by Paul Krugman

Saturday, February 28, 2015

No Dress Rehearsal

This is not a dress rehearsal for your life. I repeat: this is NOT a

dress rehearsal. As they say in the movie business, this is a hot set.

This life is a live take. Whatever you do from here on out do not

assume there will be any do-overs. Try & get it right the first

time.

Friday, February 27, 2015

Hooray for Print!

Sorry, Ebooks. These 9 Studies Show Why Print Is Better

The Huffington Post

|

By

Maddie Crum

Younger people are more likely to believe that there's useful information that's only available offline.

While 62 percent of citizens under 30 subscribe to this belief, only 53 percent of those 30 and older agree. These findings are from a promising study released last year by Pew Research, which also found that millennials are more likely to visit their local library.

Students are more likely to buy physical textbooks.

A study conducted by Student Monitor and featured in The Washington Post shows that 87 percent of textbook spending for the fall 2014 semester was on print books. Of course, this could be due to professors assigning less ebooks. Which is why it's fascinating that...

Students opt for physical copies of humanities books, even when digital versions are available for free.

While students prefer reading digital texts for science and math classes, they like to study the humanities in print. A study conducted by the University of Washington in 2013, and quoted in The Washington Post, shows that 25 percent of humanities students bought physical versions of free ebooks.

This isn't just true of textbooks. Teens prefer print books for personal use, too.

Nielson BookScan numbers from 2014 revealed the main reasons why teens buy books: "I've enjoyed author's previous books" ranked No. 1, followed by "browsing in libraries" and "browsing in bookstores," which both ranked above "online bookseller websites." "In-store displays" also ranked above hearing about a book through a social network.

Students don't connect emotionally with on-screen texts.

A 2012 study featured in the Guardian gave half its participants a story on paper, and the other half the same story on screen. The result? iPad readers didn't feel that the story was as immersive, and therefore weren't able to connect with it on an emotional level. Further, those who read on paper were much more capable of placing the story's events in chronological order.

... And they comprehend less of the information presented in digital books.

USA Today shared a 2013 study showing that students retain less when reading on a screen. The study's creator blamed this on the "flash gimmicks" embedded in many ebooks. She also suspects being able to collectively turn to the same page enhances group discussion.

It's not just students opting for print. Parents and kids prefer to read physical books together, too.

According to Digital Book World and literacy nonprofit Sesame Workshop, less than ten percent of kids and parents alike choose ebooks over print books. Parents say fancy features such as videos and interactive games are more of a distraction than a valued tool.

Which makes sense, because ebooks can negatively impact your sleep.

A few months ago, the Guardian reported on a Harvard study linking e-reading and sleep deprivation. If the ebook was "light emitting" it took participants an average of ten minutes longer to fall asleep than those who read physical books instead.

... And it's hard to avoid multitasking while reading digital books.

In a blog for The Huffington Post, Naomi S. Baron wrote about the findings published in her new book, Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World. "Studies I have done with university students in several countries confirm what I bet you'll find yourself observing," she writes. "When reading either for (school) work or pleasure, the preponderance of students found it easiest to concentrate when reading in print. They also reported multitasking almost three times as much when reading onscreen as when reading in hard copy."

Do you prefer print books to ebooks? Tweet @HuffPo

No Fooling

You can fool all of the people some of the time, and you can fool some

of the people all of the time, but you can't fool all of the people all

of the time, even if your name is Bill O'Reilly.

Wednesday, February 25, 2015

In Like Flint

I am in like Flint, home bound due to inclement weather, the hacienda

locked down tight. I'm afraid to go out today. My luck is that I would

end up stranded in Tim-Buck-Too with no way to get back home. I got

lunch meat in the ice box and canned tuna in the pantry. I got Drew

Carey and The Price is Right on the TV. I ain't complaining.

Monday, February 23, 2015

The Fiduciary Rule

Mon Feb 23, 2015 at 07:58 AM PST

White House, Elizabeth Warren team up to protect retirement savings from Wall Street

What will that mean in practice? When workers or retirees rollover their savings accounts, typically 401(k)s, into IRAs, brokers will generally not be able to recommend products that give them a kickback but diminish the clients long-term yield. The new fiduciary standard should block what honest brokers call "over-managing:" unnecessary rollovers, churning (over-active buying and selling that generates brokers' fees at the expense of returns), and the pushing of expensive and risky products like variable annuities.Not surprisingly, Wall Street, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and lawmakers from both parties are gearing up to fight the rule. David Dayen points to a a letter the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, a large trade group, got 183 members of Congress to sign, "including 118 Democrats, attacking the Labor Department rule." You can expect a Republican Congress, with the help of some Democrats, to act swiftly to try to find a way to block or blunt these rules. The Department of Labor has created a website where you can read more background about the proposed rule and how to protect retirement savings.

Originally posted to Joan McCarter on Mon Feb 23, 2015 at 07:58 AM PST.

Saturday, February 21, 2015

The Loft

It's an okay movie, certainly not great, but worth it at the discount house on Lorna Road. The plot is too complicated. There is a twist at the end though not so great a twist. On my new scale of 1 to 6 I give it a #3.

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Emerson

In the highest civilization the book is still the highest delight.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson from "Quotation and Originality"

-Ralph Waldo Emerson from "Quotation and Originality"

Sunday, February 15, 2015

Word of the Week

CONVIVIAL

Meaning: Friendly, enjoyable, lively.

(Of a person) Cheerful. Friendly, Jovial.

Meaning: Friendly, enjoyable, lively.

(Of a person) Cheerful. Friendly, Jovial.

Richard Wightman Fox - Lincoln's Body

Abraham Lincoln is a man about whom it can truly be said that the last word will never be written. Here is a proof: a book that uses Lincoln's body, called ugly and hideous in his lifetime, as a metaphor to present a cultural history of the man. And doubt it not. This is a portrait of the good Lincoln.

"Richard Wightman Fox has ingeniously portrayed the physical body of Abraham Lincoln, living and dead, in his own time and in memory, as a vehicle for evaluating Lincoln's continuing impact on American culture." James M. McPherson (inside cover)

The book borders on hagiography. Lincoln the Renaissance Man. Lincoln the President who could have led the country thru Reconstruction and the industrial age that followed the war. Lincoln the man who could do no wrong.

Lincoln died from the bullet of John Wilkes Booth after speaking of granting limited suffrage to "qualified" blacks in Louisiana. Therefore, the "open-minded" A. Lincoln was moving in a liberal direction toward Reconstruction at the time of he death. Had he lived, he and the Radical Republicans would have done great things to push political freedom forward in the country. Well, maybe. P. 23

The author seems to say that the Radical Republicans were glad that Lincoln had died. This is surprising to me.

The author describes the chaos that followed the assassination. Did Bates really say "now he belongs to the ages?"

The Lincoln Cult from the 1860's to the 1960's. P. 97

Holland's biography published in 1866 fueled the Lincoln cult. P. 98

The story of the funeral train with its 1,700 trek from DC to Springfield is a full story in itself.

Stanton micromanaged events after the assassination. P. 103

Whitman's two poems about Lincoln were popular from the beginning. P. 127

George Bancroft was a states rights Democrat. P. 130

"Richard Wightman Fox has ingeniously portrayed the physical body of Abraham Lincoln, living and dead, in his own time and in memory, as a vehicle for evaluating Lincoln's continuing impact on American culture." James M. McPherson (inside cover)

The book borders on hagiography. Lincoln the Renaissance Man. Lincoln the President who could have led the country thru Reconstruction and the industrial age that followed the war. Lincoln the man who could do no wrong.

Lincoln died from the bullet of John Wilkes Booth after speaking of granting limited suffrage to "qualified" blacks in Louisiana. Therefore, the "open-minded" A. Lincoln was moving in a liberal direction toward Reconstruction at the time of he death. Had he lived, he and the Radical Republicans would have done great things to push political freedom forward in the country. Well, maybe. P. 23

The author seems to say that the Radical Republicans were glad that Lincoln had died. This is surprising to me.

The author describes the chaos that followed the assassination. Did Bates really say "now he belongs to the ages?"

The Lincoln Cult from the 1860's to the 1960's. P. 97

Holland's biography published in 1866 fueled the Lincoln cult. P. 98

The story of the funeral train with its 1,700 trek from DC to Springfield is a full story in itself.

Stanton micromanaged events after the assassination. P. 103

Whitman's two poems about Lincoln were popular from the beginning. P. 127

George Bancroft was a states rights Democrat. P. 130

The Paul Ryan Delusion

Jonathan Chait notes that people are still trying to cast Paul Ryan as reasonable and moderate — hey, he visits bookstores favored by liberals. As Chait says, this sort of political evaluation by personal style is unreliable at best; and Ryan quite clearly deliberately exploits it, too, making moderate noises without ever giving an inch on his hard-line right-wing policies. Remember, this is the guy who pretended to offer a budget based on fiscal responsibility, but when you took out the magic asterisks it was really tax cuts for the rich, severe benefit cuts for the poor, and overall would actually increase the deficit.

I would add that Ryan isn’t just exploiting the press corp’s preference for up-close-and-personal over policy analysis; he’s also exploiting the eternal search for a Serious, Honest, Conservative, a creature centrists know must be out there somewhere (because otherwise their centrism is a colossal error of judgment).

But let’s not make this just about Ryan, or even about conservatism (although conservatives have been the main beneficiaries of the up-close-and-personal syndrome.) The fact is that attempts to judge politicians by how they come across have been almost universally disastrous during my whole tenure at the Times. Younger readers may not remember the days when George W. Bush was universally portrayed in the press as a bluff, honest, guy; those of us who pointed to his lies about taxes and Social Security and suggested that these were a better guide to his character than how he came across got nowhere until years later. John McCain rode for many years on a reputation as a principled maverick, because that’s the way he talked; I think his shameless embrace of every right-wing twist and turn has dented that reputation, but he’s still the darling of Sunday morning talk.

And then, of course, there was the irrefutable case for invading Iraq, irrefutable because Colin Powell made it, and only a fool or a Frenchman could fail to be persuaded. Or, maybe, someone who asked what actual evidence Powell had presented and noticed that there wasn’t any.

Meanwhile, some public figures face the reverse treatment, portrayed as evil and devious because reporters have decided that this is how they come across. E.g., Hillary Clinton, whose harsh treatment by the press has nothing to do with her gender, no way, no how. Or Mitt Romney, portrayed as smarmy and unlikable because — well, actually, he really is smarmy and unlikable, but you should reach that judgment based on his policies, not his persona.

Back to Ryan: the really amazing thing about the persistence of his personality cult is that economic and budget policy is his chosen area, where he has left a broad paper trail. So there is plenty of evidence about what he really believes and stands for, every bit of which says that his overriding goal is to redistribute income from the poor to the one percent. If you want to claim otherwise, show me anything — anything at all — in his policy proposals that doesn’t go in that direction.

On Slavery

Sunday, Feb 15, 2015 07:00 AM CST

(Credit: Stocksnapper via Shutterstock)

(Credit: Stocksnapper via Shutterstock)

Should a person be able to own another person? Today Christians

uniformly say no, and many would like to believe that has always been

the case. But history tells a different story, one in which Christians

have struggled to give a clear answer when confronted with questions

about human trafficking and human rights. Had the Bible been edited

differently, Christendom might have achieved moral clarity on this issue

sooner. As is, the Bible contains very mixed messages, which means that

biblical authority could be invoked on either side of the question,

leaving Christian beliefs about slavery vulnerable for centuries to

prevailing cultural, political, and economic currents.

Should a person be able to own another person? Today Christians

uniformly say no, and many would like to believe that has always been

the case. But history tells a different story, one in which Christians

have struggled to give a clear answer when confronted with questions

about human trafficking and human rights. Had the Bible been edited

differently, Christendom might have achieved moral clarity on this issue

sooner. As is, the Bible contains very mixed messages, which means that

biblical authority could be invoked on either side of the question,

leaving Christian beliefs about slavery vulnerable for centuries to

prevailing cultural, political, and economic currents.

Old Testament Endorses, Describes, and Regulates Slavery

The Bible first endorses slavery in the book of Genesis, in the story of Noah the ark builder. After the flood, Noah’s son Ham sees his father drunk and naked, and for reasons that have long been debated, is cursed. One recurring theme in Genesis is that guilt can be transferred from a guilty person to an innocent person (think of Adam and Eve’s fruit consumption, which taints us all), and in this case the curse is put on Ham’s son, Canaan.

When Noah awoke from his wine and knew what his youngest son had done to him, he said, “Cursed be Canaan; lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers.” He also said, “Blessed by the Lord my God be Shem; and let Canaan be his slave. May God make space for Japheth, and let him live in the tents of Shem; and let Canaan be his slave.” Genesis 9:24-27 NRSV

Most likely, this story was intended originally to justify the Israelite subjugation of Canaanite peoples, who, in other stories about the conquest of the Promised Land are slaughtered or enslaved. Later though, Christians and Muslims would use the story to explain why some people have dark skin, and “Ham’s curse” became a justification for enslaving Native Americans and Africans.

Throughout the Hebrew Old Testament, slavery is endorsed in a variety of ways. Patriarchs Abraham and Jacob both have sex with female slaves, and the unions are blessed with male offspring. Captives are counted among the booties of war, with explicit instructions given for purifying virgin war captives before “knowing them.” The wisest man of all time, Solomon, keeps hundreds of concubines, meaning sexual slaves, along with his many wives.

Where the Bible really stands on slavery

Valerie Tarico, AlterNet (Credit: Stocksnapper via Shutterstock)

(Credit: Stocksnapper via Shutterstock)

This article originally appeared on AlterNet.

Should a person be able to own another person? Today Christians

uniformly say no, and many would like to believe that has always been

the case. But history tells a different story, one in which Christians

have struggled to give a clear answer when confronted with questions

about human trafficking and human rights. Had the Bible been edited

differently, Christendom might have achieved moral clarity on this issue

sooner. As is, the Bible contains very mixed messages, which means that

biblical authority could be invoked on either side of the question,

leaving Christian beliefs about slavery vulnerable for centuries to

prevailing cultural, political, and economic currents.

Should a person be able to own another person? Today Christians

uniformly say no, and many would like to believe that has always been

the case. But history tells a different story, one in which Christians

have struggled to give a clear answer when confronted with questions

about human trafficking and human rights. Had the Bible been edited

differently, Christendom might have achieved moral clarity on this issue

sooner. As is, the Bible contains very mixed messages, which means that

biblical authority could be invoked on either side of the question,

leaving Christian beliefs about slavery vulnerable for centuries to

prevailing cultural, political, and economic currents.Old Testament Endorses, Describes, and Regulates Slavery

The Bible first endorses slavery in the book of Genesis, in the story of Noah the ark builder. After the flood, Noah’s son Ham sees his father drunk and naked, and for reasons that have long been debated, is cursed. One recurring theme in Genesis is that guilt can be transferred from a guilty person to an innocent person (think of Adam and Eve’s fruit consumption, which taints us all), and in this case the curse is put on Ham’s son, Canaan.

When Noah awoke from his wine and knew what his youngest son had done to him, he said, “Cursed be Canaan; lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers.” He also said, “Blessed by the Lord my God be Shem; and let Canaan be his slave. May God make space for Japheth, and let him live in the tents of Shem; and let Canaan be his slave.” Genesis 9:24-27 NRSV

Most likely, this story was intended originally to justify the Israelite subjugation of Canaanite peoples, who, in other stories about the conquest of the Promised Land are slaughtered or enslaved. Later though, Christians and Muslims would use the story to explain why some people have dark skin, and “Ham’s curse” became a justification for enslaving Native Americans and Africans.

Throughout the Hebrew Old Testament, slavery is endorsed in a variety of ways. Patriarchs Abraham and Jacob both have sex with female slaves, and the unions are blessed with male offspring. Captives are counted among the booties of war, with explicit instructions given for purifying virgin war captives before “knowing them.” The wisest man of all time, Solomon, keeps hundreds of concubines, meaning sexual slaves, along with his many wives.

The books of the Law provide explicit rules for the treatment of Hebrew and non-Hebrew slaves.

New Testament Encourages Kindness from Master, Obedience from Slave

Equally regrettable, from the standpoint of moral clarity, is the fact that New Testament writers fail to condemn Old Testament slavery. In fact, the Jesus of Matthew says that he has come not to abolish the Law but to fulfill it: “For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is accomplished” (Matthew 5:18).

Slavery comes up regularly in New Testament texts; but rather than repudiating the practice, the writers simply encourage good behavior on the part of both slaves and masters. Slaves are clearly property of the owners, as are their families. In one parable Jesus compares God to a king who has slaves. When one slave refuses to forgive the debt of a peer, the righteous king treats him in kind, “and, as he could not pay, his lord ordered him to be sold, together with his wife and children and all his possessions, and payment to be made” (Matthew 18:25).

While in prison, the Apostle Paul encounters an escaped slave, Onesimus, and sends a letter to his Christian owner, Philemon, tacitly endorsing Philemon’s authority in the matter. The messages are mixed. Paul sends Onesimus back to Philemon “not as a slave but as a brother”—but he does send him back.

Several letters attributed to Paul express the sentiment that in Christ all people are one:

Church Fathers Disagree but Pro-Slavery Faction Dominates for 1300 Years

For some early Christians, the message of equality trumped endorsements of slavery. John Fletcher (Lessons on Slavery, 1852) wrote that early sects in Asia Minor “decried the lawfulness of it, denounced slaveholding as a sin, a violation of the law of nature and religion. They gave fugitive slaves asylum, and openly offered them protection.” We are told that the Emperor Constantine gave bishops permission to manumit slaves, which would have offered a powerful incentive for conversion to Christianity. St. Gregory, the 4th-century bishop of Nyssa in what is now Turkey, made impassioned arguments against slavery.

Do sheep and oxen beget men for you? Irrational beasts have only one kind of servitude. Do these form a paltry sum for you? ‘He makes grass grow for the cattle and green herbs for the service of men’ [Psalms 103.14]. But once you have freed yourself from servitude and bondage, you desire to have others serve you. ‘I have obtained servants and maidens.’ What value is this, I ask? What merit do you see in their nature? What small worth have you bestowed upon them?

Regrettably, as the Church and Roman state became more tightly allied, politics trumped idealism. In the mid-4th century, Manichaean Christians, who were considered heretics by the Church of Rome, were encouraging slaves to take their freedom into their own hands. The Church convened the Council of Gangra, and issued a formal proclamation aligning with the Roman authorities against the Manichaean slave rebels. “If anyone, on the pretext of religion, teaches another man’s slave to despise his master and to withdraw from his service, and not serve his master with good will and all respect, let him be anathema.”

This became the official Church position for the next 1300 years. Although some writers, including Augustine, voiced opposition, the Vatican repeatedly endorsed slavery from the 5th through 17th centuries. To help enforce priestly celibacy, the 9th Council of Toledo even declared that all children of clergy would be slaves.

Colonial Powers Invoke the Bible; Mennonites and Quakers Raise Opposition

As the countries of Europe colonized the world during the 17th century, the moral authority of Bible and Church offered little protection for subject people in the Americas and Africa. The Dominican Fray Bartolome de las Casas, argued against enslavement of Native Americans, but was ignored. The Catholic Church required only that slaves be non-Christians and captured in a “just war.” Near the close of the 17th century, Catholic theologian Leander invoked both common sense and the Bible in support of Church doctrine:

“It is certainly a matter of faith that this sort of slavery in which a man serves his master as his slave, is altogether lawful. This is proved from Holy Scripture…It is also proved from reason for it is not unreasonable that just as things which are captured in a just war pass into the power and ownership of the victors, so persons captured in war pass into the ownership of the captors… All theologians are unanimous on this.”

Catholic defenders of slavery were not alone. In England, the Anglican Church spent half a century debating whether slaves should taught the core tenets of Christian belief. Opposition came from owners who feared that if slaves became Christians they might be entitled to liberty. In North America Protestants first passed laws requiring that slaves be sold with spouse and/or children to protect the family unit, and then decided that these laws infringed the rights of slaveholders. Many sincere Christians believed that primitive heathens were better off as slaves, which allowed them a chance to replace their demonic tribal lifestyle with civilization and possibly salvation.

But as the 17th century came to a close with broad Protestant and Catholic support for slavery, two minority sects, Mennonites and Quakers began formally converging around an anti-slavery stance. Their opposition to injustice, rooted in their own understanding of the Christian faith, would become the kernel of an abolitionist movement that ultimately leveraged the organizing power and moral authority of Christianity to help end both church and state sanction for human trafficking.

Protestant Support for Slavery Fractures and Turns

The 18th century marked a pivot point in Christian thinking about slavery, much as the 4th century had, but in the opposite direction. At the start of the century, British Quakers forbade slaveholding among their members, and American Quakers even relocated communities from the South to Ohio and Indiana to distance from the practice. But then as now, Quakers were a small sect, the leading edge in their ethical thinking perhaps, but only the leading edge.

It took John Wesley, founder of the Methodist denomination, to bring abolitionism into the Christian main current. A son of the Enlightenment as well as the Christian tradition Wesley drew on both secular and religious tools to make his case. His writings lay out in careful detail the history of the Atlantic slave trade as it was known to him. He cites laws that prescribe mutilation and worse for slaves who offend. He makes the argument in clear secular ethical terms for abolition. He also plumbs the language and passions of faith:

If therefore you have any regard to justice, (to say nothing of mercy, nor of the revealed law of GOD) render unto all their due. Give liberty to whom liberty is due, that is to every child of man, to every partaker of human nature. Let none serve you but by his own act and deed, by his own voluntary choice.–Away with all whips, all chains, all compulsion! Be gentle towards men. And see that you invariably do unto every one, as you would he should do unto you. p. 56

Wesley is keenly aware that the book of Genesis has long been invoked in defense of slavery, and rather than deny the Bible’s dark legacy he invokes it, calling on God himself to free the oppressed from both slavery and sin:

The servile progeny of Ham

Seize as the purchase of thy blood!

Let all the heathen know thy name:

From idols to the living GOD

The dark Americans convert,

And shine in every pagan heart! p. 57

I cite Wesley not because he gets sole or even majority credit for the sea change in Christian thinking during the 18th century, but because he embodies the many currents that came together to create that change. The European Enlightenment prompted lines of ethical philosophy and political analysis that are fundamentally at odds with slave trafficking and forced labor. America’s deist founding fathers documented their own conflicted feelings on the topic. Christians including Puritans, Quakers, Methodists, Anglicans and Baptists wrestled publically with the issue.

The first and second Great Awakenings spawned revival meetings across the country that drew slaves and former slaves into Christianity. And emancipation began making political inroads, though not without opponents. Vermont outlawed slavery in 1777, and by the end of the century, Upper Canada—now Ontario—had implemented a law that would phase out the practice. By contrast, the Catholic Church placed anti-slavery tracts on a list of forbidden books, and Virginia forbade Blacks from gathering after dark, even for worship services.

Christians in the American South Hold Out

By the start of the 19th century, the fight was far from over, but without Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793, legal slavery in Christian-dominant countries might well have ended with a whimper instead of a war. The economic value of slavery was in decline throughout Europe’s empires, and in the American North a transition to grain production had made slavery all but obsolete in some regions. Where slaves cost more to feed than they could produce, owners set them free.

But as cotton production soared in the South, thanks to Whitney’s invention, so did the demand for slave labor. By the start of the Civil War, the South was producing over 4 million bales of cotton annually, up from a few thousand in 1790. Between 1790 and 1808, when an act of Congress banned the Atlantic slave trade, cotton producing states imported 80,000 additional slaves from Africa to meet growing demand.

Northerners could think about slavery in abstract humanitarian terms but for Southerners, slavery was prosperity, and many Southern Christians behaved like owners of oil wells might today: they hunkered down and defended their revenue stream by engaging in the kind of “motivated reasoning” that allows us to find virtue in what benefits us. Under pressure, prominent Christian leaders turn to the Bible to defend the South’s way of life:

Modern Christians Struggle to Disentangle Biblical Authority from Bigotry

On Friday, Dec. 6, 2013, the LDS Mormon Church officially renounced the doctrine that brown skin is a punishment from God. The announcement acknowledged that racism was a part of LDS teaching for generations, as indeed it was, officially, until external pressures including the American civil rights movement and the desire to proselytize in Brazil made segregation impossible. LDS leaders have come a long ways from the thinking of Brigham Young, who wrote, “Shall I tell you the law of God in regard to the African race? If the white man who belongs to the chosen seed mixes his blood with the seed of Cain, the penalty, under the law of God, is death on the spot. This will always be so” (Journal of Discourses, vol. 10).

“This will always be so,” said Young, but modern Mormons believe he was wrong. Similarly, most modern Protestants and Catholics believe their spiritual forefathers were wrong to endorse slavery — or practice it — or preach it from the pulpit. But thanks in part to words penciled by our Iron Age ancestors and decisions made by 4th-century councils, this moral clarity has been painfully difficult to achieve. How much sooner might Christians have come to this understanding if the Church had not treated those ancient words from Genesis and Leviticus and Ephesians as if they were God-breathed?

It is easy to look back on slavery from the vantage of our modern moral consensus—that treating people as property is wrong, regardless of what our ancestors believed. But the very same Bible that provided Furman and Jefferson Davis with a defense of slavery also teaches that nonbelievers are evildoers, women are for breeding, children need beating, and marriage can take almost any form but queer.

This month, aspiring presidential candidate Mike Huckabee was asked to comment on marriage equality and said, “This is not just a political issue. It is a biblical issue. And as a biblical issue, unless I get a new version of the scriptures, it’s really not my place to say, ‘Okay, I’m just going to evolve.’” I’m guessing that the generations of Christians who fought slavery, biblical texts and Church tradition notwithstanding, would beg to differ.

- You may purchase male or female slaves from among the foreigners who live among you. You may also purchase the children of such resident foreigners, including those who have been born in your land. You may treat them as your property, passing them on to your children as a permanent inheritance. You may treat your slaves like this, but the people of Israel, your relatives, must never be treated this way. (Leviticus 25:44-46)

- When a man strikes his male or female slave with a rod so hard that the slave dies under his hand, he shall be punished. If, however, the slave survives for a day or two, he is not to be punished, since the slave is his own property. (Exodus 21:20-21)

- Slaves who have escaped to you from their owners shall not be given back to them. They shall reside with you, in your midst, in any place they choose in any one of your towns, wherever they please; you shall not oppress them. (Deuteronomy 23:15-16)

New Testament Encourages Kindness from Master, Obedience from Slave

Equally regrettable, from the standpoint of moral clarity, is the fact that New Testament writers fail to condemn Old Testament slavery. In fact, the Jesus of Matthew says that he has come not to abolish the Law but to fulfill it: “For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is accomplished” (Matthew 5:18).

Slavery comes up regularly in New Testament texts; but rather than repudiating the practice, the writers simply encourage good behavior on the part of both slaves and masters. Slaves are clearly property of the owners, as are their families. In one parable Jesus compares God to a king who has slaves. When one slave refuses to forgive the debt of a peer, the righteous king treats him in kind, “and, as he could not pay, his lord ordered him to be sold, together with his wife and children and all his possessions, and payment to be made” (Matthew 18:25).

While in prison, the Apostle Paul encounters an escaped slave, Onesimus, and sends a letter to his Christian owner, Philemon, tacitly endorsing Philemon’s authority in the matter. The messages are mixed. Paul sends Onesimus back to Philemon “not as a slave but as a brother”—but he does send him back.

Several letters attributed to Paul express the sentiment that in Christ all people are one:

- For in the one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and we were all made to drink of one Spirit. (1 Corinthians 12:13)

- There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3:28)

- Slaves, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling, in singleness of heart, as you obey Christ; not only while being watched, and in order to please them, but as slaves of Christ, doing the will of God from the heart. Render service with enthusiasm, as to the Lord and not to men and women, knowing that whatever good we do, we will receive the same again from the Lord, whether we are slaves or free. And, masters, do the same to them. Stop threatening them, for you know that both of you have the same Master in heaven, and with him there is no partiality. (Ephesians 6:5-9)

- Let all who are under the yoke of slavery regard their masters as worthy of all honor, so that the name of God and the teaching may not be blasphemed. Those who have believing masters must not be disrespectful to them on the ground that they are members of the church; rather they must serve them all the more, since those who benefit by their service are believers and beloved. (1 Timothy 6:1-3)

Church Fathers Disagree but Pro-Slavery Faction Dominates for 1300 Years

For some early Christians, the message of equality trumped endorsements of slavery. John Fletcher (Lessons on Slavery, 1852) wrote that early sects in Asia Minor “decried the lawfulness of it, denounced slaveholding as a sin, a violation of the law of nature and religion. They gave fugitive slaves asylum, and openly offered them protection.” We are told that the Emperor Constantine gave bishops permission to manumit slaves, which would have offered a powerful incentive for conversion to Christianity. St. Gregory, the 4th-century bishop of Nyssa in what is now Turkey, made impassioned arguments against slavery.

Do sheep and oxen beget men for you? Irrational beasts have only one kind of servitude. Do these form a paltry sum for you? ‘He makes grass grow for the cattle and green herbs for the service of men’ [Psalms 103.14]. But once you have freed yourself from servitude and bondage, you desire to have others serve you. ‘I have obtained servants and maidens.’ What value is this, I ask? What merit do you see in their nature? What small worth have you bestowed upon them?

Regrettably, as the Church and Roman state became more tightly allied, politics trumped idealism. In the mid-4th century, Manichaean Christians, who were considered heretics by the Church of Rome, were encouraging slaves to take their freedom into their own hands. The Church convened the Council of Gangra, and issued a formal proclamation aligning with the Roman authorities against the Manichaean slave rebels. “If anyone, on the pretext of religion, teaches another man’s slave to despise his master and to withdraw from his service, and not serve his master with good will and all respect, let him be anathema.”

This became the official Church position for the next 1300 years. Although some writers, including Augustine, voiced opposition, the Vatican repeatedly endorsed slavery from the 5th through 17th centuries. To help enforce priestly celibacy, the 9th Council of Toledo even declared that all children of clergy would be slaves.

Colonial Powers Invoke the Bible; Mennonites and Quakers Raise Opposition

As the countries of Europe colonized the world during the 17th century, the moral authority of Bible and Church offered little protection for subject people in the Americas and Africa. The Dominican Fray Bartolome de las Casas, argued against enslavement of Native Americans, but was ignored. The Catholic Church required only that slaves be non-Christians and captured in a “just war.” Near the close of the 17th century, Catholic theologian Leander invoked both common sense and the Bible in support of Church doctrine:

“It is certainly a matter of faith that this sort of slavery in which a man serves his master as his slave, is altogether lawful. This is proved from Holy Scripture…It is also proved from reason for it is not unreasonable that just as things which are captured in a just war pass into the power and ownership of the victors, so persons captured in war pass into the ownership of the captors… All theologians are unanimous on this.”

Catholic defenders of slavery were not alone. In England, the Anglican Church spent half a century debating whether slaves should taught the core tenets of Christian belief. Opposition came from owners who feared that if slaves became Christians they might be entitled to liberty. In North America Protestants first passed laws requiring that slaves be sold with spouse and/or children to protect the family unit, and then decided that these laws infringed the rights of slaveholders. Many sincere Christians believed that primitive heathens were better off as slaves, which allowed them a chance to replace their demonic tribal lifestyle with civilization and possibly salvation.

But as the 17th century came to a close with broad Protestant and Catholic support for slavery, two minority sects, Mennonites and Quakers began formally converging around an anti-slavery stance. Their opposition to injustice, rooted in their own understanding of the Christian faith, would become the kernel of an abolitionist movement that ultimately leveraged the organizing power and moral authority of Christianity to help end both church and state sanction for human trafficking.

Protestant Support for Slavery Fractures and Turns

The 18th century marked a pivot point in Christian thinking about slavery, much as the 4th century had, but in the opposite direction. At the start of the century, British Quakers forbade slaveholding among their members, and American Quakers even relocated communities from the South to Ohio and Indiana to distance from the practice. But then as now, Quakers were a small sect, the leading edge in their ethical thinking perhaps, but only the leading edge.

It took John Wesley, founder of the Methodist denomination, to bring abolitionism into the Christian main current. A son of the Enlightenment as well as the Christian tradition Wesley drew on both secular and religious tools to make his case. His writings lay out in careful detail the history of the Atlantic slave trade as it was known to him. He cites laws that prescribe mutilation and worse for slaves who offend. He makes the argument in clear secular ethical terms for abolition. He also plumbs the language and passions of faith:

If therefore you have any regard to justice, (to say nothing of mercy, nor of the revealed law of GOD) render unto all their due. Give liberty to whom liberty is due, that is to every child of man, to every partaker of human nature. Let none serve you but by his own act and deed, by his own voluntary choice.–Away with all whips, all chains, all compulsion! Be gentle towards men. And see that you invariably do unto every one, as you would he should do unto you. p. 56

Wesley is keenly aware that the book of Genesis has long been invoked in defense of slavery, and rather than deny the Bible’s dark legacy he invokes it, calling on God himself to free the oppressed from both slavery and sin:

The servile progeny of Ham

Seize as the purchase of thy blood!

Let all the heathen know thy name:

From idols to the living GOD

The dark Americans convert,

And shine in every pagan heart! p. 57

I cite Wesley not because he gets sole or even majority credit for the sea change in Christian thinking during the 18th century, but because he embodies the many currents that came together to create that change. The European Enlightenment prompted lines of ethical philosophy and political analysis that are fundamentally at odds with slave trafficking and forced labor. America’s deist founding fathers documented their own conflicted feelings on the topic. Christians including Puritans, Quakers, Methodists, Anglicans and Baptists wrestled publically with the issue.

The first and second Great Awakenings spawned revival meetings across the country that drew slaves and former slaves into Christianity. And emancipation began making political inroads, though not without opponents. Vermont outlawed slavery in 1777, and by the end of the century, Upper Canada—now Ontario—had implemented a law that would phase out the practice. By contrast, the Catholic Church placed anti-slavery tracts on a list of forbidden books, and Virginia forbade Blacks from gathering after dark, even for worship services.

Christians in the American South Hold Out

By the start of the 19th century, the fight was far from over, but without Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793, legal slavery in Christian-dominant countries might well have ended with a whimper instead of a war. The economic value of slavery was in decline throughout Europe’s empires, and in the American North a transition to grain production had made slavery all but obsolete in some regions. Where slaves cost more to feed than they could produce, owners set them free.

But as cotton production soared in the South, thanks to Whitney’s invention, so did the demand for slave labor. By the start of the Civil War, the South was producing over 4 million bales of cotton annually, up from a few thousand in 1790. Between 1790 and 1808, when an act of Congress banned the Atlantic slave trade, cotton producing states imported 80,000 additional slaves from Africa to meet growing demand.

Northerners could think about slavery in abstract humanitarian terms but for Southerners, slavery was prosperity, and many Southern Christians behaved like owners of oil wells might today: they hunkered down and defended their revenue stream by engaging in the kind of “motivated reasoning” that allows us to find virtue in what benefits us. Under pressure, prominent Christian leaders turn to the Bible to defend the South’s way of life:

- [Slavery] was established by decree of Almighty God…it is sanctioned in the Bible, in both Testaments, from Genesis to Revelation…it has existed in all ages, has been found among the people of the highest civilization, and in nations of the highest proficiency in the arts. — Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America.

- There is not one verse in the Bible inhibiting slavery, but many regulating it. It is not then, we conclude, immoral. — Rev. Alexander Campbell

- The right of holding slaves is clearly established in the Holy Scriptures, both by precept and example.– Rev. Richard Furman, prominent Baptist and namesake of Furman University

- The doom of Ham has been branded on the form and features of his African descendants. The hand of fate has united his color and destiny. Man cannot separate what God hath joined.—U.S. Senator James Henry Hammond.

Modern Christians Struggle to Disentangle Biblical Authority from Bigotry

On Friday, Dec. 6, 2013, the LDS Mormon Church officially renounced the doctrine that brown skin is a punishment from God. The announcement acknowledged that racism was a part of LDS teaching for generations, as indeed it was, officially, until external pressures including the American civil rights movement and the desire to proselytize in Brazil made segregation impossible. LDS leaders have come a long ways from the thinking of Brigham Young, who wrote, “Shall I tell you the law of God in regard to the African race? If the white man who belongs to the chosen seed mixes his blood with the seed of Cain, the penalty, under the law of God, is death on the spot. This will always be so” (Journal of Discourses, vol. 10).

“This will always be so,” said Young, but modern Mormons believe he was wrong. Similarly, most modern Protestants and Catholics believe their spiritual forefathers were wrong to endorse slavery — or practice it — or preach it from the pulpit. But thanks in part to words penciled by our Iron Age ancestors and decisions made by 4th-century councils, this moral clarity has been painfully difficult to achieve. How much sooner might Christians have come to this understanding if the Church had not treated those ancient words from Genesis and Leviticus and Ephesians as if they were God-breathed?

It is easy to look back on slavery from the vantage of our modern moral consensus—that treating people as property is wrong, regardless of what our ancestors believed. But the very same Bible that provided Furman and Jefferson Davis with a defense of slavery also teaches that nonbelievers are evildoers, women are for breeding, children need beating, and marriage can take almost any form but queer.

This month, aspiring presidential candidate Mike Huckabee was asked to comment on marriage equality and said, “This is not just a political issue. It is a biblical issue. And as a biblical issue, unless I get a new version of the scriptures, it’s really not my place to say, ‘Okay, I’m just going to evolve.’” I’m guessing that the generations of Christians who fought slavery, biblical texts and Church tradition notwithstanding, would beg to differ.

Saturday, February 14, 2015

Magic and Science

-

By Nick Danforth

-

This Is Your Brain on Magic

This Is Your Brain on Magic

Psychologists and neuroscientists have an unlikely ally in

their quest to understand human nature: professional magicians.

She okays. He flips; she glances.

Olson, a graduate student in psychiatry at McGill University, puts the cards back in their box and hands it to her. “So which one did you choose?” The 10 of hearts, she tells him. “The 10 of hearts,” he repeats. “Great. So now if you could just examine the outside of the box to make sure it’s normal”—she does—“and then take that box and just close it right inside your hands.”

He snaps his fingers over hers. “Now I want you to slowly open your hand and read the bar code”—and sure enough, there are the words, printed right on the box: the 10 of hearts. The volunteer hands the box back to Olson, giggling at the seeming impossibility of what just transpired, unaware that she didn’t really choose the 10 of hearts at all. Olson chose it for her, in a piece of trickery so quick and so subtle as to seem almost like magic.

The scene is part of a video released in tandem with Olson’s latest study, published earlier this week in the journal Cognition and Consciousness. Together with a team of researchers from McGill and the University of British Columbia, he demonstrated the effectiveness of a technique that magicians call forcing, or manipulating a person’s decisions without her knowledge.

In the first part of the study, Olson, a practicing magician, approached 118 people and asked them to randomly pick a card as he flipped through the deck, an act that took about a half-second in total. Each time, though, Olson already had a specific card in mind. As he flipped, he’d let his target card show just slightly longer than the rest. Ninety-eight percent of the time, the participants picked the one he had in mind, even as 91 percent said the choice had been entirely theirs—illustrating, the study authors wrote, that magic “can provide new methods to study the feeling of free will.”

But when I asked Olson about the method in question—how, exactly, did he maneuver the flip so that his card showed for just a fraction of a second longer?—he deflected. “I can’t share that,” he said. “It’s part of the secret.”

* * *

Olson and his colleagues are part of a small but growing group of

researchers investigating how tricks like this one can offer insight

into how people think, perceive, and remember. In some ways, the pairing

of science and magic doesn’t seem like much of a pairing at all: One

field dedicated to uncovering the rules of the world, and another

predicated on the (seeming) ability to break them; a discipline that

tries to further understanding, and a performance art whose continued

existence depends on secrecy.In other ways, though, it makes a strange kind of sense. Magicians build their craft on the knowledge of how people act, psychologists dig into the why, and this new area of study that some have dubbed “neuromagic” tries to fill in the space in between. A recent special issue of the journal Frontiers in Psychology titled “The Psychology of Magic, the Magic of Psychology” (Olson was a co-editor) included a study on insight and problem-solving that had subjects watch the same trick over and over until they cracked it, one that used data from eye-tracking movements of audience members to examine attention, and one that used fMRI scans to see what happens in the brain when people witness a seemingly supernatural event.

“The actual link between science and magic is quite intuitive, but it’s actually difficult to draw direct links between the two fields, and one reason is that magicians and scientists generally use quite different language to describe the same principles,” said Gustav Kuhn, a professor of psychology at Goldsmith’s College, University of London, a practicing magician, and another co-author of the Frontiers magic issue.

For example, forcing, the technique examined in Olson’s card study, can take two very different paths towards a similar end. Physical forcing, which Olson used, is when one object is made to somehow stand out over the others that surround it. Psychological forcing, by contrast, is “when you try to make an option more salient in somebody’s mind,” Olson explained. “Say that I ask you to think of a card. Based on the wording of that, I can influence you to choose particular cards.” (In a previous study, he and he colleagues examined the factors that made certain cards more memorable or more visible than others. When the researchers asked subjects to name a card, for example, 40 percent of people would choose either the ace of spades or the queen of hearts, information the team later publicized in the magicians’ magazine Genii.) Both types serve the same purpose—the subject makes what they think is a choice—but one is a matter of perception, the other a more complicated mix of memory, association, and social interaction.

Two other major tenets of magic tricks, illusion and misdirection, present the same sort of challenge. “When [magicians] use misdirection to prevent you from being aware of something, the mechanism by which this happens is sort of irrelevant, really—they just need to have a mechanism that works really well,” Kuhn told me. “But you can fail to notice something because, for example, you fail to encode the information, or because you encode the information and afterwards you forget about it. These are two very different processes in perception and memory, and as scientists, for us, it’s very important to distinguish between the two.”

But if some elements of magic can be translated into patterns and then into science, others are less easily measured, though still easily observed. A trick is not a lab experiment; it’s an inherently social act, one that gets its life from the dynamic between magician and audience. In the second part of Olson’s Cognition and Consciousness study, the researchers tried the same type of physical forcing on a computer, asking volunteers to name a card after seeing several flash by, one staying on the screen imperceptibly longer than the others. The subjects picked the target card 30 percent of the time—still a significant number, but one dramatically smaller than when Olson had been flipping the deck.

“When you give them a choice of card, you want them to make a quick choice and not linger or say, ‘Oh, can I change my card?’ So if a participant is uncomfortable, it’s more likely that they’re going to comply,” Olson explained. But in front of a computer, that discomfort disappears, and with it the tendency to unwittingly succumb to the influence of forcing.

The study of magic, then, is the study of people and groups as much as it is of the senses and the firings of the brain; a magician looks at the whole as much as its parts. “A lot of the demonstrations that I do, when I get inside people’s minds, is understanding human behavior and understanding how people think and getting their patterns down,” famed illusionist Criss Angel told Parade magazine in 2007. “Many people say I’m really a student of humanity.”

* * *

In 1900, Norman Triplett, a professor at Indiana University, published an article in the American Journal of Social Psychology titled “The Psychology of Conjuring Deceptions.”“In the large body of existing conjuring tricks is found much material of value to the psychologist,” he wrote, offering a list that, if not completely comprehensive, must have come close. Over the dozens of pages that followed, he proceeded to group every single act of magic that he knew into categories like “tricks involving scientific principles,” “tricks involving unusual ability, superior information, etc.,” and “tricks depending on a large use of fixed mental habits in the audience.”

Over the next few decades, though, psychologists’ interest in magic petered out, said Ronald Rensink, a professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia whose research on vision has included studies on the illusions used in magic tricks. No one really knows why, he told me, but some argue that it has to do with the rise of behaviorism in the early 20th century. “They were trying to break everything down into simple bits and pieces.” he said. “There’s a bell and you expect meat. Simple associations, simple stimuli, and magic did not fit in to that.”

Another reason, he offered, is that much of magic’s usefulness to science comes from its status as a setup for measurements like eye tracking and fMRI scanning, things that weren’t possible in Triplett’s day. “Keep in mind, they didn’t have the technologies they do today, so they could only go so far.”

Regardless of the cause, magic stayed largely out of the scientific spotlight until 2007, when it became a temporary star. Neuroscientist Susana Martinez-Conde, whose work focused on visual illusions in art, had been appointed a co-chair of the annual meeting for the American Society for the Study of Consciousness, to be held in Las Vegas. She and her co-chair, neuroscientist Steve Macknik, wanted to build the conference around a theme that would pique the interest of those outside the field, she told me. “We were thinking maybe something to do with art.” But on a trip out to Las Vegas to plan the logistics of the weekend, she said, “we’re driving up and down the Strip and we see all of these signs, massive signs of magicians—Penn and Teller, David Copperfield, you name it—and then we realized, just as painters and visual artists have developed all these perceptual illusions, magicians are the cognitive artists.”

The pair asked a group of Las Vegas magicians to come speak at the conference, she said, about “why a specific magic trick of their choice works in the mind of the spectator.” Five of them, including the famously silent Teller of Penn and Teller, accepted the invitation, later collaborating with Martinez-Conde and Macknik on a paper in the journal Nature outlining the scientific lessons to be drawn from various tricks. In a rare moment of transparency, the magicians explained their secrets to the audience at the meeting (the videos are available online)—though after describing Teller’s feat of making coins seemingly materialize in the air, Martinez-Conde, like Olson, declined to explain the mechanics behind the trick. “We’ve gotten in trouble before,” she told me; after the ASSC meeting, she and Macknik joined a handful of magicians’ societies, which require members not to divulge the secrets of the trade.

But those who study magic as a science rather than an art maintain that a knowledge of the nitty-gritty isn’t necessary—magic, though an exclusive circle in some ways, also feeds on the most universal of inclinations.

“We want to explain at a fundamental level why you are so thoroughly vulnerable to sleights of mind,” Martinez-Conde and Macknik wrote in their book Sleights of Mind. “We want you to see how deception is part and parcel of being human. That we deceive each other all the time.”

Friday, February 13, 2015

Elvin T. Lim - The Lovers' Quarrel

The contention is that this country had two foundings. There was 1776 and 1787. The real founding was the adoption of the Constitution, written in 1787. The back and forth between the federalists and the anti-federalists is the background of today's politics according to this author.

The author is a political scientist, which give his narrative a different context than that of the historian.

The author is a political scientist, which give his narrative a different context than that of the historian.

Sunday, February 8, 2015

Gary May - Bending Toward Justice

This book is an account of the enactment of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. It was fun to read as the movie came to town.

No doubt this law transformed American democracy. It completely changed Southern politics for good. Selma's Sheriff Clark was voted out of office in the next election in Selma, and he would never again plague the city with his virulent racism. Voting rights are threatened again today as Republicans do everything they can with ID laws and restrictive hours and limiting absentee voting to reduce access to the ballot.

The Voting Rights Act was signed on August 6, 1965.

The drama of Selma began with a 21 year old man named Bernard Lafayette all of age 21. He deserves as much credit as anyone.

Leadership of the voting rights effort in Selma passed from Lafayette to MLK.

As late as January of 1965 a voting rights bill was not at the top of LBJ's priority list. Events in Selma and the urging of MLK forced his hand, but the President came thru when it counted and when he had the chance to do something. The activist and the politician eventually came together.

There was first talk of a constitutional amendment. Good thing the voting rights bill eventually won out because it would have taken too long for an amendment to go thru the process.

This book puts the times and the enactment of the Voting Rights bill in historical perspective.

No doubt this law transformed American democracy. It completely changed Southern politics for good. Selma's Sheriff Clark was voted out of office in the next election in Selma, and he would never again plague the city with his virulent racism. Voting rights are threatened again today as Republicans do everything they can with ID laws and restrictive hours and limiting absentee voting to reduce access to the ballot.

The Voting Rights Act was signed on August 6, 1965.

The drama of Selma began with a 21 year old man named Bernard Lafayette all of age 21. He deserves as much credit as anyone.

Leadership of the voting rights effort in Selma passed from Lafayette to MLK.

As late as January of 1965 a voting rights bill was not at the top of LBJ's priority list. Events in Selma and the urging of MLK forced his hand, but the President came thru when it counted and when he had the chance to do something. The activist and the politician eventually came together.

There was first talk of a constitutional amendment. Good thing the voting rights bill eventually won out because it would have taken too long for an amendment to go thru the process.

This book puts the times and the enactment of the Voting Rights bill in historical perspective.

Take it Easy on Brian Williams

Let's cut Brian Williams some slack. I told people for years that I was

on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday until some smart aleck

pointed out that I was only 15 at the time and where was my Momma?

Somehow I had convinced myself. . . . oh, nevermind.

Extremism in All Religions

Was Obama right about the Crusades and Islamic extremism? (ANALYSIS)

Obama references crusades, slavery at Prayer Breakfast(5:45)

President

Obama spoke about how religion can be abused and the common theme of

loving thy neighbor during his speech at the National Prayer Breakfast

on Feb. 5, 2015, in Washington, D.C. Here are highlights from that

event.

By Jay Michaelson | Religion News Service February 6

“Humanity has been grappling with these questions throughout human history. And lest we get on our high horse and think this is unique to some other place, remember that during the Crusades and the Inquisition, people committed terrible deeds in the name of Christ. In our home country, slavery and Jim Crow all too often was justified in the name of Christ.”

This would seem to be Religious History 101, but it was nonetheless met with shock and awe.

“Hey, American Christians_Obama just threw you under the bus in order to defend Islam,” wrote shock jock Michael Graham. Rep. Marlin Stutzman, R-Ind., called the comments “dangerously irresponsible.” The Catholic League’s Bill Donohue said: “Obama’s ignorance is astounding and his comparison is pernicious. The Crusades were a defensive Christian reaction against Muslim madmen of the Middle Ages.”

More thoughtfully, Russell Moore, president of the Southern Baptist Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, called Obama’s comments about Christianity “an unfortunate attempt at a wrongheaded moral comparison. ... The evil actions that he mentioned were clearly outside the moral parameters of Christianity itself and were met with overwhelming moral opposition from Christians.”

Really?

1. The Crusades

The Crusades lasted almost 200 years, from 1095 to 1291. The initial spark came from Pope Urban II, who urged Christians to recapture the Holy Land (and especially the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem) from Muslim rule. Like the promise of eternal life given to Muslim martyrs, Crusaders were promised absolution from sin and eternal glory.

Militarily, the Crusades were at first successful, capturing Jerusalem in 1099, but eventually a disaster; Jersualem fell in 1187. Successive Crusades set far more modest goals, but eventually failed to achieve even them. The last Crusader-ruled city in the Holy Land, Acre, fell in 1291.

Along the way, the Crusaders massacred. To take but one example, the Rhineland Massacres of 1096 are remembered to this day as some of the most horrific examples of anti-Semitic violence prior to the Holocaust. (Why go to the Holy Land to fight nonbelievers, many wondered, when they live right among us?) The Jewish communities of Cologne, Speyer, Worms, and Mainz were decimated. There were more than 5,000 victims.

And that was only one example. Tens of thousands of people (both soldiers and civilians) were killed in the conquest of Jerusalem. The Crusaders themselves suffered; historians estimate that only one in 20 survived to even reach the Holy Land. It is estimated that 1.7 million people died in total.

And this is all at a time in which the world population was approximately 300 million — less than 5 percent its current total. Muslim extremists would have to kill 34 million people (Muslim and non-Muslim alike) to equal that death toll today. As horrific as the Islamic State’s brutal reign of terror has been, its death toll is estimated at around 20,000.

2. The Inquisition

While most of us regard “The Inquisition” as a particular event, it actually refers to a set of institutions within the Roman Catholic Church that operated from the mid-13th century until the 19th century. One actually still survives, now known as the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which was directed by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger before his 2005 election as Pope Benedict XVI.

These institutions were charged with prosecuting heresy — and prosecute they did, executing and torturing thousands of suspected witches, converts from Judaism (many of whom had been forced to convert), Protestants, and all manner of suspected heretics, particularly in the 15th and 16th centuries. Historians estimate that 150,000 people were put on trial by the Inquisition, with 3,000 executed.

Arguably, the Islamic State’s methods of execution — including crucifixion, beheading, and, most recently, burning a prisoner alive — are as gruesome as the Inquistion’s, with its infamous hangings and burnings at the stake. ISIS is also committing systematic rape, which the Inquisition did not, and enslaving children.

As for torture, however, it’s hard to do worse than the Inquisition, which used torture as a method of extracting confessions. Methods included starvation, burning victims’ bodies with hot coals, forced overconsumption of water, hanging by straps, thumbscrews, metal pincers, and of course, the rack. Believe it or not, all of this was meant to be for the victim’s own good: better to confess heresy in this life, even under duress, than to be punished for it in the next.

Contrary to Moore’s statement, the Inquisition was not “outside the moral parameters of Christianity itself and ... met with overwhelming moral opposition from Christians.” Though Moore may distinguish between ‘Christianity’ and the Roman Catholic Church, for all intents and purposes the Roman Catholic Church WAS Christianity at the time, or at least claimed to be.

3. Slavery and Jim Crow

“Slaves, obey your masters,” the New Testament says — three times. And indeed, Christian teaching was cited on both sides of the slavery debate, with both slaveholders and abolitionists using it to justify their actions. Segregationists also looked to the “Curse of Ham,” from the story of Noah, and the notion that God had separated the races on different continents. The effects were world-historic in scope: Nearly 12 million people were forced on the “Middle Passage” from Africa to the Americas.

More recently, though the vast majority of Christians abhor it, the Ku Klux Klan, to the present day, still insists that it is a “Christian organization.” There’s a reason the Klan burned crosses alongside its lynchings and acts of arson, after all.

Of course, there was also organized Christian opposition to slavery and to Jim Crow, and Christianity is at least as much the property of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., as of the segregationists and slaveholders of the Old South. But this was precisely Obama’s point: All religions have their hateful extremists, and their prophets of justice.

What about popularity? Do more Muslims support the Islamic State today than Christians supported Jim Crow in the past? No. At the height of the KKK’s popularity in the 1920s, approximately 15 percent of white male Americans were members. That number is eerily similar to the 12 percent of Muslims worldwide who support terrorism today.

In other words, not only is Obama factually correct that Christian extremism across history has been at least as bloody as Muslim extremism today, it is also factually true that such extremisms have been equally popular. True, as Rush Limbaugh points out, the Crusades were “a thousand years ago,” the Inquisition ended 200 years ago, and Jim Crow legally ended in the 1960s. But the president specifically noted that “humanity has been grappling with these questions throughout human history.”

Which is the real point. There are two narratives about radical Islamists, and indeed about enemies of any sort, that coexist in American culture. According to one, they are different from us — Muslims, Palestinians, Israelis, Communists, you name it. Thus, in the battle against Islamic extremism, Islam is, in part at least, the enemy.

The other narrative is that all peoples, all creeds, all nations contain elements of moderation and extremism. Thankfully, racist Christian extremists are today a tiny minority within American Christianity. But only 100 years ago, they were as popular among American Christians as the Islamic State is among Muslims today. Thus, in the battle against Islamic extremism, it is extremism that is the enemy.

Hysterical commentary notwithstanding, no one is suggesting that Christians are just like the Islamic State. But Obama did suggest that Christianity is like Islam; both faiths have the capacity to be exploited by extremists.

Christians should not be insulted by the facts of history. Rather, all of us should be inspired by them to recognize the dangers of extremism — wherever they lie.

Copyright: For copyright information, please check with the distributor of this item, Religion News Service LLC.

Saturday, February 7, 2015

Friday, February 6, 2015

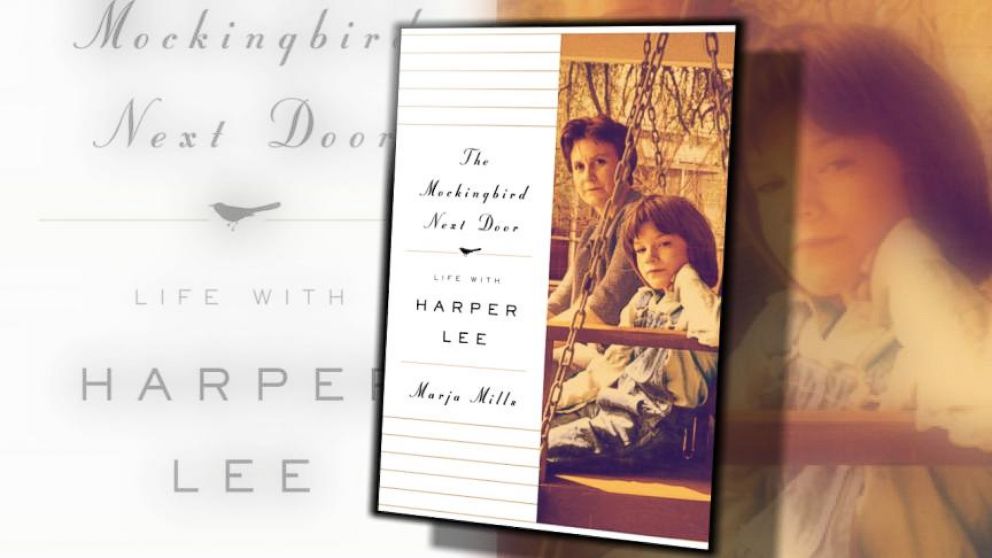

The Talk

About the new Harper Lee novel is fascinating. It will be interesting to watch it all unfold.

Tuesday, February 3, 2015

Amazing

Second Harper Lee Novel to Be Published in July

NEW YORK — Feb 3, 2015, 10:56 AM ET

By HILLEL ITALIE AP National Writer

"To Kill a Mockingbird" will not be Harper Lee's only published book after all.

Publisher Harper announced Tuesday that "Go Set a Watchman," a novel the

Pulitzer Prize-winning author completed in the 1950s and put aside,

will be released July 14. Rediscovered last fall, "Go Set a Watchman" is

essentially a sequel to "To Kill a Mockingbird," although it was

finished earlier. The 304-page book will be Lee's second, and the first

new work in more than 50 years.

The publisher plans a first printing of 2 million copies.

"In the mid-1950s, I completed a novel called 'Go Set a Watchman,'" the

88-year-old Lee said in a statement issued by Harper. "It features the

character known as Scout as an adult woman, and I thought it a pretty

decent effort. My editor, who was taken by the flashbacks to Scout's

childhood, persuaded me to write a novel (what became 'To Kill a

Mockingbird') from the point of view of the young Scout.

"I was a first-time writer, so I did as I was told. I hadn't realized it

(the original book) had survived, so was surprised and delighted when

my dear friend and lawyer Tonja Carter discovered it. After much thought

and hesitation, I shared it with a handful of people I trust and was

pleased to hear that they considered it worthy of publication. I am

humbled and amazed that this will now be published after all these

years."

Financial terms were not disclosed. The deal was negotiated between

Carter and the head of Harper's parent company, Michael Morrison of

HarperCollins Publishers. "Watchman" will be published in the United Kingdom by William Heinemann, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

According to publisher Harper, Carter came upon the manuscript at a

"secure location where it had been affixed to an original typescript of

'To Kill a Mockingbird.'" The new book is set in Lee's famed Maycomb,

Alabama, during the mid-1950s, 20 years after "To Kill a Mockingbird"

and roughly contemporaneous with the time that Lee was writing the

story. The civil rights movement was taking hold by the time she was

working on "Watchman." The Supreme Court had ruled unanimously in 1953

that segregated schools were unconstitutional, and the arrest of Rosa

Parks in 1955 led to the yearlong Montgomery bus boycott.

"Scout (Jean Louise Finch) has returned to Maycomb from New York to

visit her father, Atticus," the publisher's announcement reads. "She is

forced to grapple with issues both personal and political as she tries

to understand her father's attitude toward society, and her own feelings

about the place where she was born and spent her childhood."

Lee herself is a Monroeville, Alabama native who lived in New York in

the 1950s. She now lives in her hometown. According to the publisher,

the book will be released as she first wrote it, with no revisions.

"To Kill a Mockingbird" is among the most beloved novels in history,

with worldwide sales topping 40 million copies. It was released on July

11, 1960, won the Pulitzer Prize and was adapted into a 1962 movie of the same name, starring Gregory Peck

in an Oscar-winning performance as the courageous attorney Atticus

Finch. Although occasionally banned over the years because of its

language and racial themes, the novel has become a standard for reading

clubs and middle schools and high schools. The absence of a second book

from Lee only seemed to enhance the appeal of "Mockingbird."

Sunday, February 1, 2015

Thomas C. Foster - Twenty-Five Books That Shaped America

You can argue with the 25 books that this critic chose, but you can't argue with his wit and presentation. This is fun reading!

The sun never sets on Hemingway. The author makes the most out of his simple words in The Sun Also Rises just as Hemingway makes the most out of a sparse story. At the same time, the author perhaps stretches things when he says there would have been no Raymond Carver with his famous minimalist prose. How do we know there would have been no Carver without Hemingway?

I have read so many things about the symbols in The Great Gatsby I don't know what to say. My hunch is that your guess is as good as mine on the green light and the ashes.

The author makes some sense of Faulkner's Go Down, Moses, but I doubt I will ever attempt it.

I'm glad I read Moby Dick in college. I could never go thru it again. Let the whiteness of the whale and what the whale symbolizes rest.

I'm glad this Yankee included To Kill a Mockingbird. Perhaps there's hope for some Yankees.

This is a fun book.

The sun never sets on Hemingway. The author makes the most out of his simple words in The Sun Also Rises just as Hemingway makes the most out of a sparse story. At the same time, the author perhaps stretches things when he says there would have been no Raymond Carver with his famous minimalist prose. How do we know there would have been no Carver without Hemingway?

I have read so many things about the symbols in The Great Gatsby I don't know what to say. My hunch is that your guess is as good as mine on the green light and the ashes.

The author makes some sense of Faulkner's Go Down, Moses, but I doubt I will ever attempt it.

I'm glad I read Moby Dick in college. I could never go thru it again. Let the whiteness of the whale and what the whale symbolizes rest.

I'm glad this Yankee included To Kill a Mockingbird. Perhaps there's hope for some Yankees.

This is a fun book.

Super Bowl

It's

a good thing I don't care about the Super Bowl. Who cares who wins?

Who's playing anyway? The outcome will not improve my digestion or make

my dreams any sweeter. Not caring about this game is one less stress

point in my life. I don't like chicken wings. I don't like guacamole.

I don't like watching football in groups. Guess I'm out of luck today.

P.S. Go Seattle. Beat New England!

P.S. Go Seattle. Beat New England!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)