Saturday, November 30, 2019

Capping off Thanksgiving Weekend

By beating Alabama 48 to 45. So wonderful! We beat the Hun! We beat the Updykes. We beat the unspeakables. A billion Chinese couldn't care less, but we do!

Monday, November 25, 2019

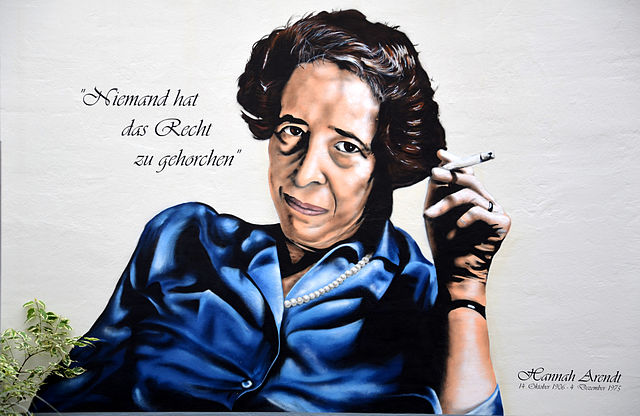

Arendt on Totalitarianism

Hannah Arendt Explains How Propaganda Uses Lies to Erode All Truth & Morality: Insights from The Origins of Totalitarianism

in History, Politics | January 24th, 2017 39 Comments

Advertisement

At least when I was in grade school, we learned the very basics of how the Third Reich came to power in the early 1930s. Paramilitary gangs terrorizing the opposition, the incompetence and opportunism of German conservatives, the Reichstag Fire. And we learned about the critical importance of propaganda, the deliberate misinforming of the public in order to sway opinions en masse and achieve popular support (or at least the appearance of it). While Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbelspurged Jewish and leftist artists and writers, he built a massive media infrastructure that played, writes PBS, “probably the most important role in creating an atmosphere in Germany that made it possible for the Nazis to commit terrible atrocities against Jews, homosexuals, and other minorities.”

How did the minority party of Hitler and Goebbels take over and break the will of the German people so thoroughly that they would allow and participate in mass murder? Post-war scholars of totalitarianism like Theodor Adorno and Hannah Arendt asked that question over and over, for several decades afterward. Their earliest studies on the subject looked at two sides of the equation. Adorno contributed to a massive volume of social psychology called The Authoritarian Personality, which studied individuals predisposed to the appeals of totalitarianism. He invented what he called the F-Scale (“F” for “fascism”), one of several measures he used to theorize the Authoritarian Personality Type.

Arendt, on the other hand, looked closely at the regimes of Hitler and Stalin and their functionaries, at the ideology of scientific racism, and at the mechanism of propaganda in fostering “a curiously varying mixture of gullibility and cynicism with which each member... is expected to react to the changing lying statements of the leaders.” So she wrote in her 1951 Origins of Totalitarianism, going on to elaborate that this “mixture of gullibility and cynicism... is prevalent in all ranks of totalitarian movements":

In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and nothing was true... The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that, under such conditions, one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.

Why the constant, often blatant lying? For one thing, it functioned as a means of fully dominating subordinates, who would have to cast aside all their integrity to repeat outrageous falsehoods and would then be bound to the leader by shame and complicity. “The great analysts of truth and language in politics”---writes McGill University political philosophy professor Jacob T. Levy---including “George Orwell, Hannah Arendt, Vaclav Havel—can help us recognize this kind of lie for what it is.... Saying something obviously untrue, and making your subordinates repeat it with a straight face in their own voice, is a particularly startling display of power over them. It’s something that was endemic to totalitarianism.”

Arendt and others recognized, writes Levy, that “being made to repeat an obvious lie makes it clear that you’re powerless.” She also recognized the function of an avalanche of lies to render a populace powerless to resist, the phenomenon we now refer to as “gaslighting”:

The result of a consistent and total substitution of lies for factual truth is not that the lie will now be accepted as truth and truth be defamed as a lie, but that the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world—and the category of truth versus falsehood is among the mental means to this end---is being destroyed.

The epistemological ground thus pulled out from under them, most would depend on whatever the leader said, no matter its relation to truth. “The essential conviction shared by all ranks,” Arendt concluded, “from fellow traveler to leader, is that politics is a game of cheating and that the ‘first commandment’ of the movement: ‘The Fuehrer is always right,’ is as necessary for the purposes of world politics, i.e., world-wide cheating, as the rules of military discipline are for the purposes of war.”

“We too,” writes Jeffrey Isaacs at The Washington Post, “live in dark times"---an allusion to another of Arendt’s sobering analyses—“even if they are different and perhaps less dark.” Arendt wrote Origins of Totalitarianism from research and observations gathered during the 1940s, a very specific historical period. Nonetheless the book, Isaacs remarks, “raises a set of fundamental questions about how tyranny can arise and the dangerous forms of inhumanity to which it can lead.” Arendt's analysis of propaganda and the function of lies seems particularly relevant at this moment. The kinds of blatant lies she wrote of might become so commonplace as to become banal. We might begin to think they are an irrelevant sideshow. This, she suggests, would be a mistake.

via Michiko Kakutani

Sunday, November 24, 2019

Confirming Kananaugh

Brett M. Kavanaugh, President Trump’s nominee to replace retiring Supreme Court Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, was never going to be confirmed by a wide or comfortable margin. The closely divided Senate, the still-bitter legacy of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s decision to block the nomination of Merrick Garland and the once-in-a-generation chance to cement a conservative majority for decades to come — all of these factors augured a nominee who would not win more than a few Democratic votes.

With the Senate split 51 to 49, Republicans had little margin for error; the loss of just two GOP votes would likely doom the nomination. The last-minute emergence of allegations that the nominee had sexually assaulted Christine Blasey Ford at a high school party on a summer night in 1982 threatened to derail the nomination. Wavering senators from both parties demanded an FBI investigation into the allegations by Ford and another woman, Deborah Ramirez, who said she recalled a drunken Kavanaugh exposing himself to her during their freshman year at Yale.

Ruth Marcus is deputy editorial page editor of The Post. This essay is adapted from her book, “Supreme Ambition: Brett Kavanaugh and the Conservative Takeover.”

Illustration by Lincoln Agnew for The Washington Post

The ensuing probe was less a hunt for the truth than a search for 51 votes — or 50; if it came to that, Vice President Pence could cast the deciding vote. Instead of following leads, the FBI ignored them. Agents interviewed only those individuals who the White House directed them to speak with. And the White House tasked the bureau with interviewing only those identified by the senators whose votes were needed to get the nominee across the finish line.

In the last stage of the confirmation battle, as at the start, Kavanaugh’s fate was largely in the hands of just two senators, Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. With their pro-choice views, they had always been the Republicans most likely to defect and vote against Kavanaugh. Now that volatile issues of gender and sexual assault had entered the debate, the pressure on both was even more intense. The two are best friends in the Senate — Collins’s husband, Tom Daffron, served as Murkowski’s chief of staff early in her Senate career — and they tend to vote as a unit. The motto in presidential politics has long been “As Maine goes, so goes the nation.” In the Kavanaugh fight, the governing assumption was that where Collins went, so would Murkowski. As a result, White House counsel Donald McGahn remained focused on Collins throughout. “The only way ever to convince Don of anything: Does Susan Collins need you to do that?” said one person who worked on the nomination.

At 65, Collins, who grew up in remote Caribou, in the northeast corner of the state, was part of a vanishing breed — a New England Republican. (There was only one other remaining, a House member from Maine, Bruce Poliquin, and he would lose to a Democrat in November 2018.) The fate of her fellow moderate Republicans was not lost on Collins, who is up for reelection in 2020 in a state that was trending increasingly Democratic. The odds on Collins, however, were always stacked in Kavanaugh’s favor. She had never opposed a Supreme Court nominee from a president of either party.

But neither could Collins be taken for granted, as Kavanaugh and his advisers well knew. She had her limits. She had written an op-ed for The Post in August 2016 announcing that she would not be voting for Trump. “This is not a decision I make lightly, for I am a lifelong Republican,” Collins wrote. “But Donald Trump does not reflect historical Republican values nor the inclusive approach to governing that is critical to healing the divisions in our country.” She cast a write-in vote for then-House Speaker Paul D. Ryan.

Once Trump was elected, Collins was more careful: Like every Republican lawmaker in the age of Trump, she had to protect herself from a primary challenge by Trump supporters intolerant of any deviations. Still, Collins on occasion — and on more occasions than most of her colleagues — had demonstrated her willingness to cross Trump. She voted against repealing the Affordable Care Act, against confirming Scott Pruitt to be administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency and against confirming Betsy DeVos to be secretary of education.

Collins’s father operated the family’s lumber mill in tiny Caribou (population 8,189 in 2010), though politics was the family business, as well. Both parents served as mayor; her father, grandfather and great-grandfather were elected to the state legislature. But the experience that defined Collins and best explained her approach to a decision as momentous as a Supreme Court confirmation was her dozen years as a staffer for another moderate Maine Republican, William Cohen.

Sens. Susan Collins (R-Maine), left, and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) at the U.S. Capitol on Oct. 3, 2018. (Drew Angerer)

Sens. Susan Collins (R-Maine), left, and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) at the U.S. Capitol on Oct. 3, 2018. (Drew Angerer)

Collins, then a government student at St. Lawrence University, applied for an internship with Cohen, a family friend and then a freshman congressman, during the fateful summer of 1974. Cohen sat on the House Judiciary Committee, which that July voted to approve articles of impeachment against Richard M. Nixon. Cohen was one of only a few Republicans who joined the Democratic majority. In a precursor to the thousands of coat hangers that would be sent to her office by Kavanaugh opponents, Cohen’s office, where one of Collins’s tasks was to open the mail, was deluged with letters containing tiny stones wrapped in paper: “Let him who is without sin cast the first stone.”

A quarter-century later, after following Cohen to the Senate and then being elected to his seat herself, Collins, then just a freshman senator, voted against convicting Bill Clinton in his Senate impeachment trial, one of only a few Republican senators to take that position. “In voting to acquit the president, I do so with grave misgivings for I do not mean in any way to exonerate this man,” Collins said. “He lied under oath; he sought to interfere with the evidence; he tried to influence the testimony of key witnesses.”

The speech was classic Collins. The former staffer had immersed herself in the facts against Clinton, painstakingly parsing the evidence against him. Then she pivoted to a nuanced assessment of the Senate’s constitutional role. Had she been a juror in a criminal obstruction-of-justice case against Clinton, Collins noted, she might well vote to convict him. But, she said, “as much as it troubles me to acquit this president, I cannot do otherwise and remain true to my role as a senator. To remove a popularly elected president for the first time in our nation’s history is an extraordinary action that should be undertaken only when the president’s misconduct so injures the fabric of democracy that the Senate is left with no option but to oust the offender from the office the people have entrusted to him.”

Looking back at Clinton’s impeachment was not a bad way of understanding Collins’s approach to complex issues: painstaking, methodical and conflicted. The best way to handle the sometimes prickly Mainer, Republicans knew, was to let Collins be Collins — not to lean on her, definitely not to threaten, but instead to ply her with briefings, with access to Kavanaugh and his supporters, as much as she wanted. She had a stubborn side, which would emerge in the course of the confirmation battle. Pushing her was bound to backfire, as McConnell (R-Ky.) understood. Better to kill her with kindness — or, better yet, information.

If Kavanaugh’s close connections to the Bush family had once been a nearly fatal liability, they were now a lifeline, perfectly calibrated to help him win the support of the one senator he needed most. Collins had long-standing ties to the Bush family and often visited them at their Maine retreat, in Kennebunkport. Alumni of the George W. Bush administration, establishment Republicans like Collins, were not shy about sharing with her their impressions of Kavanaugh, from the time he was nominated right up to the frantic close. Rob Portman of Ohio, her close friend in the Senate, who had worked with Kavanaugh in the White House, told her how impressively he had performed as staff secretary. She spoke with Karl Rove before she met with the nominee. And, perhaps most significant was that George W. Bush vouched enthusiastically for Kavanaugh.

Collins assembled a phalanx of advisers — including three lawyers who had worked for her, one of whom was Michael Bopp, a Washington attorney who had been her legislative director and general counsel — and a platoon of lawyers from the Congressional Research Service to assess Kavanaugh’s legal record and brief her on it. By Collins’s count, the roster of lawyers totaled 19. There were six study sessions with the CRS lawyers, plus seven meetings with the current and former staffers prepping her.

A nonlawyer, Collins nonetheless approached her meeting with the nominee as would an advocate preparing for oral argument, reading cases and law review articles. She immersed herself in issues such as severability (whether an entire law should fall if a particular provision is ruled unconstitutional, a critical question when it comes to the Affordable Care Act) and the constitutional dimensions of stare decisis. There was no courtesy call for which Kavanaugh prepared more intensively and none that lasted longer. The Aug. 21, 2018, session, attended by Collins’s legal brain trust, would stretch more than two hours, truncated only because Collins had to leave for a vote. “There were times when I think she felt that he was being a little too cautious and noncommittal, and I think she pressed as hard as she felt was responsible,” said Stephen Diamond, a former Collins staffer who attended the meeting. As the session broke up, Kavanaugh offered to wait around until Collins returned from the vote. His handlers “just looked at him with utter frustration on their faces, and said, ‘You’ve already spent twice as long with Sen. Collins as any other senator,’ ” Collins recalled.

TOP: Susan Collins walks to a room to read the report on the FBI investigation into Supreme Court nominee Brett M. Kavanaugh on Capitol Hill on Oct. 4, 2018. BOTTOM LEFT: Demonstrators protesting the nomination and possible confirmation of Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, rally across the street from the Portland, Maine, office of Susan Collins on Oct. 4, 2018. BOTTOM RIGHT: Boxes of letters from constituents sit on a table in the office of Kate Simson, state office representative for Susan Collins, in Portland on Oct. 4, 2018.

The investment paid off. Collins emerged from the meeting calling it “excellent” and touting Kavanaugh’s statement to her that Roe v. Wade was “settled law.” That, it seemed, would settle it for Collins.

From the point of view of Kavanaugh’s opponents, persuading Collins to vote against him presented a paradox. Pushing her too hard could boomerang, yet there was no way to persuade her to vote no without a significant public outcry, as much as she insisted she was immune to such tactics. For too long, some progressive activists in Maine thought, Collins had been treated with kid gloves, lavished with praise on the rare occasions when she did the right thing from the liberal point of view and never held to account when she marched in lockstep with the conservative majority.

This time would be different. Protesters dressed in “Handmaid’s Tale” costumes demonstrated outside her Bangor home. Even before Collins’s meeting with Kavanaugh, two progressive groups, Mainers for Accountable Leadership and Maine People’s Alliance, along with Ady Barkan, a health-care activist with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, announced plans for a crowdfunding effort to raise money for a to-be-named Collins opponent — if the senator voted for Kavanaugh. (The money would be returned to donors if Collins voted against the nominee.) The donations poured in, most in amounts of $20.20; by Sept. 12, just as the Ford story was beginning to break, the effort had raised more than $1 million. Collins was furious, calling the campaign “the equivalent of an attempt to bribe me.”

Meantime, the calls and letters flooding her Senate office at times crossed the line from angry to abusive, further alienating Collins. Her office was happy to supply details. There was the caller who left a voice mail saying, “If you care at all about women’s choice, vote no on Kavanaugh. Don’t be a dumb bitch.” In one episode that particularly upset Collins, a caller told a young female staffer that he hoped she would be raped and impregnated.

For all her public posture that she was immune to pressure tactics, the assault was beginning to take its toll. At one of the weekly Republican Senate lunches, the ads running against Collins were played on the screens in the room so that her colleagues had a sense of what she was up against. The others were mostly in safe red states; this was not a hard vote for them. For Collins, the politics were far more precarious. “For all of you here, it’s pretty easy, but in Maine they’re running commercials on me,” Collins told her colleagues. “You need to see what they’re doing.”

But if Collins was paying attention to the onslaught of ads, they were not having the effect that advocates had hoped. As the first round of hearings concluded, Collins made the decision that seemed fated all along. She would vote for Kavanaugh. The announcement was written, and she was prepared to deliver it just as the first hints of the Ford story began to emerge.

The pressure only heightened once the Ford story broke. Collins’s staff was fielding threats; one aide in Maine quit because she was so upset about the abuse. Collins struggled. She reached out to friends of Kavanaugh, including Lisa Blatt, a liberal Supreme Court advocate who had introduced Kavanaugh at the hearing, asking if they could imagine him doing anything like this. No, they assured her. Bush had called two days after the nomination; now he reached out again, two days after the Post story on Ford. Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s national security adviser, spoke with Collins the day after Ford’s testimony. And visiting the ailing George H.W. Bush at Kennebunkport, Collins saw Portman and longtime George W. Bush aide Joe Hagin, who had just left his position as deputy chief of staff at the Trump White House. As a Bush staffer, Hagin had spent weeks sharing a double-wide trailer with Kavanaugh at the ranch in Crawford, Tex. Could the person he knew so well have done such a thing? Inconceivable, he assured Collins.

From the opposite end of the country, Lisa Murkowski faced a set of political considerations in weighing the Kavanaugh nomination that made her political situation more similar to Collins’s than would be apparent at first glance, comparing purplish Maine to bright-red Alaska. Murkowski, 61, had been named by her father, Frank Murkowski, to fill his unexpired term when he became governor, in 2002. She won a close race for a full term in 2004, beating former Democratic governor Tony Knowles by just three points. Alaska was Republican territory: The only Democratic presidential candidate to win the state in the 15 elections held since it entered the union, in 1959, was Lyndon Johnson, in his 1964 landslide. While Trump lost Maine by three percentage points, his margin over Hillary Clinton in Alaska was 15 points. But the redness of the state did not dictate the contours of Alaskan politics when it came to Kavanaugh.

In the formative experience of her political career, Murkowski found herself blindsided in 2010 by a Sarah Palin-backed tea-party challenger named Joe Miller. When Miller, a little-known Fairbanks lawyer, unexpectedly beat Murkowski in the GOP primary that year by 2,006 votes, she pondered her options for three weeks, then mounted a write-in campaign against him. It was an uphill, and ugly, battle. National Republican leaders closed ranks behind Miller; GOP consultants and pollsters in the Lower 48 recoiled from working for Murkowski for fear of being blackballed. Murkowski was asked to resign from the Senate Republican leadership. “I informed her that by choosing to run a campaign against the Republican nominee, she no longer has my support for serving in any leadership roles,” McConnell said at the time. No senator had won election as a write-in candidate since South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond in 1954, and Murkowski had the extra challenge of teaching voters to spell her name correctly.

Two groups propelled Murkowski to her improbable victory:: Native Americans and women. They again played a central role, eight years later, in the Kavanaugh battle. The Alaska Federation of Natives announced its opposition to Kavanaugh on Sept. 12, just before the Ford story broke, criticizing what it saw as Kavanaugh’s hostility toward federal protection of tribes. Hawaii Sen. Mazie Hirono (D) had deliberately laid the groundwork for this opposition in her questioning of Kavanaugh. The subject matter was arcane — the contours of the Indian commerce clause and the legal status of Alaska Natives — but Hirono’s questioning was microtargeted at an audience of one. She never lobbied Murkowski directly, but she knew her colleague would be listening closely.

Women’s groups in Alaska — in particular, abortion-rights activists — were geared up from the start to battle Kavanaugh. With the emergence of the Ford allegations, that opposition kicked into higher, and more emotional, gear with last-minute meetings that would, in the end, help Murkowski come to a final decision on what she described as perhaps the closest call of her Senate career.

An arcane bit of Senate procedure set the stage for the conclusion of the fight. On Wednesday evening, Oct. 3, McConnell filed a motion to invoke cloture on the Kavanaugh nomination. That meant the first hurdle would be a vote Friday morning to end debate on the nomination — the critical test of whether Kavanaugh would have the 50 votes he needed. Early the next morning, around 2:30, the FBI submitted its report on Kavanaugh and delivered the material to the Senate. The interview summaries totaled 45 pages, and there were an additional 1,600 pages of information from the FBI tip line. Only 109 people would have access to the documents — the senators, four staffers each from the majority and minority, and a committee clerk.

Lisa Murkowski speaks to reporters after voting "no" on the Senate procedure cloture vote to confirm Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court on Oct. 5, 2018. (Melina Mara/The Washington Post)

Lisa Murkowski speaks to reporters after voting "no" on the Senate procedure cloture vote to confirm Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court on Oct. 5, 2018. (Melina Mara/The Washington Post)

Republicans and Democrats took turns reading the documents, with control of the room rotating every hour. There was only a single copy of the material, divided among a dozen folders, which made digesting it all the more difficult. During Republicans’ early hours in the room, the Judiciary Committee staff read out loud from the materials. Democrats divided up the material among themselves, passing around the sections and discussing the most relevant parts.

Republicans had developed something of a buddy system, with Kavanaugh proponents shadowing the wavering members. Jeff Flake of Arizona and Mike Lee of Utah spent much of the day together in the Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility, studying the report. “So, I’m a yes,” Lee told his friend. Flake agreed. He said he, too, would vote to confirm. Ohio’s Rob Portman spent much of his time in the SCIF with Collins, who attended a staff briefing in the morning and returned later to read through the material herself. In another piece of good news for Kavanaugh, West Virginia’s Joe Manchin III, a Democrat, indicated privately that he planned to vote yes, though it would be another 24 hours before that became public. Collins and Murkowski were the wild cards, although with Manchin seemingly in favor, and Collins predisposed to Kavanaugh, things were looking good. “It appears,” she observed, “to be a very thorough investigation.” Said Flake, “Thus far, we’ve seen no new credible corroboration. No new corroboration at all.”

Democrats had a dramatically different interpretation. “The most notable part of this report is what’s not in it,” Dianne Feinstein of California said. Illinois’s Richard J. Durbin was in the SCIF with more than a dozen fellow Democrats that afternoon, sitting next to Maryland’s Ben Cardin as they read through the reports. “Obvious questions and lines of inquiry were not followed,” Durbin said later. “Witnesses would say they had a spotty recollection but suggest someone else to speak with, but it just seemed like they were determined to do the requisite number, end the interviews, be finished. It was a real disappointment.”

In hindsight, there are two ways to think about the FBI investigation. The rosier, more charitable view is that, for all its manifest limitations, at least the insistence on a pause and an investigation signaled to women across the country that their allegations would be taken seriously, that their complaints would no longer be brushed aside. Some progress, in this view, was better than none at all. The more negative, and perhaps more accurate, assessment is that the FBI investigation was, as Trump had predicted, “a blessing in disguise” for Republicans. As much as they had resisted the probe, it served to give Kavanaugh’s confirmation an aura of legitimacy that it would not otherwise have had.

As Republicans and Democrats shuttled in and out of the SCIF to review the FBI materials, Murkowski met in her office with Alaskan women who had flown to the capital, a journey underwritten by the American Civil Liberties Union, for a last-ditch lobbying campaign. The ACLU did not routinely wade into the judicial nominations wars, but it had departed from that policy in several past circumstances, opposing William H. Rehnquist, Robert H. Bork and Samuel A. Alito Jr. This, the group decided in the wake of the Ford allegations, was another of those “extraordinary circumstances.” Casey Reynolds of the Alaska ACLU received a call from the national organization: We can give you $100,000 to get Alaskans to Washington. Then, as dozens of Alaskan women clamored to be included, it came up with another $100,000.

There was some reason to think Murkowski might be receptive to their arguments. In the week before Ford’s testimony, Liz Ruskin, a reporter for Alaska Public Media, had asked Murkowski whether she had experienced her own #MeToo moment. “She answered with an immediate and emphatic ‘yes,’ ” Ruskin reported. “And that’s about all she wanted to say about that.” The Kavanaugh confirmation, Murkowski said then, had transcended the question of his qualifications. “We are now in a place where it’s … about whether or not a woman who has been a victim at some point in her life is to be believed.”

About 120 women came from Alaska to the capital to make the case against confirming Kavanaugh. Murkowski met with two groups of them on Thursday afternoon, about 18 each.

The first were female lawyers, organized by an Anchorage attorney, Michelle Nesbett, who crowded into a room in Murkowski’s fifth-floor office in the Hart Senate Office Building. As the women gathered around the table and perched on the arms of a couch, protesters thronging the building’s atrium could be heard shouting about Kavanaugh. The lawyers’ argument was not about Kavanaugh’s ideology or even his alleged assault of Ford. It was that Kavanaugh’s conduct in his testimony demonstrated an alarming absence of judicial temperament. Nesbett handed Murkowski a copy of the American Bar Association’s Code of Judicial Conduct, Rule 1.2, which provides that “a judge should act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary.” How could anyone who watched Kavanaugh believe he had done that? Murkowski seemed relieved that the lawyers were not haranguing her about Kavanaugh’s position on Roe v. Wade or native rights.

One of those present was Moira Smith, an Anchorage lawyer who had, after the release of Trump’s “Access Hollywood” tape, accused Justice Clarence Thomas of groping her at a 1999 dinner party. “We already have one person who has the cloud of sexual harassment allegations on the court,” Smith said. “I don’t think we as a country would be well-served to have another.” Another woman, Carolyn Heyman, became teary-eyed as she told Murkowski that one of her daughters asked why women were believed less than men after Ford came forward. Nesbett was forceful. “You cannot vote to confirm this guy,” she told Murkowski. “If you do so, it will be a betrayal to the women of Alaska.”

The next meeting, with women who had been victims of sexual assault, was even more powerful — it stretched to well over an hour as woman after woman described her experience and talked about the terrible message that confirming Kavanaugh would send. One, an Alaska Native, described how she and nearly every other woman in her family — her mother, her aunt, her sisters — had been the victim of rape. Another brought photos of her baby daughter, saying that she herself had been sexually assaulted and did not want her daughter raised in a society where such actions have no consequences. Still another described having been the victim of a date rape in high school, how she had not filed a complaint because it would have been his word against hers, and how believable she found Ford. Murkowski mentioned her own #MeToo moment, without elaborating. She seemed burdened, almost devastated. “I feel six inches shorter than when I walked in here,” Murkowski told the women as the meeting broke up. “I’m so humbled by all of your stories.”

At 10:30 that night, she headed back to the SCIF to take one last look at the FBI report.

By the time a nomination makes it to the Senate floor, the outcome is almost always a foregone conclusion. With Kavanaugh, the situation was more precarious. “This was one of the rare instances where I didn’t know,” Texas Sen. John Cornyn, the Republican whip, said. The cloture vote set for the morning would almost certainly signal the final outcome.

Collins had been up until 2 a.m. working on her floor speech. Five hours later, the protesters who had been gathering outside her Capitol Hill townhouse for days now began their chanting. Collins checked in with Murkowski, to tell her she planned to vote for Kavanaugh. Murkowski responded that she was still undecided. The Alaskan would later tell colleagues that she hadn’t known for sure until she walked onto the Senate floor how she would vote. With the roll call set for 10:30 a.m., the chamber was filling up. Murkowski arrived slightly before Collins. The pair sat in their usual seats, side by side, third row from the front, just across the aisle from the Democrats. Murkowski reached over and touched Collins on the arm. “I just want you to know that I can’t vote for him,” she said.

The Maine senator broke into a huge smile. “That’s great,” Collins said. “I have to admit, I’m relieved.”

“No, you misheard me,” Murkowski corrected her. “I said I’m not voting for him.”

The clerk called the roll, in alphabetical order. Yes, Collins said. When it came to Murkowski, she stood and paused. Her voice was barely above a whisper as she voted: “No.” Murkowski sat down, expressionless. She and Collins sat side by side, hands clasped in their laps, stone-faced. Toward the end of the vote, Collins leaned toward Murkowski, putting her hand on the Alaskan’s chair as the two spoke.

Collins’s vote on cloture was a major signal but not an ironclad guarantee. There had been times in the past when Collins would support getting a controversial nominee or piece of legislation to the floor only to oppose it on final passage. She would explain herself, and outline her final position, in a floor speech at 3 p.m.

Collins headed to the Senate Dining Room for what she thought would be a solo lunch, holding a copy of the speech she had stayed up writing until early that morning. McConnell and Cornyn waved her over; did she want to join them? “I think they were all exercising great control,” not asking her what she would do, Collins recalled. “And so I told them that I had decided to vote for Judge Kavanaugh and that I felt that it was the right thing to do.”

For anyone who was still in suspense about how Collins would come down, her floor speech sealed the deal. “Today,” Collins said, “we have come to the conclusion of a confirmation process that has become so dysfunctional, it looks more like a caricature of a gutter-level political campaign than a solemn occasion.” She inveighed against a process that had become so partisan that interest groups decried the nominee even before his identity became known. She ticked through the substantive questions about Kavanaugh — whether he would overturn protections for people with preexisting conditions, whether he would rule reflexively for Trump, whether he would jettison Roe v. Wade — and dismissed each in turn.

Kavanaugh had not only assured her of his respect for precedent and reluctance to overturn it, Collins emphasized, he had also located the command of such reluctance, stare decisis, within the Constitution itself — an approach that, Collins asserted, provided additional assurance that Kavanaugh would not be overturning cases on a whim. Those who disagreed had been proved wrong in the past, Collins said, citing the buttons that the National Organization for Women circulated in 1990 — STOP SOUTER Or WOMEN WILL DIE.

As to the Ford allegations, Collins said, “the Senate confirmation process is not a trial. But certain fundamental legal principles about due process, the presumption of innocence, and fairness do bear on my thinking, and I cannot abandon them. In evaluating any given claim of misconduct, we will be ill served in the long run if we abandon the presumption of innocence and fairness, tempting though it may be.”

Collins turned opponents’ argument that confirming Kavanaugh would undermine confidence in the judiciary on its head. “The presumption of innocence is relevant to the advice and consent function when an accusation departs from a nominee’s otherwise exemplary record,” Collins said. “I worry that departing from this presumption could lead to a lack of public faith in the judiciary and would be hugely damaging to the confirmation process moving forward.”

As to Ford, Collins acknowledged, her testimony was “sincere, painful and compelling,” adding, “I believe that she is a survivor of a sexual assault and that this trauma has upended her life.” But she said she was disturbed by the fact that none of the others Ford identified as having been present could corroborate her account.

Key moments from Sen. Collins’s speech, in three minutes

“The facts presented do not mean that Professor Ford was not sexually assaulted that night — or at some other time — but they do lead me to conclude that the allegations fail to meet the ‘more likely than not’ standard,” Collins said. “Therefore, I do not believe that these charges can fairly prevent Judge Kavanaugh from serving on the court.”

She ended with a plea that seemed disengaged from the reality of the moment. “Despite the turbulent, bitter fight surrounding his nomination,” Collins concluded, “my fervent hope is that Brett M. Kavanaugh will work to lessen the divisions in the Supreme Court so that we have far fewer 5-4 decisions and so that public confidence in our judiciary and our highest court is restored.”

As Collins spoke, Kavanaugh and several clerks had gathered in his chambers, which had no television and balky WiFi. So rather than watching her live, they were reduced to following what she was saying — and learning the final verdict — via text messages from another clerk, who was relating Collins’s comments in real time.

Republican praise for Collins poured in, many comparing her to Margaret Chase Smith, the moderate Maine Republican renowned for being among the first to stand up to Joseph McCarthy. There were many things to admire about Collins’s handling of the nomination. She had devoted more time to assessing Kavanaugh’s record and spoken to more people about the nominee than any senator not on the Judiciary Committee and perhaps more than some who served on the panel. But it was difficult, listening to Collins, to escape the notion that the entire enterprise had been geared to an inevitable conclusion. She consistently assessed every piece of evidence in the light most favorable to Kavanaugh.

After Collins finished, McConnell led Republicans in a standing ovation.

Murkowski returned Friday evening to the Senate chamber, now nearly empty, to explain her vote in what she described as the “gut-wrenching” process of the Kavanaugh nomination. In a somber voice, she said, in the end, she was not opposing Kavanaugh because she feared he would vote to overturn Roe v. Wade, strip protections for people with preexisting conditions, or pose a threat to the rights of Alaska Natives. Kavanaugh was a “learned judge,” she said, and a “good man.” But his appearance before the committee had rattled her and made her doubt that he had met the standard in the code of judicial conduct, which stipulates that a judge should “act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence.” Public confidence, Murkowski repeated, in a soft, pained voice. “Where’s the public confidence?”

Murkowski said she had been “deliberating, agonizing about what is fair. Is this too unfair a burden to place on somebody that is dealing with the worst, the most horrific allegations that go to your integrity, that go to everything that you are? And I think we all struggle with how we would respond.”

But, she said, “I am reminded there are only nine seats on the bench of the highest court in the land. … With my conscience, I could not conclude that he is the right person for the court at this time. And this has been agonizing for me with this decision. It is as hard a choice, probably as close a call, as any that I can ever remember.”

When Kavanaugh’s nomination came up for final passage the next day, Murkowski said, she would be voting “present,” not against the nomination. It was not a statement on the merits but a token of friendship — pairing her vote against that of a colleague who disagreed so they would cancel each other out — to accommodate Montana Republican Steve Daines, whose daughter was being married that day. “At just about the same hour that we’re going to be voting, he’s going to be walking his daughter down the aisle, and he won’t be present to vote, and so I have extended this as a courtesy to my friend,” Murkowski said. “It will not change the outcome of the vote, but I do hope that it reminds us that we can take very small, very small steps to be gracious with one another, and maybe those small, gracious steps can lead to more.” It was a brief moment of decency in an otherwise ugly process.

As Murkowski concluded her remarks, there was no applause.

The outcome was as expected: 50 to 48. It was the closest margin for a successful nominee since the little-known Stanley Matthews was confirmed in 1881 by a vote of 24 to 23, the closest in history. “I always thought landslides were kind of boring anyway,” McConnell said later.

Colleagues gathered around Collins after she cast her vote. “Well, they’re going to come after me with everything they can get,” she said. “You don’t worry,” Lindsey O. Graham of South Carolina replied. “We’ve got Sheldon Adelson as chairman of your campaign finance committee,” he said, referring to the Las Vegas casino billionaire who was the GOP’s most generous donor. Collins was all but certain to have a tough race on her hands in 2020, tougher now with the Kavanaugh vote. She sometimes exasperated her colleagues and sometimes disappointed them. On Kavanaugh, however, she had delivered. The party — and its financiers — would not forget.

It had taken 101 days from Anthony M. Kennedy’s retirement to Brett M. Kavanaugh’s confirmation, but the effects of the vote would reverberate long after — for the political parties, for the individuals involved and for the court itself.

In an interview with The Post hours before Kavanaugh’s near-certain confirmation, McConnell was jubilant — not only because Kavanaugh was making it through but also because the politics of the nomination battle were looking like a welcome electoral plus for Republicans. “It’s been a great political gift for us,” McConnell said. “I want to thank the mob, because they’ve done the one thing we were having trouble doing, which was energizing our base.”

McConnell had even more reason to celebrate on Election Day, when voters ousted four incumbent Senate Democrats who voted against Kavanaugh. What was less clear was the degree to which the Kavanaugh vote determined those outcomes or whether those senators were already destined to lose, their opposition to Kavanaugh simply hammering another nail in an already closed coffin.

Collins was not up for reelection that November, but there was every indication that she was taking the 2020 race seriously — and that Graham’s promise that the party would take care of her was bearing fruit. A group of Kavanaugh supporters held an emotional fundraiser for Collins the month after the confirmation vote. Collins told the group that the police in Maine had stationed a dummy car outside her home for protection; McConnell stopped by to express his support. By the end of June 2019, Collins had collected an impressive $6.45 million — as much as she had raised in her entire previous campaign, with 16 months to go. An astonishing 96 percent of the money came from out of state, compared with 69 percent during her prior race. Adelson and his wife, Miriam, contributed the maximum amount, $11,200 combined. And Federalist Society chief Leonard Leo hosted a fundraiser for Collins in August 2019 at his summer home in Maine.

But Collins’s Kavanaugh vote had taken a toll on her popularity. A few days after the Leo event, the Cook Political Report changed its assessment of the Maine Senate race from “lean Republican” to “toss-up."

Collins’s vote for Kavanaugh assured him the Supreme Court seat he had sought for decades. It remained to be seen whether the events of 2018 would cost the Maine Republican her own Senate seat in 2020. Murkowski will not face reelection until 2022.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)