I started this book with a goal of wanting to like Booker T. Washington. After all, he is an icon of American history who accomplished the founding of Tuskegee University, a big part of the history of my native Alabama as well as the whole country. After reading the book, I find reasons to like him, but I also find reasons to question him.

Based on this famous book, BTW had a rosy picture of American race relations as he was writing at the turn of the 20th Century. What would he say about what the riots and protests going on in our country at this very minute? No way to know since he isn't here, but I cannot help but believe that he would be surprised that with his optimistic view of things that the country would have all of this behind us by now. Today's racial atmosphere in this country can make Washington look pollyannish.

I remind myself that this reminiscence was written at a particular point in his life. He lived for 15 more years. As far as I know, this is the only biographical book he would ever write. This is his view at the turn of the century before he lived for 15 more years. Some of his views could have changed before he died.

Born into slavery but young enough to have lived until 1915, he lived through a country that went thru a lot of changes.

"Of my ancestry I know almost nothing." P. 1 This is one of the harshest thing about slavery. Most slaves were probably in the same situation.

He speaks of the sometimes close attachment of slaves and white owners yet all slaves wanted freedom. Since I wasn't there, this is a hard thing to wrap my head around. P. 5

No bitterness against Southern whites on account of the enslavement of his race? He had a big heart is all I can say. P. 5

Faith in the future to overcome slavery. I think he might be disappointed today. P. 6

A theme in the book is his strong belief in eduction. Inspiring how he shows up at Hampton with 50 cents in his pocket.

His entrance exam was a sweeping job! You can't beat a story like this. P. 17

Throughout the book he talks about General Samuel C. Armstrong, a Yankee general I take it, because "fought the Southern white man." Gen. Armstrong, the finest man Booker ever knew, is the man who gets him the job at Tuskegee. P. 18

Mother's death. P. 23

Goes very lightly over the KKK. P. 26

Proud that he wasn't "called" to preach. P. 28

Seems to equate Southerners reaching to the federal government for help during Reconstruction like a child reaching for his mother. Not a good analogy, Booker. P. 28

Preferred a Reconstruction approach of education and property. He may have been right. P. 28

Reluctant to punish Southern white men. Wrong on this. P. 28

Points out unworthy blacks taking positions of responsibility during Reconstruction. This is not good politics today. P. 29

Industrial training over Latin and Greek. P. 30

Got along well with Indians. P. 33

Meeting Frederick Douglass. P. 33

Big fan of "night schools" to give working people a chance at an education. P. 35

General Armstrong (a Bluecoat who killed Southerners) led Booker to Tuskegee, Alabama, to start a "normal" school. A normal college was to train teachers. Tuskegee seemed like a good place to start a school. Five miles from the railroad. In the midst of the great bulk of Negro people. The white people of Tuskegee seemed more educated and sophisticated than most Alabama white people. The colored people were ignorant, but had not the typical vices of lower classes. Relations between the races were pleasant. Booker also put the best light on everything. P. 37

He reached Tuskegee in June of 1881. The story of the building of Tuskegee Institute by students with BTW scouring the country for funds is the highlight of this book. P. 38

From the beginning of Tuskegee BTW kept claiming that race relations were getting better in the South. P. 38

He certainly put the Tuskegee students to work! P. 39

He makes fun of the caricature of what white people thought an educated black person would look like. P. 40

He always stressed practical, vocation, industrial education. Better master the multiplication tables before banking and discount. P. 42

Live by your wits or live by your hands? BTW seemed to want his students to live by their hands if they found it meaningful. I agree. P. 43

Students erected the buildings at Tuskegee. This is quite amazing. P. 50

Big emphasis on brick making at Tuskegee. Making something white people desired made for better racial relations. P. 51

"The individual who can do something that the world wants will, in the end, make his way regardless of race." Maybe this is his philosophy in a nutshell. Is BTW right? P. 52

He never heard Gen. Armstrong say a single bitter word against the people of the South. P. 55

He says he rid himself of any hatred of Southern white people for the wrongs they inflicted on blacks. He pitied anyone holding race hatred. It's hard to believe this. Either BTW was a great man or a naive fool. P. 56

He says he never received a single personal insult from a white person in the South. Hard to believe. P. 57

The students made their own furniture. Tuition was $50 a year. The first building was Porter Hall. I wonder what happened to it. P 60

He was certainly successful in cultivating rich people for donations to Tuskegee. He deserves all the credit in the world for this.

It is as if he felt that blacks had to earn their way to full citizenship. If this is correct, he is wrong. P. 69

The most famous episode in Washington's life was his address in 1895 at the Atlanta Exposition. Call it his Atlanta Exposition Address. In this book he quotes the entire speech. His most famous words were: "In all things that purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in things essential to mutual progress." Historians have said here he was endorsing segregation, which is not acceptable. This is the source of most of the negativity directly towards Washington over the years. Does he deserve this criticism??? P. 75

In this address he goes on to say:

"The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must the result of severe and constant struggle rather than artificial forcing. No race that anything to contribute to markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized. It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but is vastly more important that we be prepared for these privileges. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera house." P. 76 What do we make of this???

Southern whites will give Blacks their rights as soon as they earn them. This seems to be what he is saying. It will not be through artificial forcing. P. 79

The time will come when the South will encourage all of its citizens to vote. Ha! Yet at this point he endorses "protections" in the way of property or education. What about poll taxes? P. 80

He travels the country. He and the Misses have a grand trip touring Europe. BTW was known worldwide.

He liked pigs and chickens. Yuk! P. 90

He was impressed with the Holstein cattle. Somehow I find this funny. P. 94

Blacks have to earn their way, make themselves indispensable. I hate to say it, but it seems in places that he too readily accepts white privilege, but then I have to remember the time and place where he was. I cannot put myself in his place in his time. P. 95

Reading a life of Frederick Douglass. P 97

He closes his account in the city of Richmond, the ending capital of the Confederacy. Perhaps this is appropriate. P. 109

Finis

Sunday, May 31, 2020

Comments on Freddy's Post

Biography

- Washington was born in 1856 as a slave in Virginia. I CANNOT IMAGINE BEING A SLAVE. THIS IS SO FAR FROM MY CONTEMPORARY ORIENTATION.

- His mother was a slave, and his father was a white man from a different plantation. HIS FATHER APPARENTLY HAD NO INTEREST IN HIM. THIS WOULD BE HARD FOR ME TO LIVE WITH.

- His mother was the plantation cook; their cabin also served as the kitchen.

- He didn’t sleep in a bed until after the Civil War. Growing up, he slept on rags on the ground with his brother and sister. TOUGH TO IMAGINE.

- He didn’t know his father. He doesn’t blame his father for not taking responsibility for him; he says that was how the system of slavery was. AWFUL BIG OF HIM! I WOULD HAVE HELD IT AGAINST HIM!

- Washington wanted to learn to read from a young age, an ambition supported by his mother. However, as a kid he was forced to work. Eventually, he was able to attend school while still working. Most of his schooling as a youth was at night. HE OBVIOUSLY HAD A LIFELONG WORK EITHIC THAT HE TRIED TO INSTILL IN TUSKEEGEE STUDENTS---SOMETHING TO CERTAINLY to LAUD BTW FOR.

- During his life, he read a lot, although “Fiction I care little for.” He read mainly newspapers and biographies. “I think I do not go too far when I say that I have read nearly every book and magazine article that has been written about Abraham Lincoln.” A READER BUT NOT NECESSARILY SOMEONE WE COULD SAY WAS WELL-READ?

Slavery

- Washington says that it was clear to everyone that the Civil War was about slavery. “When war was begun between the North and the South, every slave on our plantation felt and knew that, though other issues were discussed, the primal one was that of slavery.” NO DOUBT

- Although black slaves were uneducated, they were still be aware of the great societal issues facing the country. Slaves on the plantations would discuss slavery, Lincoln, and other questions. They were aware of current events through word of mouth. For example, a black person would overhear whites discussing something, and then he'd share that news with other slaves. The information would pass from there. THIS IS ONE THE MOST FASCINATING PARTS OF HIS STORY. AMAZING HOW THESE PEOPLE IN SLAVERY KNEW WHAT WAS GOING ON.

- Washington asserts that “...the black man got nearly as much out of slavery as the white man did.” Blacks, for example, learned handicrafts, since they did the work on the plantation. Whites did not do labor. Once slavery ended, whites were left unprepared to fend for themselves. ONE WISHES THAT HE WOULD HAVE LASHED OUT AGAINST SLAVERY RATHER THAN PUT ANY KIND OF POSITIVE LIGHT ON IT. I DON'T UNDERSTAND THIS. WHITES DID NOT DO LABOR? I WOULD HOLD THIS AGAINST THEM. BTW SEEMS TO OUT OF HIS WAY NOT TO CRITICIZE WHITE PEOPLE.

- When emancipation came, whites were not sad for their lost property. Rather, they were sad that the slaves, who had been part of their lives for so long, were now gone. Blacks, in contrast, were initially ecstatic to have freedom. However, they now had to care and provide for themselves for the first time. This great responsibility was difficult and gloomy. NO DOUBT. THE INITIAL YEARS AFTER EMANCIPATION WERE SCARY AND DIFFICULT FOR EVERYONE MUCH MORE SO FOR BLACKS THAN WHITES. BTW SEEMS TOO NICE AT TIMES.

- Slaves were usually called by their first name only. If they had a last name, it was the same as their owner. Most slaves took new last names when they became free. For Washington, when he started school, his classmates had last names. However, the only name he had ever known was “Booker.” So, to be like his classmates, he made up a last name and chose "Washington." He later learned that his mother had given him the last name of "Taliaferro," which he wasn't aware of. Hence, he became “Booker T. Washington.” TOTALLY FASCINATING. WAS HIS WHITE FATHER NAMED TALIAFERRO? HE WAS ABLE TO SELECT HIS OWN LAST NAME. HOW MANY PEOPLE GET TO DO THAT? BOOKER WASHINGTON CERTAINLY SOUNDS BETTER THAN BOOKER TALIAFERRO.

Tuskegee and approach to education

- Washington attended Hampton Institute, which had a profound effect of his life. There he learned to work hard, be in service to others, appreciate the Bible, and “the dignity of labour.” He worked as a janitor to pay his education expenses at Hampton. GOOD PART OF HIS ACCOUNT. I DID NOT KNOW ANYTHING ABOUT HAMPTON ALTHOUGH I HAD HEARD OF IT BEFORE READING THIS.

- He started the school in Tuskegee in June 1881. There was little money, no land, and no buildings when he arrived at Tuskegee. THE MOST IMPRESSIVE THING ABOUT BTW IS HOW HE BUILD TUSKEGEE. AN AMAZING ACCOMPLISHMENT.

- Tuskegee officially opened on July 4, 1881. Whites in the area feared the education of blacks. They thought that it would have an economic impact, that it would be harder to secure blacks for domestic and farming help if blacks were educated. NO DOUBT.

- All students at Tuskegee did manual labor. Washington felt that learning a skill made someone indispensable to society. To him, knowing a skill would lead to greater acceptance of blacks, because they are contributing a skill to the betterment of the community. THIS IS GOOD BUT MIGHT HAVE FIT A STEREOTYPE THAT THIS IS ALL BLACK PEOPLE WERE GOOD FOR.

- Washington saw education as a means of learning how to live and how to work. He asserted that as blacks became economically independent, they would garner more respect from whites. HE HAD GREAT FAITH IN EDUCATION. THAT FAITH MIGHT BE ON SHAKY GROUND THESE DAYS.

- He believed that blacks who were industrious had more self-reliance and character. I AGREE TOTALLY FOR ALL PEOPLE.

- Washington believed that blacks should not antagonize whites but instead develop friendly relationships with them. He also believed that blacks need to work their way up from the bottom, not start at the top of society. HE SEEMED TO THINK THAT BLACKS HAD TO TOTALLY EARN THEIR PLACE RATHER THAN HAVE THE SAME NATURAL RIGHTS AS WHITE PEOPLE. HE SEEMED TO THINK THAT BLACKS HAD TO EARN THE RESPECT OF WHITE PEOPLE RATHER THAN START OUT WITH THE SAME RESPECT THAT WHITE PRIVILEGE AFFORDED ALL WHITES TO START WITH.

- He believed in self-improvement as a means for blacks to better their lives. He also accepted segregation. This approach to racial issues conflicted with other leaders at the time, like W.E.B. DuBois. THE CRITICAL HISTORICAL QUESTION ABOUT BTW: DID HE ACCEPT SEGREGATION? IF SO, THIS WILL FOREVER STAIN HIS REPUTATION.

- The education of blacks was more difficult because of different expectations of the races. When white people do something, they are expected to succeed. Whereas when black people do something, it is surprising if they don’t fail. STILL RELEVANT TODAY.

Conclusions

- His rise from slave to founder of Tuskegee, respected and admired around the world, is remarkable. YES THE MOST LAUDABLE THING ABOUT BTW.

- His story shows the power of education.

- I think the book is very self-congratulatory. He is not shy about sharing his successes and accolades. I DON'T HAVE ANY PROBLEM WITH THIS.

- The book makes race relations sound better than they actually were. Washington describes whites as accepting of him and not resistant to his mission to help black people. I have difficulty believing that whites were so indifferent. BIG POINT HERE. I AGREE. WAS HE NAIVE? DID HE HAVE TO OPERATE THIS WAY TO BUILD SUPPORT FOR TUSKEGEE? COULD BE THAT HE RECEIVED HIS WHITE SUPPORT BECAUSE PROMINENT WHITES DID NOT FEAR HIM. THAT THEY FELT HE ACCEPTED SECOND CLASS STATUS FOR BLACKS.

Friday, May 29, 2020

John M. Barry - The Great Influenza - Notes

Between the years 1918 and1920, influenza raged around the globe in the worst pandemic in recorded history, killing at least fifty million people, more than half a million of them Americans. Yet despite the devastation, this catastrophic event seems but a forgotten moment in our nation's past.

The author shows that though the pandemic caused massive disruption in the most basic patterns of American life, influenza did not create long-term social or cultural change, serving instead to reinforce the status quo and the differences and disparities that defined American life. The pandemic would arrive quickly and dissipate quickly ultimate barely affecting the country as a whole except for the people and their families that were affected.

As the crisis waned, the pandemic slipped from the nation's public memory. The helplessness and despair Americans had suffered during the pandemic was a story poorly suited to a nation focused on optimism and progress. For countless survivors, though, the trauma never ended, shadowing the remainder of their lives with tragic memories.

It can be difficult to figure out where a pandemic begins. This author believes, amazingly, that this great pandemic began in a small town in Kansas in the spring of 1918. It spread quickly from there because the US was building up forces to send to Europe to embellish allied forces in what came to be called World War I. There was what's called a cantonment of US soldiers in this small Kansas town, and the soldiers carried the infection with them as they left Kansas. The war and the resulting mass movement of people worldwide mainly soldiers spread the virus quickly and in deadly fashion.

It can hard and inconclusive to determine the origin of a pandemic. Quick insinuations that the current pandemic originated in a lab in China is a case in point. Anyone can make such claims. All that matters ultimately is evidence that may never be conclusive.

"No one will ever know with absolute certainty whether the 1918-19 influenza virus did originate in Haskell County, Kansas." P. 98 There will always be other theories of origination.

One of the exciting side stories in this book is that the author gives the reader a sense of how modern, scientific medicine was born in this country from the late 19th Century into the early 20th Century. The germ theory of medicine was gradually accepted as it is today. It is amazing how long it took for the correct understanding to be accepted.

One of the other side stories is President Woodrow Wilson in Paris in 1919. The flu virus was still very much active. Wilson was there to negotiate the treaty that ended the war. He had his principles to establish what he called making democracy safe. He would have relatively lenient to Germany. This author says he caught the virus while negotiations were underway. It is a fact that he was sick for several days. The assertion is that his sickness led him to give way to French desire for more stringent penalties against Germany which included Germany assuming all blame for the conflict. That leads to saying that the harsher penalties provided fodder for Hitler to gain power in Germany and hence WW II. If this is true, then it is surely the longest acting most important consequence of the great flu outbreak of 1918-19.

I am struck by how the author highlights the city of Philadelphia as a city hard city by the influenza. The city was devastated. One reason was poor municipal leadership. On the other hand, San Francisco did pretty well due largely to good leadership at the top.

One difference between THEN and NOW is that we are told today that COVID-19 strikes the most vulnerable first, those elderly and/or those with certain preexisting conditions. The 1918 pandemic was different.

The book reminds the reader that throughout history more soldiers died from disease than battle wounds. P. 135

Like today the 1918-19 pathogen was airborne. Breathing it in would cause the disease. P. 256

Pandemics come in waves. The first wave came in the spring of 1918. The second wave, much more dangerous, came in the fall. October, not April, was the cruelest month. P. 313

"There was real terror afoot in 1918, real terror. The randomness of death brought that terror home. And so did the fact that the healthiest and strongest seemed the most vulnerable." P. 460

The author's biggest conclusion:

"For if there is a single dominant lesson from 1918, it's that governments need to tell the truth in a crisis. Risk communication implies managing the truth. You don't manage the truth. You tell the truth." P. 460

"So the final lesson of 1918, a simple one yet one most difficult to execute, is that those who occupy positions of authority must lessen the panic that can alienate all within a society. Society cannot function is it is every man for himself. By definition, civilization cannot survive that." P. 461

The author shows that though the pandemic caused massive disruption in the most basic patterns of American life, influenza did not create long-term social or cultural change, serving instead to reinforce the status quo and the differences and disparities that defined American life. The pandemic would arrive quickly and dissipate quickly ultimate barely affecting the country as a whole except for the people and their families that were affected.

As the crisis waned, the pandemic slipped from the nation's public memory. The helplessness and despair Americans had suffered during the pandemic was a story poorly suited to a nation focused on optimism and progress. For countless survivors, though, the trauma never ended, shadowing the remainder of their lives with tragic memories.

It can be difficult to figure out where a pandemic begins. This author believes, amazingly, that this great pandemic began in a small town in Kansas in the spring of 1918. It spread quickly from there because the US was building up forces to send to Europe to embellish allied forces in what came to be called World War I. There was what's called a cantonment of US soldiers in this small Kansas town, and the soldiers carried the infection with them as they left Kansas. The war and the resulting mass movement of people worldwide mainly soldiers spread the virus quickly and in deadly fashion.

It can hard and inconclusive to determine the origin of a pandemic. Quick insinuations that the current pandemic originated in a lab in China is a case in point. Anyone can make such claims. All that matters ultimately is evidence that may never be conclusive.

"No one will ever know with absolute certainty whether the 1918-19 influenza virus did originate in Haskell County, Kansas." P. 98 There will always be other theories of origination.

One of the exciting side stories in this book is that the author gives the reader a sense of how modern, scientific medicine was born in this country from the late 19th Century into the early 20th Century. The germ theory of medicine was gradually accepted as it is today. It is amazing how long it took for the correct understanding to be accepted.

One of the other side stories is President Woodrow Wilson in Paris in 1919. The flu virus was still very much active. Wilson was there to negotiate the treaty that ended the war. He had his principles to establish what he called making democracy safe. He would have relatively lenient to Germany. This author says he caught the virus while negotiations were underway. It is a fact that he was sick for several days. The assertion is that his sickness led him to give way to French desire for more stringent penalties against Germany which included Germany assuming all blame for the conflict. That leads to saying that the harsher penalties provided fodder for Hitler to gain power in Germany and hence WW II. If this is true, then it is surely the longest acting most important consequence of the great flu outbreak of 1918-19.

I am struck by how the author highlights the city of Philadelphia as a city hard city by the influenza. The city was devastated. One reason was poor municipal leadership. On the other hand, San Francisco did pretty well due largely to good leadership at the top.

One difference between THEN and NOW is that we are told today that COVID-19 strikes the most vulnerable first, those elderly and/or those with certain preexisting conditions. The 1918 pandemic was different.

The book reminds the reader that throughout history more soldiers died from disease than battle wounds. P. 135

Like today the 1918-19 pathogen was airborne. Breathing it in would cause the disease. P. 256

Pandemics come in waves. The first wave came in the spring of 1918. The second wave, much more dangerous, came in the fall. October, not April, was the cruelest month. P. 313

"There was real terror afoot in 1918, real terror. The randomness of death brought that terror home. And so did the fact that the healthiest and strongest seemed the most vulnerable." P. 460

The author's biggest conclusion:

"For if there is a single dominant lesson from 1918, it's that governments need to tell the truth in a crisis. Risk communication implies managing the truth. You don't manage the truth. You tell the truth." P. 460

"So the final lesson of 1918, a simple one yet one most difficult to execute, is that those who occupy positions of authority must lessen the panic that can alienate all within a society. Society cannot function is it is every man for himself. By definition, civilization cannot survive that." P. 461

Thursday, May 28, 2020

Reading Advice

7 Pieces of Reading Advice From History’s Greatest Minds

MAY 27, 2020

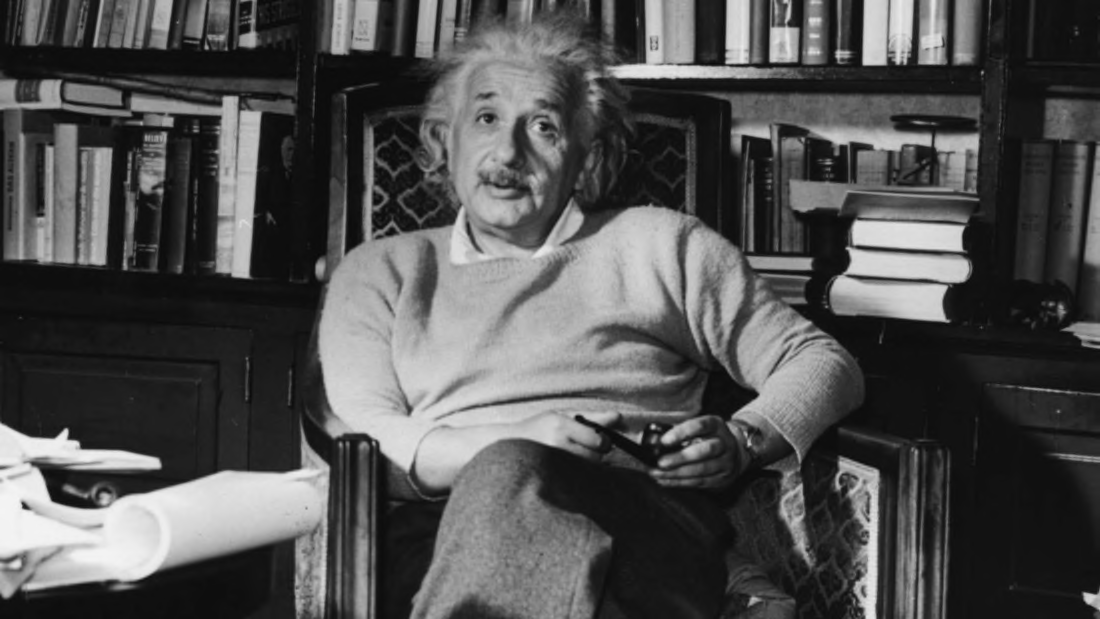

When it came to books, Albert Einstein subscribed to the "oldie but goodie" mentality. He wasn't the only one.

LUCIEN AIGNER/THREE LIONS/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

If there’s one thing that unites philosophers, writers, politicians, and scientists across time and distance, it’s the belief that reading can broaden your worldview and strengthen your intellect better than just about any other activity. When it comes to choosing what to read and how to go about it, however, opinions start to diverge. From Virginia Woolf’s affinity for wandering secondhand bookstores to Theodore Roosevelt’s rejection of a definitive “best books” list, here are seven pieces of reading advice to help you build an impressive to-be-read (TBR) pile.

1. READ BOOKS FROM ERAS PAST // ALBERT EINSTEIN

Albert Einstein poses at home in 1925 with a mix of old and new books.

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHIC AGENCY/GETTY IMAGES

Keeping up with current events and the latest buzz-worthy book from the bestseller list is no small feat, but Albert Einstein thought it was vital to leave some room for older works, too. Otherwise, you’d be “completely dependent on the prejudices and fashions of [your] times,” he wrote in a 1952 journal article [PDF].

“Somebody who reads only newspapers and at best books of contemporary authors looks to me like an extremely near-sighted person who scorns eyeglasses,” he wrote.

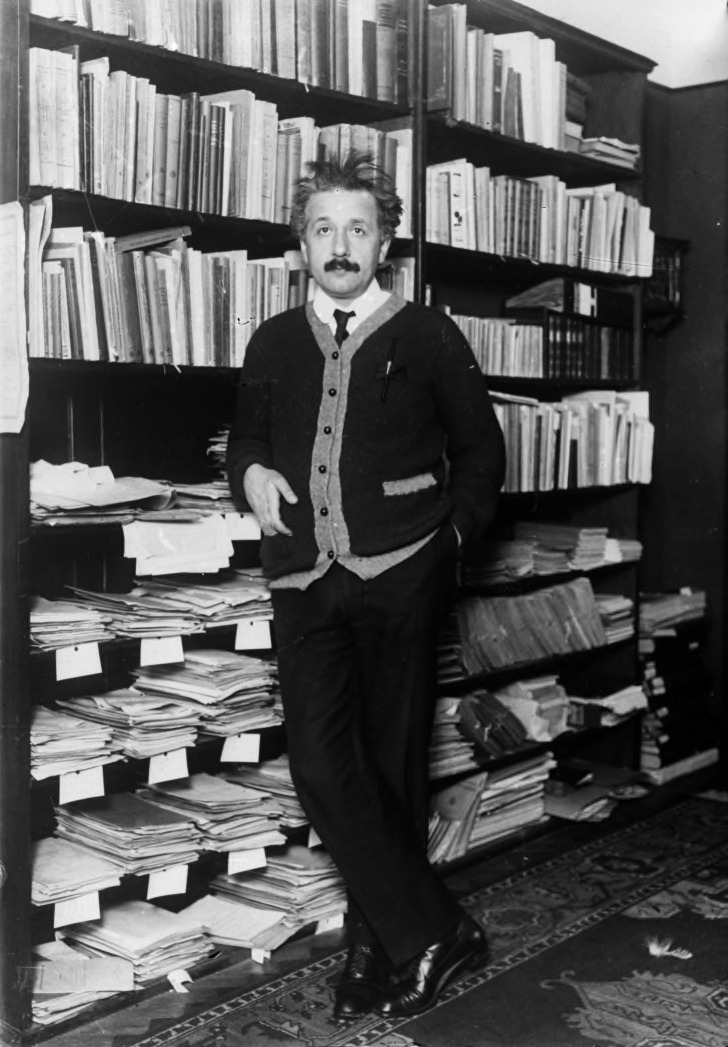

2. DON’T JUMP TOO QUICKLY FROM BOOK TO BOOK // SENECA

Seneca the Younger, ready to turn that unwavering gaze on a new book.

THE PRINT COLLECTOR VIA GETTY IMAGES

00:14

Seneca the Younger, a first-century Roman Stoic philosopher and trusted advisor of Emperor Nero, believed that reading too wide a variety in too short a time would keep the teachings from leaving a lasting impression on you. “You must linger among a limited number of master thinkers, and digest their works, if you would derive ideas which shall win firm hold in your mind,” he wrote in a letter to Roman writer Lucilius.

If you’re wishing there were a good metaphor to illustrate this concept, take your pick from these gems, courtesy of Seneca himself:

“Food does no good and is not assimilated into the body if it leaves the stomach as soon as it is eaten; nothing hinders a cure so much as frequent change of medicine; no wound will heal when one salve is tried after another; a plant which is often moved can never grow strong. There is nothing so efficacious that it can be helpful while it is being shifted about. And in reading of many books is distraction.”

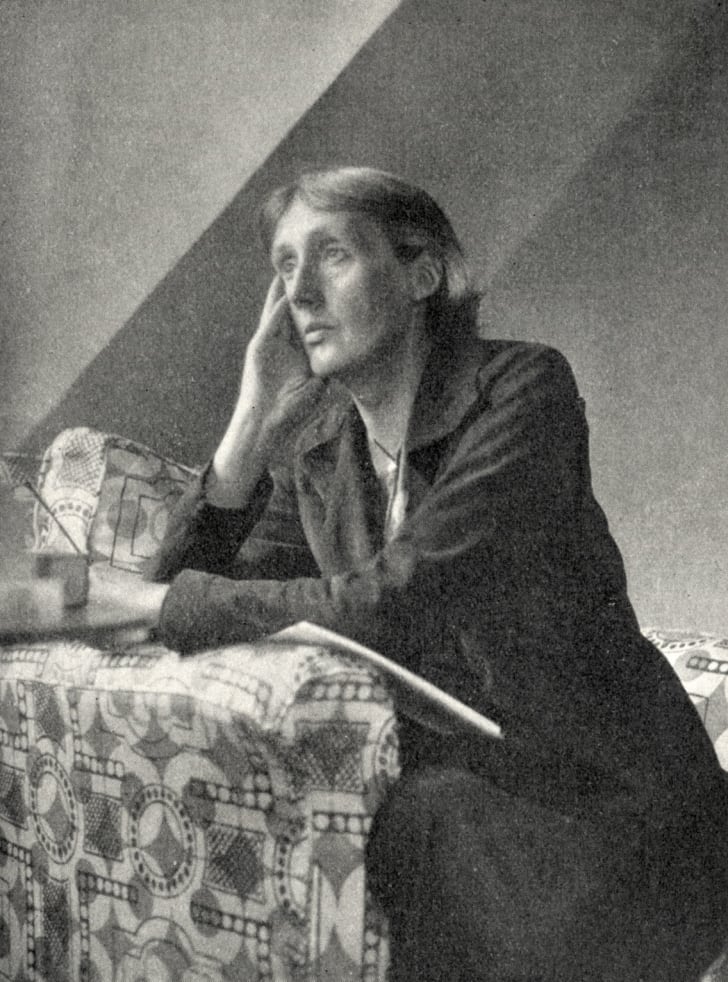

3. SHOP AT SECONDHAND BOOKSTORES // VIRGINIA WOOLF

Virginia Woolf wishing she were in a bookstore.

CULTURE CLUB/GETTY IMAGES

In her essay “Street Haunting,” Virginia Woolf described the merits of shopping in secondhand bookstores, where the works “have come together in vast flocks of variegated feather, and have a charm which the domesticated volumes of the library lack.”

According to Woolf, browsing through used books gives you the chance to stumble upon something that wouldn’t have risen to the attention of librariansand booksellers, who are often much more selective in curating their collections than secondhand bookstore owners. To give us an example, she imagined coming across the shabby, self-published account of “a man who set out on horseback over a hundred years ago to explore the woollen market in the Midlands and Wales; an unknown traveller, who stayed at inns, drank his pint, noted pretty girls and serious customs, wrote it all down stiffly, laboriously for sheer love of it.”

“In this random miscellaneous company,” she wrote, “we may rub against some complete stranger who will, with luck, turn into the best friend we have in the world.”

4. YOU CAN SKIP OUTDATED SCIENTIFIC WORKS, BUT NOT OLD LITERATURE // EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON

An 1831 portrait of Edward Bulwer-Lytton, smug at the thought of people reading his novels for centuries to come.

THE PRINT COLLECTOR/GETTY IMAGES

Though his novels were immensely popular during his lifetime, 19th-century British novelist and Parliamentarian Edward Bulwer-Lytton is now mainly known for coining the phrase It was a dark and stormy night, the opening line of his 1830 novel Paul Clifford. It’s a little ironic that Bulwer-Lytton’s books aren’t very widely read today, because he himself was a firm believer in the value of reading old literature.

“In science, read, by preference, the newest works; in literature, the oldest,” he wrote in his 1863 essay collection, Caxtoniana. “The classic literature is always modern. New books revive and redecorate old ideas; old books suggest and invigorate new ideas.”

To Bulwer-Lytton, fiction couldn't ever be obsolete, because it contained timeless themes about human nature and society that came back around in contemporary works; in other words, you can’t disprove fiction. You can, however, disprove scientific theories, so Bulwer-Lytton thought it best to stick to the latest works in that field. (That said, since scientists use previous studies to inform their work, you can still learn a ton about certain schools of thought by delving into debunked ideas—plus, it’s often really entertaining to see what people used to believe.)

5. CHECK OUT AUTHORS’ READING LISTS FOR BOOK RECOMMENDATIONS // MORTIMER J. ADLER

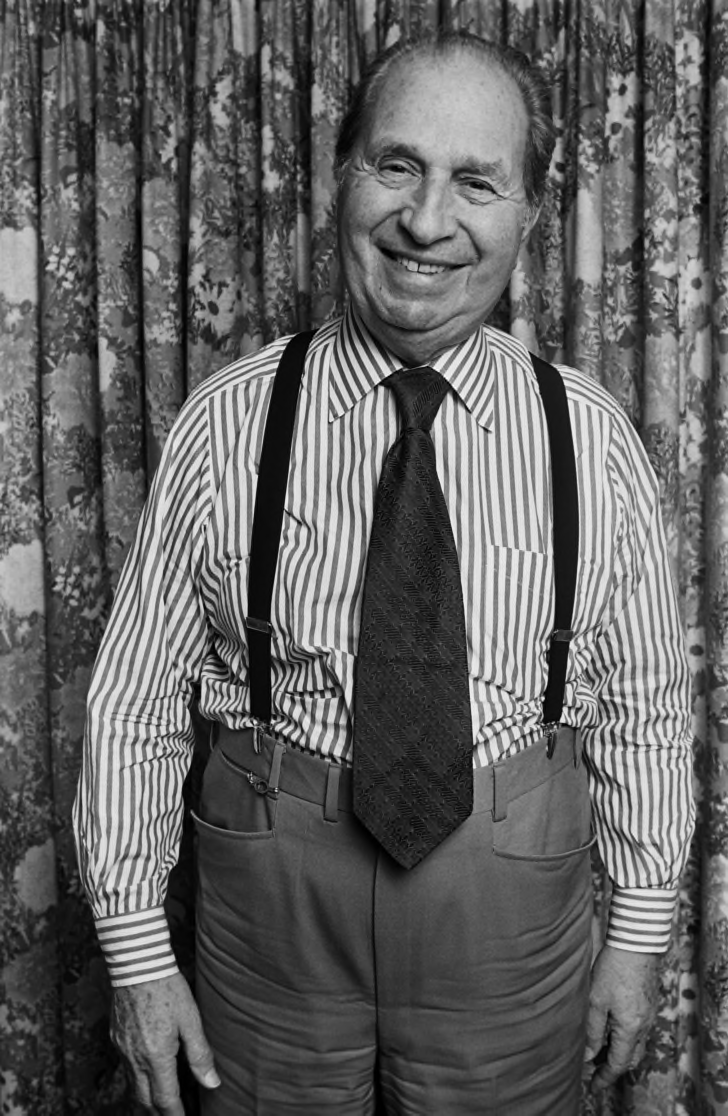

Mortimer J. Adler in 1983, happy to read the favorite works of his favorite authors.

GEORGE ROSE/GETTY IMAGES

In his 1940 guide How to Read a Book, American philosopher Mortimer J. Adler talked about the importance of choosing books that other authors consider worth reading. “The great authors were great readers,” he explained, “and one way to understand them is to read the books they read.”

Adler went on to clarify that this would probably matter most in the philosophy field, “because philosophers are great readers of each other,” and it’s easier to grasp a concept if you also know what inspired it. While you don’t necessarily have to read everything a novelist has read in order to fully understand their own work, it’s still a good way to get quality book recommendations from a trusted source. If your favorite author mentions a certain novel that really made an impression on them, there’s a pretty good chance you’d enjoy it, too.

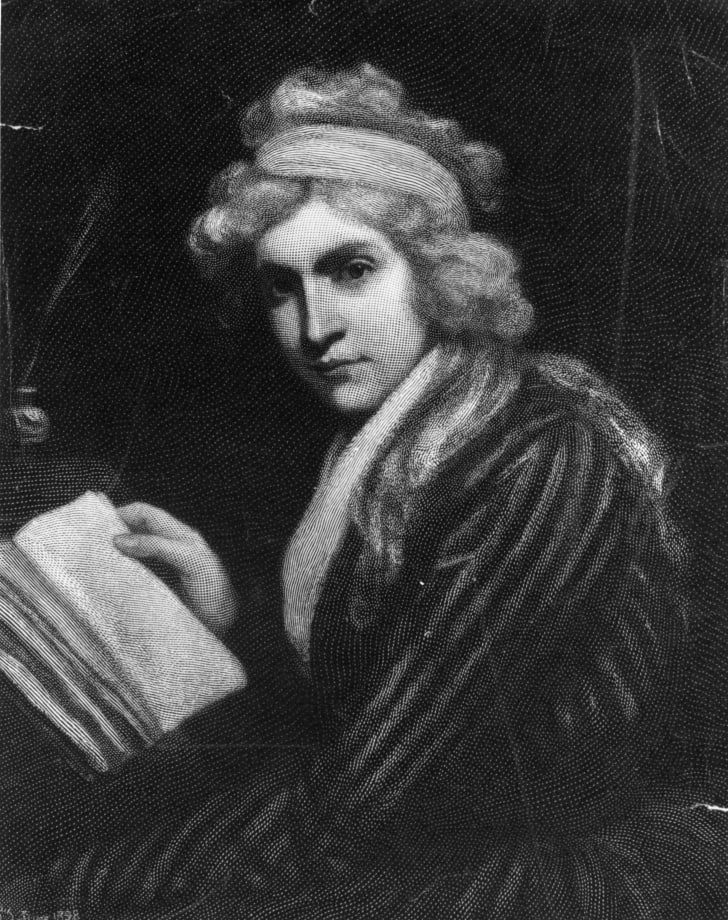

6. READING SO-CALLED GUILTY PLEASURES IS BETTER THAN READING NOTHING // MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT

Mary Wollstonecraft in 1797, apparently demonstrating that a book with blank pages is worth even less than a novel.

HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

To the 18th-century writer, philosopher, and early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, just about all novels fell into the category of “guilty pleasures” (though she didn’t call them that). In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, she disparaged the “stupid novelists, who, knowing little of human nature, work up stale tales, and describe meretricious scenes, all retailed in a sentimental jargon, which equally tend to corrupt the taste and draw the heart aside from its daily duties.”

If her judgment seems unnecessarily harsh, it’s probably because it’s taken out of its historical context. Wollstonecraft definitely wasn’t the only one who considered novels to be low-quality reading material compared to works of history and philosophy, and she was also indirectly criticizing society for preventing women from seeking more intellectual pursuits. If 21st-century women were confined to watching unrealistic, highly edited dating shows and frowned upon for trying to see 2019’s Parasite or the latest Ken Burns documentary, we might sound a little bitter, too.

Regardless, Wollstonecraft still admitted that even guilty pleasures can help expand your worldview. “Any kind of reading I think better than leaving a blank still a blank, because the mind must receive a degree of enlargement, and obtain a little strength by a slight exertion of its thinking powers,” she wrote. In other words, go forth and enjoy your beach read.

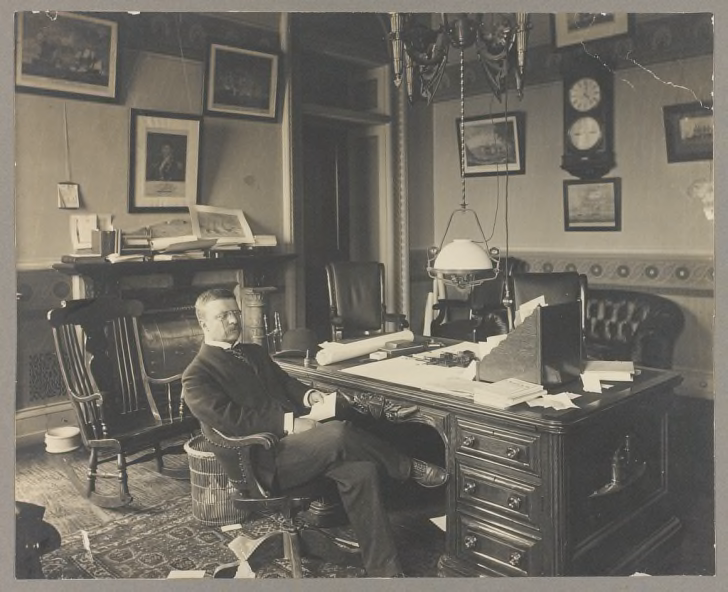

7. YOU GET TO MAKE THE FINAL DECISION ON HOW, WHAT, AND WHEN TO READ // THEODORE ROOSEVELT

Theodore Roosevelt pauses for a quick photo before getting back to his book in 1905.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PRINTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION // NO KNOWN RESTRICTIONS ON PUBLICATION

Theodore Roosevelt might have lived his own life in an exceptionally regimented fashion, but his outlook on reading was surprisingly free-spirited. Apart from being a staunch proponent of finding at least a few minutes to read every single day—and starting young—he thought that most of the details should be left up to the individual.

“The reader, the booklover, must meet his own needs without paying too much attention to what his neighbors say those needs should be,” he wrote in his autobiography, and rejected the idea that there’s a definitive “best books” list that everyone should abide by. Instead, Roosevelt recommended choosing books on subjects that interest you and letting your mood guide you to your next great read. He also wasn’t one to roll his eyes at a happy ending, explaining that “there are enough horror and grimness and sordid squalor in real life with which an active man has to grapple.”

In short, Roosevelt would probably advise you to see what Seneca, Albert Einstein, Mary Wollstonecraft, and other great minds had to say about reading, and then make your own decisions in the end.

Wednesday, May 27, 2020

Word of the Day (8)

|

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)