the broader public, but people who study the industry for a living have little doubt as to its impact. It is “altering Wall Street in fundamental ways,” The Wall Street Journal reported last summer. “There is no question that many of the highest-risk activities, which happened to be the most profitable activities for Wall Street, are now at least reduced and often totally gone,” Dennis Kelleher, a sharp critic of the industry, said recently. After slightly favoring Obama in 2008, Wall Street has now donated overwhelmingly to the Republican Party, which has staunchly promised to scrap Dodd-Frank.

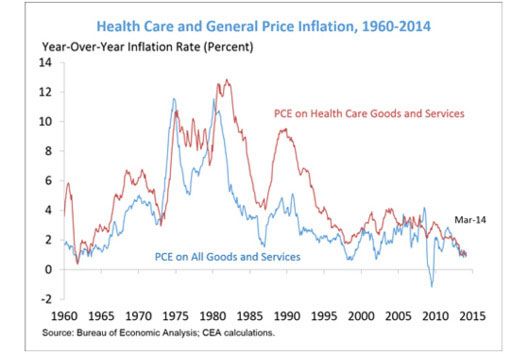

The Affordable Care Act enjoys—or suffers—a much greater public profile. The law set out to reverse the two unique features of the American health care system: it is the most expensive in the world by far, and the only advanced health care system without a universal right of access. By every important measure, it is succeeding at both goals. The number of uninsured Americans fell by ten million in the laws first year, and continues to drop as more people enroll. Republicans continue to boycott participation at the state level, but Republican-led states have slowly yielded to pragmatism, with Tennessee and Utah joining most recently. Health care premium inflation has fallen to historic lows. Obamacare’s various incentives to encourage hospitals, doctors and insurers to eliminate waste, in place for four years now, have yielded the lowest rate of medical inflation on record.

It is possible that Obama’s vigorous and creative exertions of executive authority in his second term, especially in reshaping immigration-law enforcement, might set a precedent for an excessively powerful presidency that Americans eventually come to regret. It is also surely true that many things were handled poorly, from his allowing Republicans to blackmail him with a debt-ceiling threat in 2011 to the botched launch of healthcare.gov. What cannot be questioned is the administration’s effectiveness, to date, at carrying out the tasks Obama identified at the outset. His administration has made the United States dramatically more prosperous, more egalitarian, and more sustainable. In a remarkable reversal from his predecessor, he has made the government functional and placed it on the side of those who most need its help.

In private conversation, Obama expresses frequent irritation with the news media’s hyperbole and lack of historical perspective. This habit has itself subjected him to withering criticism from Maureen Dowd, who has scolded, “the American president should not perpetually use the word ‘eventually.’ And he should not set a tone of resignation with references to this being a relay race and say he’s willing to take ‘a quarter of a loaf or half a loaf,’ and muse that things may not come ‘to full fruition on your timetable.’” Obama had also likened his foreign policy approach to hitting singles and doubles, further dissatisfying Dowd who, writing last April, brought up the existential crisis of the moment. “Especially now that we have this scary World War III vibe with the Russians,” she wrote, “we expect the president, especially one who ran as Babe Ruth, to hit home runs.” The World War III vibe has disappeared. Indeed, Russia blundered itself into a catastrophe. But attention has moved on. The widespread disappointment with Obama—“I’ve been asked the same question in Beijing, Auckland and Rome: ‘What happened to Barack Obama?,’” reported Howard Fineman last fall—reflects the reality that most of Obama’s presidency has actually felt terrible.

Chuck Todd’s new account of this presidency, The Stranger, suggests an alternate future historical record. It covers Obama’s presidency episode by episode, giving each one the same degree of importance it had at the time. His account of the stimulus, for instance, treats the episode primarily as an attempt to win the favor of Republicans in Congress. He concludes it failed, because, “far from drawing up a truly bipartisan bill, Obama would claim the veneer of bipartisanship with only Snowe, Collins and Specter for cover.” Todd’s own description showed that bringing on more Republicans would have required making the stimulus smaller (and less effective), but measuring the law as an attempt to save the economy, rather than to bring the two parties together, holds almost no interest for him.

Todd confines his description of Obama’s education reforms to a single sentence. (Not even the entire sentence, either -- a clause within a sentence.) He omits any mention of the administration’s climate action plan. Todd does devote several pages to BP’s offshore oil-rig explosion, which captivated journalists for weeks before the Obama administration found a way to plug the leaking oil. He briefly notes that the administration did in fact pull off a technically challenging task in sealing off the spill. “But politically,” Todd writes, “while he certainly prevented the spill from becoming a Katrina rerun for the Gulf Coast, the president somehow never looked comfortable running this successful operation.” The structure of this sentence reveals Todd’s entire analytic method: The administration’s substantive success is the dependent clause. The Stranger rates Obama somewhere between a disappointment and an outright failure, concluding, “His legacy will be a generation of political division”—an appropriate summation of how many Americans experienced Obama’s presidency as a political drama.

In an April speech at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library to praise the 36th president’s legacy, Obama turned to the theme of vindication in an explicit way. His choice of Johnson was a telling one. No American president left such a gap between the scale of his lasting accomplishments and the indignities he suffered in his own time. The Democrat who dismantled legal apartheid in the South and created Medicare and Medicaid was so loathed he did not even bother trying to run for reelection. At times in the speech, Obama linked Johnson’s travails to his own. The triumphs of history that seem clear and simple in retrospect, he noted, felt contemporaneously grueling and ugly. “From a distance, sometimes these commemorations seem inevitable, they seem easy,” Obama said. “All the pain and difficulty and struggle and doubt—all that is rubbed away.” You can sense his desperate wish to arrive at a vantage point where his accomplishments will be buffed of disappointment and take on the same heroic gloss.

One can imagine future histories that focus less on Obama’s dysfunctional relationship with Congress, and that measure accomplishment in more discerning proportion. But the lesson Johnson offers for Obama’s own eventual vindication is not quite so encouraging. LBJ’s political career was defined by his singular failure in Vietnam. The hatred this spawned blotted out his massive and more enduring achievements. The current film Selma inaccurately depicts Johnson as an opponent of the civil-rights struggle he had, in reality, thrown all his energy behind. Five decades on, Johnson still has not escaped the feelings he engendered—indeed, he still requires rehabilitation by figures like Obama.

Johnson is hardly unique in this way. American historical memory is heavily inflected with sentiment. John F. Kennedy remains an iconic figure despite his negligible record. Ronald Reagan has won a legacy as the restorer of American hope and the winner of the Cold War, as if communism fell not as a result of its own dysfunction and four decades of Western containment but because no U.S. politician ever previously thought to tell the Soviets to tear down that wall. Partisan folklore does not inevitably give way to calm appraisal. Andrew Jackson, still introduced to schoolchildren as the hero of the common man, was a white supremacist with a fanatical hatred for any government role in economic development—a kind of 19th-century Ron Paul, but with a genocidal militaristic foreign policy. Ulysses S. Grant, taught as a corrupt and overbearing warlord, was also an effective champion of racial progress as both general and president. Two centuries on, the fog of mythos enveloping these figures has yet to dissipate.

Economists and political scientists will appreciate the scale of Obama’s successes over the long run, as many of them do already. But historians are storytellers, and the moody presentism that has rendered Obama an enigmatic failure will not automatically give way to quantifiable assessment. The president’s most irrational trait may be his inordinate faith in the power of reason itself.

*This article appears in the January 12, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment