Joe Biden’s Endless Search for the Middle on Race

From the beginning of his career in public life, Joe Biden’s instinct has been to recoil from those he considers the hard-charging activists in his party, and to find ways to understand those he knows his own allies would detest.

Biden thinks that’s his special insight into politics, that he’s a bridge builder—but it’s meant building bridges to people others think don’t deserve any kind of bridge. He seems to think that approach is especially useful over issues of race. There are archives full of comments, in newspaper accounts and videos, of Biden trying to explain his thinking on the matter. But given how much the conversation over race has changed in the past 50 years, that’s left him with a lot of remarks and relationships that can look out of sync in 2019, even as the 76-year-old former vice president says he’s still the same guy he always was. The comments reinforce a vulnerability—one his opponents have already jumped on.

The thread is there in his first big interview before his inaugural Senate run: “I have some friends on the far left, and they can justify to me the murder of a white deaf mute for a nickel by five colored guys. They say the black men had been oppressed and so on. But they can’t justify some Alabama farmers tar and feathering an old colored woman,” Biden said in November 1970, just as he was coming onto the political scene. He had just won his first election to the New Castle County Council, and he was featured in a major profile in the Wilmington, Delaware, News Journal with a splashy headline: “Joe Biden: Hope for Democratic Party in ’72?”

“I suspect the ACLU would leap to defend the five black guys,” Biden continued in the interview. “But no one would go down to help the ‘rednecks.’ They are both products of an environment. The truth is somewhere between the two poles. And rednecks are usually people with very real concerns, people who lack the education and skills to express themselves quietly and articulately.”

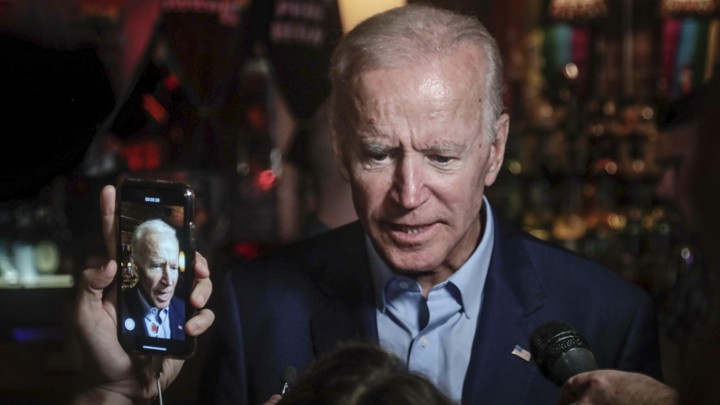

That was the thinking Biden seemed to be reflecting on Tuesday night at a New York City fundraiser when he recalled working with two of the most famous segregationists in the Senate. Pushing back on Democrats who’ve called for a take-no-prisoners approach to dealing with congressional Republicans, he noted that Senator James Eastland of Mississippi “never called me ‘boy’—he always called me ‘son.’” Henry Talmadge of Georgia, meanwhile, was “one of the meanest guys I ever knew,” Biden said.

“Well, guess what? At least there was some civility,” Biden added. “We got things done.”

Biden has reacted with frustration to the blowup, with most of his most prominent 2020 rivals, and a number of other prominent liberals, aghast that he could wistfully invoke names like Eastland, often known as “the voice of the white South.” That frustration has created another layer of issues: After Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey called on Biden to apologize, Biden’s deputy campaign manager, Kate Bedingfield, struggled to explain, in an appearance on CNN Friday morning, why Biden had said Booker should apologize to him instead.

Biden has reacted with frustration to the blowup, with most of his most prominent 2020 rivals, and a number of other prominent liberals, aghast that he could wistfully invoke names like Eastland, often known as “the voice of the white South.” That frustration has created another layer of issues: After Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey called on Biden to apologize, Biden’s deputy campaign manager, Kate Bedingfield, struggled to explain, in an appearance on CNN Friday morning, why Biden had said Booker should apologize to him instead.

Biden says he has nothing to apologize for and that his record speaks for itself. “I’ve been involved with civil rights my whole career—period, period, period,” Biden said on Wednesday evening, citing specifically his work extending the Voting Rights Act. That’s the defense from his campaign: His adviser Symone Sanders tweeted Wednesday afternoon that Biden “literally ran for office against an incumbent at 29 because of the civil rights movement.” Yesterday, she told me that Biden had run “because he disagreed with the segregationist senators in office at the time.” Biden didn’t seem to talk much about that particular motivation during his first Senate campaign, though a story the segregationist Senator John Stennis of Mississippi told late in life, which was recounted in a 2007 Delta Democrat-Times article, provides some backup. When Stennis asked Biden in 1973, according to the article, “‘Why did you get into politics?’ Biden looked him in the eye and said, ‘Civil rights.’”

Biden has struggled to explain himself on race and civil rights for decades, and for decades, liberals have been suspicious of those explanations—though perhaps never more so than now, with Biden campaigning on restoring the good ol’ days and many in his party arguing that those days weren’t as good as he remembers. (His campaign press secretary declined to comment on the candidate’s previous statements in his career.)

Once he arrived in the Senate in the early 1970s, Biden prioritized the fight against busing to integrate public schools, pushing for an amendment that he said would expose liberal doubts about the practice. In a Philadelphia Inquirerarticle in 1975, Biden said, “I think I’ve made it possible for liberals to come out of the closet.” When he was running for reelection in 1978, the Wilmington Morning News wrote that “the only substantive legislation bearing Biden’s name to reach the nation’s law books is the Biden-Eagleton Amendment, which has shut down efforts by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to achieve busing for school desegregation.”

Biden had placed himself firmly on one side of one of the fiercest fights about race of the 1970s (a position a spokesperson said in March he still stands by). He spoke often about how he did not believe in the theory behind busing—that there was a greater good achieved by that method of forcing integration. As he put it in a November 1976 speech, according to the News Journal, “black kids don’t want to come to your school any more than you want to go to their school.”

Biden argued that he was just pursuing common-sense solutions when he pushed back on liberals’ support for busing, along with racial quotas in schools. But he was making unsavory allies along the way. When he became chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1980—a position for which Eastland had backed him—Biden said he wouldn’t fight over busing with Strom Thurmond, the South Carolina senator and famous segregationist who’d become a friend. But, he told the News Journal in 1980, “if Strom Thurmond is serious about eliminating the Voting Rights Act, I’m going to fight it. I’ll be visible in that fight.”

News accounts at the time suggest that Biden was not integrally involved in crafting the reauthorization of the VRA. One referred to him as playing “second fiddle” in the process. But they do credit him with arranging a meeting between civil-rights activists and then–Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole, in a move that helped get the bill passed and onto then-President Ronald Reagan’s desk.

Biden believes actions like these demonstrate his true character. He supported making Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a national holiday, calling the leader “the social conscience of this nation.” And he opposed Jeff Sessions’s 1986 nomination to a federal judgeship over his comments calling groups like the NAACP un-American.

“People have tremendous difficulty accepting how could I be for civil rights and against busing,” Biden told the Morning News in August 1986. He said he was just being practical, seeking compromise. “I’ve always viewed my role, what I’ve done best in the Senate, as one of the guys who kept the pendulum in the middle,” Biden said.

That February, Biden had given a similar nonideological pitch in Birmingham, Alabama, as he prepared for his 1988 presidential run. Introduced by then-Senator Howell Heflin of Alabama, who said Biden had “enthralled” attendees at Stennis’s birthday party three years earlier because he “understands the South,” Biden gave a version of his stump speech, though he tinkered with the section focused on race. He told the crowd that he felt like the time for apologies was past. “A black man has a better chance in Birmingham than in Philadelphia or New York,” he said, according to a report in the Morning News from that evening.

In other settings back then, Biden reflected angrily on the Jim Crow South, even as he inflated his own history with the civil-rights movement. He told the New Jersey state Democratic convention in 1983, “When I was 17, I participated in sit-ins to desegregate restaurants and movie houses.

“My stomach turned upon hearing the voices of [Orval] Faubus and [George] Wallace,” Biden continued, referring to the segregationist governors of Arkansas and Alabama, respectively. “My soul raged on seeing Bull Connor and his dogs.”

By September 1987, his campaign press secretary clarified to The New York Times that Biden “did participate in action to desegregate one restaurant and one movie theater.” Or as Biden once explained at a 1987 news conference, he’d been concerned about civil rights as a teenager, but he “was not out marching.” He’d “worked at an all-black swimming pool on the east side of Wilmington,” Biden said, and “was a suburbanite kid who got a dose of what was happening to black Americans.”

The middle is where and how Biden always thinks of himself. “I was never an activist,” Biden once said. “I didn’t march on Selma. Vietnam wasn’t a big issue in my college days. I was a middle-class kid in a sports coat.” Biden graduated from the University of Delaware in 1965, before the anti-war protests peaked. He enrolled in Syracuse University for law school, graduating in 1968, but he explained at the 1987 presser, using similar language, how he remained apart from what was happening in the streets. “By the time the war movement was at its peak ... I was married, I was in law school, I wore sports coats … I’m not big on flak jackets and tie-dyed shirts. And you know, that’s not me,” he said.

Yet for all the talk about civil rights, Biden never lost his personal fondness for the segregationists he worked with in the Senate. A decade before he delivered his now famous eulogy at Thurmond’s funeral—in which he called the old Dixiecrat “a product of his time”—Biden spoke at the senator’s 90th birthday party in Washington, D.C., in March 1993. Standing in a tuxedo, Biden compared Thurmond to the Confederate general Robert E. Lee: “an opponent without hate, a friend without treachery, a statesman without pretense, a soldier without cruelty and a neighbor without hypocrisy.” He talked, too, about Stonewall Jackson. Quoting the Confederate soldier James Power Smith writing about the general he served under, Biden said, “He was an avalanche from an unexpected quarter, a thunderbolt from the sky, and yet he was in character and will, more like a stone wall than any man that I have ever met.

“That seems to me to sum up Strom Thurmond: He is like a thunderbolt from the sky,” Biden continued. “He is a man who lives by his principles and a man who has gotten all of us to understand what they are.”

Biden used to like that line about a “thunderbolt from the sky”; he’d used a variation of it at a birthday party for Stennis in 1985. Stennis had also once compared Biden to Jackson. In his 2007 book, Promises to Keep, Biden recalled how nervous he was giving his first speech on the Senate floor, and how Stennis had sent him a typewritten note afterward: “I watched you today as you took the floor. You stood tall—like a stone wall. Like Stonewall Jackson.”

Over the years, Biden has changed how he’s spoken about his own place in the fight for civil rights. He talks often now about standing on the train platform in Wilmington on January 20, 2009, waiting to meet Obama so they could ride to their inauguration together, and thinking about the riots that he had seen in that same neighborhood during the 1960s. He was involved in another reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act in 1982, and in 2012 he famously jumped ahead of Obama on endorsing gay marriage, forcing the president’s hand on the issue.

In March 2016, watching Donald Trump march forward through the Republican primaries, Biden started speaking out against the institutional racism he said was evident in laws that had restricted voting rights and access to credit. “We all kind of knew it, but we didn’t quite talk about it,” he said then at a Naval Observatory reception for Black History Month. Last year, he was even given the Freedom Award by the National Civil Rights Museum.

So on Wednesday night, at his second fundraiser of the evening, Biden tried to offer more context to his controversial comments earlier in the week. “We had to put up with the likes of Jim Eastland and Hermy Talmadge and all those segregationists and all of that,” he said. “We, in fact, detested what they stood for in terms of segregation and all the rest.”

The Stonewall Biden wants people to associate him with these days is the one he visited earlier this week in New York, a few hours before the comments that brought on the trouble: the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, site of the 1969 riots that transformed the gay-rights movement.

“The ultimate civil-rights argument today is, how can you be constitutionally able to marry and be able to be fired in three dozen states when you walk in?” Biden said. “Imagine the courage it took 50 years ago to stand up and say ‘I’m gay,’ ‘I’m trans,’ ‘I’m whatever,’ ‘I’m a lesbian’ … The public’s way ahead of the politicians on this. They were way ahead on marriage, and they are way ahead on the basic rights that every American should have.”

That’s where Biden says he is now. But that’s more than he ever seemed to say about civil rights for years after he started out.

No comments:

Post a Comment