Reviewed:

Somehow, without really intending to, I absorbed many years ago a line from The Brothers Karamazov that still comes to mind, verbatim, with surprising frequency: “The impotent and infinitely small Euclidean mind of man.” It burbles up whenever a book I’m reading or a podcast I’m listening to prompts me to envision something impossible—the vast infinity stretching out before the big bang, or the notion that linear time is not real. It echoes reliably in the back of my mind when I read about AI systems that are so complex even their makers cannot fathom how they produce their results. I nearly said it aloud the other day after realizing that I’d forgotten, for the second time in a row, to turn off the burner after making a cup of tea.

The line is spoken by Ivan Karamazov, who is talking to his brother Alyosha about the impossibility of grasping the divine will, which, if God were to actually exist (Ivan is not so sure), must be far beyond human understanding. He’s also talking about the paradoxical nature of the universe itself, which pioneering mathematicians of the day proposed might operate in four dimensions, according to geometrical axioms that were totally incomprehensible. Dostoevsky, I think, was using Ivan to make a point about how modern science requires as much faith—and runs up against the same cognitive frontiers—as religion. Just as the believer will never understand why an omnipotent and merciful God allows evil, so atheist intellectuals like Ivan cannot force their brains to imagine an infinity in which two parallel lines meet. This is owing not to a dearth of knowledge but to the limits of the operating system. “All such questions,” as Ivan puts it, “are utterly inappropriate for a mind created with an idea of only three dimensions.”

The Trouble with Reality

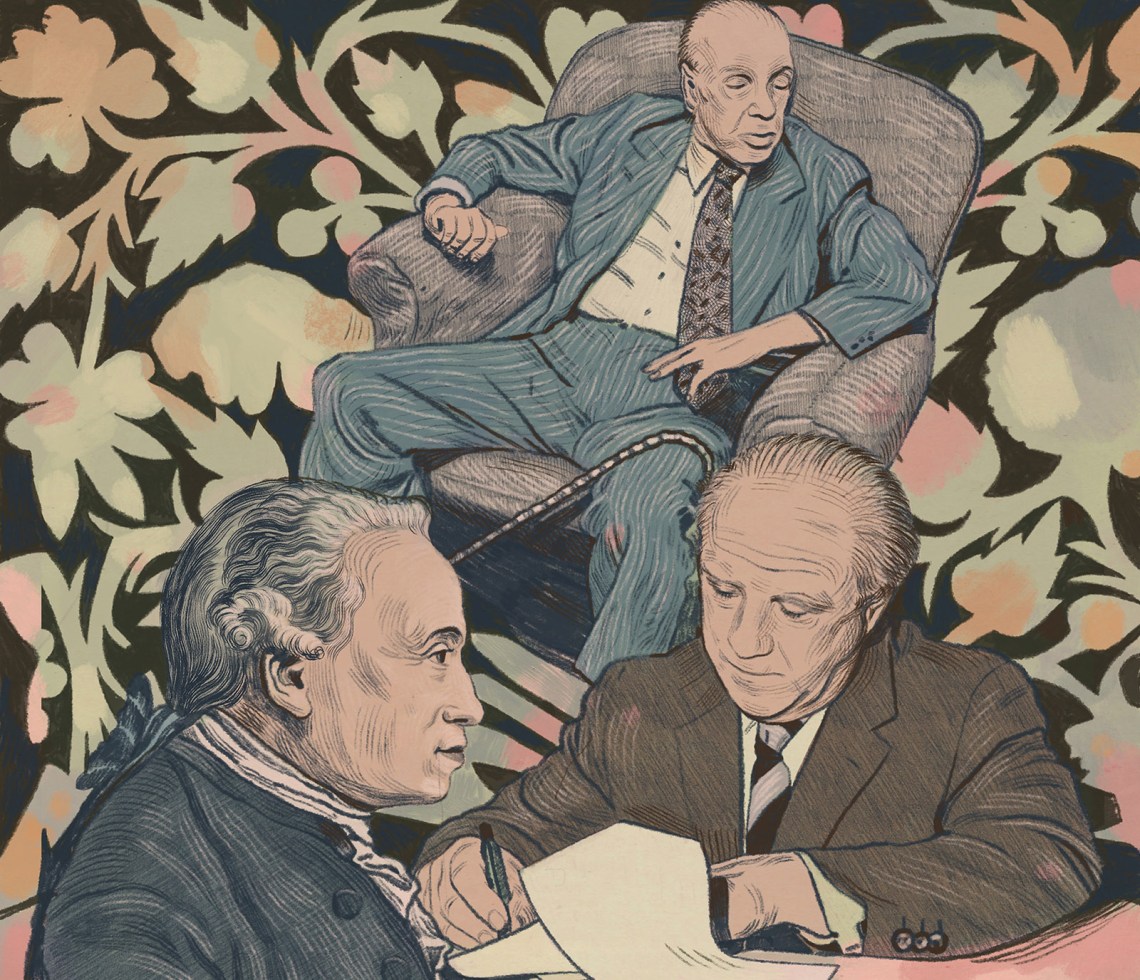

Immanuel Kant, Jorge Luis Borges, and Werner Heisenberg; illustration by Anna Higgie

Somehow, without really intending to, I absorbed many years ago a line from The Brothers Karamazov that still comes to mind, verbatim, with surprising frequency: “The impotent and infinitely small Euclidean mind of man.” It burbles up whenever a book I’m reading or a podcast I’m listening to prompts me to envision something impossible—the vast infinity stretching out before the big bang, or the notion that linear time is not real. It echoes reliably in the back of my mind when I read about AI systems that are so complex even their makers cannot fathom how they produce their results. I nearly said it aloud the other day after realizing that I’d forgotten, for the second time in a row, to turn off the burner after making a cup of tea.

The line is spoken by Ivan Karamazov, who is talking to his brother Alyosha about the impossibility of grasping the divine will, which, if God were to actually exist (Ivan is not so sure), must be far beyond human understanding. He’s also talking about the paradoxical nature of the universe itself, which pioneering mathematicians of the day proposed might operate in four dimensions, according to geometrical axioms that were totally incomprehensible. Dostoevsky, I think, was using Ivan to make a point about how modern science requires as much faith—and runs up against the same cognitive frontiers—as religion. Just as the believer will never understand why an omnipotent and merciful God allows evil, so atheist intellectuals like Ivan cannot force their brains to imagine an infinity in which two parallel lines meet. This is owing not to a dearth of knowledge but to the limits of the operating system. “All such questions,” as Ivan puts it, “are utterly inappropriate for a mind created with an idea of only three dimensions.”

The irony, of course, is that Ivan cannot stop himself from asking those inappropriate questions. By the end of the novel, he goes mad, pushing reason to its absurd outer limits. It’s a persistent human error; we cannot resist trying to understand what we are hardwired not to. If anything, the death of God has left a conspicuously empty seat in the rafters that we keep trying to inhabit—that purely transcendent, objective vantage outside the totality of things. Spinoza called it sub specie aeternitatis. Hannah Arendt named it “the Archimedean point.” Thomas Nagel termed it the “View from Nowhere.”

William Egginton, a literary scholar at Johns Hopkins, calls this tendency “metaphysical overreach.” His new book, The Rigor of Angels: Borges, Heisenberg, Kant, and the Ultimate Nature of Reality, is a joint biography of three figures who called attention, much as Dostoevsky did, to the problems and paradoxes that emerge when we try to extend our ordinary way of seeing the world beyond the human scale. These contradictions—or what Kant called antinomies—arise when we try to eject ourselves beyond space and time, imagining earthly life from an eternal perspective. (Egginton calls this illusory vantage “the god of very large things.”) They also arise when we zero in too closely on things at a minute scale. (Egginton calls this, borrowing a phrase from Arundhati Roy, “the god of very small things.”)

Whether large or small, the point of view is presumed to be objective, unmoored, and impartial: hence the false divinity. This is not a new problem, but Egginton argues that it slyly persists in many thought experiments and theories, including the multiverse hypothesis, interpretations of quantum mechanics, and debates about free will. Borges, Kant, and Heisenberg each cautioned against such confusions and, as Egginton puts it, “shared an uncommon immunity to the temptation to think they knew God’s secret plan.”

No comments:

Post a Comment